Triage Protocols and Operational Challenges in Large-Scale Military Disasters and Chemical/Biological Warfare Scenarios

Large-scale military disaster or a chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear (CBRN) attack requires a doctrinal shift from conventional patient-centered care Triage, in this context, transcends a simple classification tool; it becomes a mechanism for maximizing aggregate survivability.

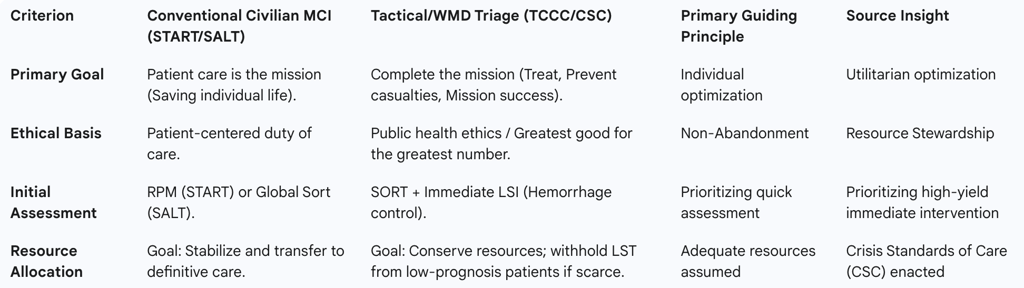

The effective medical response to a large-scale military disaster or a chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear (CBRN) attack requires a doctrinal shift from conventional patient-centered care to a utilitarian model of resource stewardship governed by Crisis Standards of Care (CSC). Triage, in this context, transcends a simple classification tool; it becomes a mechanism for maximizing aggregate survivability, preserving fighting strength, and ensuring mission accomplishment. This report analyzes the adaptation of conventional triage systems for high-threat environments, details the necessary agent-specific modifications for CBRN incidents, and explores the profound operational, logistical, and ethical challenges inherent in large-scale casualty management.

Doctrinal Foundations: The Paradigm Shift from Civilian to Tactical Triage

The foundation of mass casualty incident (MCI) management is the rapid and systematic prioritization of victims to optimize the use of finite medical resources. However, the application of triage protocols in a high-threat or military setting fundamentally alters the underlying objectives, necessitating adaptive and hybrid methodologies.

The Tactical Imperative: Redefining the Mission in Military Triage

In the standard civilian environment, the guiding principle is that the patient is the mission, meaning all resources are dedicated primarily to achieving the best possible outcome for the individual patient. In contrast, combat situations, high-threat scenarios, and large-scale military disasters require a nuanced approach where the patient’s welfare is viewed in the context of broader operational success. The Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) and similar military and tactical frameworks accomplish three main goals in descending order of priority: (1) Treat the casualty; (2) Prevent further casualties; and (3) Complete the mission.

This mission-centric calculus compels medical planners to utilize triage explicitly as a resource allocation tool designed to maximize combat effectiveness and minimize personnel diversion. If the primary objective is mission completion, the deployment of limited specialized assets, such as Role 1 or Role 2 medical staff, surgical teams, or blood products, must prioritize those casualties who have a high probability of survival and a rapid return to duty, or those requiring high-yield damage control surgery. Allocating scarce resources to casualties triaged as EXPECTANT—those whose injuries are unlikely to be survivable given the environment and resource constraints—would compromise the care available for those designated IMMEDIATE or DELAYED. Therefore, triage in the tactical setting becomes a force multiplier, designed to conserve operational momentum and maintain the integrity of the force. The utilitarian calculation inherent in this structure must be formalized in doctrine and training to manage the inherent tension with traditional medical ethics.

Conventional Triage Systems (START, SALT, RAMP) and Baseline Utility

Standardized algorithmic systems provide a repeatable and rapid method for sorting casualties in the initial phase of an MCI, regardless of the incident etiology.

The Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (START) system remains the most widely used in the United States. START relies on a quick assessment of Respirations, Perfusion, and Mental Status (RPM) to categorize patients. For example, a casualty who is walking is immediately classified as MINOR (Green). A patient who cannot walk, has a respiratory rate greater than 30, or cannot follow simple commands is immediately categorized as IMMEDIATE (Red). While simple and effective for initial blast or trauma scenarios , START's primary limitation in the tactical or CBRN context is its lack of emphasis on immediate, pre-tagging intervention.

The Sort, Assess, Lifesaving Interventions, Treatment/Transport (SALT) system was developed as a national all-hazards standard to address the need for early high-impact interventions. SALT begins with a global sorting process, instructing patients who can walk to move to a designated area, classifying them as the last priority for individual assessment. Crucially, SALT mandates immediate Lifesaving Interventions (LSI) before completing the full assessment and tagging. These interventions include controlling major hemorrhage, typically through tourniquets or direct pressure, and opening the airway using positioning or basic adjuncts.

The critical operational advantage of SALT's LSI incorporation is evident in high-threat or blast injury contexts. Military experience and analyses of civilian mass shootings have shown that rapid control of extremity hemorrhage is a life-saving, high-yield intervention. In a dynamic environment, the few seconds required to apply a tourniquet saves more lives than a perfectly executed diagnostic algorithm that delays intervention. The RAMP system similarly provides a quick assessment based on the ability to follow commands and the presence of a palpable radial pulse for delayed categorization. For WMD response planning, the integration of immediate LSI validates SALT as a preferred, robust baseline standard, upon which specific agent-based modifications can be layered.

Integrating Triage into Tactical Frameworks (TCCC/TECC)

Triage protocols in high-threat environments must shift flexibly between formalized algorithmic models, such as START or SALT, and rapid, heuristic-based assessments to manage the chaotic and dynamic challenges posed by terrorist attacks or active threat scenarios. Tactical frameworks, including TCCC and TECC, prioritize rapid, trauma-focused interventions (often summarized by the MARCH algorithm: Massive hemorrhage, Airway, Respirations, Circulation, Head injury/Hypothermia) within operational phases: Care Under Fire, Tactical Field Care, and Tactical Evacuation Care.

Hybrid models, integrating the reliability of algorithmic approaches with the speed and situational adaptability of heuristic decision-making, offer the most balanced solution for these complex environments. This blending allows responders to quickly utilize the triage system (e.g., START/SALT) to sort large numbers while maintaining the operational focus and immediate life-saving priorities of TCCC/TECC. Triage decisions made in Role 1 (field care) are documented on a TCCC Card, reflecting the immediate focus on hemorrhage control and airway management, before transitioning to the more comprehensive ABCDE (Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure) method and formalized documentation at Role 2 facilities.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Triage Paradigms in WMD Context

The Utilitarian Mandate: Triage Modification for Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear (CBRN) Events

CBRN mass casualty scenarios introduce unique challenges related to contamination, rapid clinical deterioration, and the necessity for specific, often scarce, pharmacological countermeasures. These factors necessitate a radical departure from conventional triage practices.

WMD Triage Principle: Crisis Standards of Care (CSC) Implementation

In CBRN incidents, the scale of casualties often rapidly exceeds the capacity of the medical system, leading to sustained resource shortfalls that require the implementation of Crisis Standards of Care (CSC). The overwhelming magnitude of the situation compels decision-makers to modify conventional treatment priorities. Triage, under these circumstances, must be executed using priorities designed to provide the greatest benefit for the largest number of patients without wasting specialist skill and medical resources.

This approach formalizes utilitarian ethics within the protocol. When critical resources, such as ventilators, antidotes, or highly specialized personnel, become scarce, clinicians must apply legally and ethically complex criteria to allocate them. The protocol must explicitly define the transition points between Contingency (functionally equivalent care) and Crisis (care resulting in poor outcomes for individuals) levels of care. This definition must detail when patients who would typically receive IMMEDIATE care, based on their clinical status, must be downgraded to DELAYED or EXPECTANT solely due to the lack of available resources needed for prolonged intervention. The explicit codification of these criteria ensures transparency and consistency in decision-making, which is crucial for reducing the moral distress experienced by providers.

Agent-Specific Triage Modifications: Chemical Warfare

Chemical warfare agents pose distinct clinical challenges that require immediate recognition and specialized pharmacological intervention, directly influencing triage categorization.

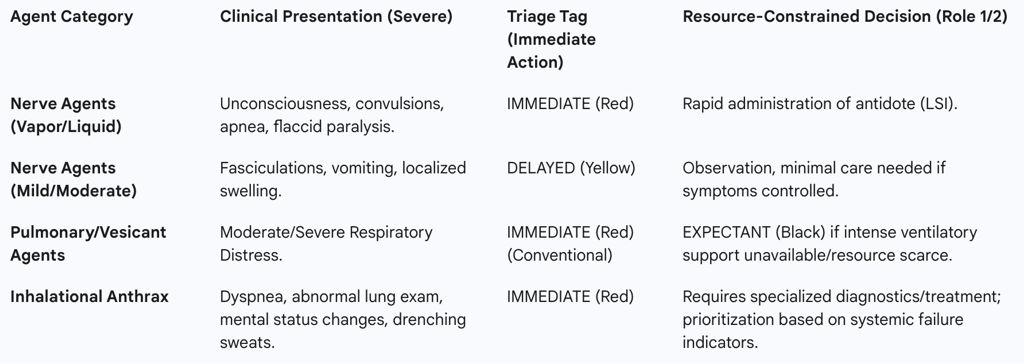

Nerve Agents (Sarin, VX): Nerve agents act rapidly, with vapor exposure effects manifesting within seconds to minutes. Triage must quickly differentiate symptom severity to prioritize antidote administration.

Severe Symptoms categorize patients as IMMEDIATE (Red). These include unconsciousness, convulsions, apnea, and flaccid paralysis. These patients require immediate airway support and antidote administration (e.g., atropine and pralidoxime).

Mild/Moderate Symptoms typically result in a DELAYED (Yellow) categorization. These include localized swelling, muscle fasciculations, nausea and vomiting, weakness, and shortness of breath.

The Unexposed: Patients who are conscious and retain full muscular control, especially those with a history of possible vapor-only exposure who show no signs upon reaching the medical facility, have not been effectively exposed and require minimal care (MINOR tag).

Vesicant and Pulmonary Agents (Phosgene, Mustard): Triage for agents causing acute respiratory distress is highly susceptible to resource scarcity. Casualties with moderate or severe respiratory distress caused by phosgene or vesicant agents would conventionally be classified as IMMEDIATE, requiring intense ventilatory support. However, this classification is dependent on the immediate availability of sustained, high-level respiratory support.

In forward-deployed facilities, such as Role 1 or unit-level Medical Treatment Facilities (MTF), these systems may not be immediately available or sustainable for the hours required to stabilize and transport the casualty to a larger facility. In such austere environments, limited medical assets are conserved for those more likely to benefit. Consequently, the triage classification for severe respiratory failure in these cases must transition to EXPECTANT (Black) due to the limited capacity of the system, a definitive example of applying the utilitarian calculus mandated under CSC.

Agent-Specific Triage Modifications: Biological Warfare

Biological agents introduce complexity due to incubation periods, potential for delayed onset, and the risk of person-to-person transmissibility, which overlays an epidemiological concern onto the clinical assessment.

Inhalational Anthrax: Triage algorithms for bio-agents rely on the clinical manifestation of symptoms that can mimic common illnesses, making specialized checklists vital. Key criteria include fever, chills or cough, dyspnea, nausea or vomiting, abnormal lung examination, severe headache, mental status changes, and drenching sweats. Patients presenting with these systemic signs of infection, particularly dyspnea or mental status deterioration, require IMMEDIATE categorization for antibiotic therapy and supportive care.

Transmissible Agents (e.g., Smallpox): The planning for transmissible biological agents must account for their potential to spread rapidly after the initial attack, requiring isolation and epidemiological triage alongside injury assessment. This dual requirement demands that triage officers possess expertise not only in trauma and clinical signs but also in infectious disease management and quarantine protocols.

Table 2: Triage Decision Matrix for Specific Chemical Agents

Operational and Logistical Friction: The Decontamination and Evacuation Nexus

The most significant operational challenges during a CBRN mass casualty event are not clinical but logistical, primarily centering on mitigating contamination and managing high patient volume under restrictive safety protocols.

The Decontamination Imperative and Secondary Exposure Risk

Effective triage cannot safely commence until patient contamination has been fully mitigated. The 1995 Tokyo Sarin attack provided a critical lesson regarding the necessity of decontamination protocols. In that incident, 135 Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs) and 23% of the medical staff at St. Luke’s hospital were secondarily affected because contamination was not adequately addressed. Had the agent been deployed at a higher concentration, secondary exposure would likely have been fatal to medical responders. The risk of contaminating higher echelons of care (Role 2/3) is particularly acute for severely injured victims who have experienced higher agent exposure levels.

The priority at the scene is the immediate stripping of contaminated clothing, which provides little protection and often absorbs and holds chemical agents against the skin. Immediate clothing removal, without concern for the order or process of removal, must precede skin washing. For litter-bound patients arriving at the decontamination site (often Phase 2), team members must swiftly cut off all clothes, rolling the patient as necessary to complete the process before moving them to the washing station.

The Impact of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) on Triage Performance

The mandatory use of specialized Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), such as Mission-Oriented Protective Posture (MOPP) gear, severely constrains the speed, duration, and fidelity of the triage assessment.

The time personnel can remain safely in PPE performing physically demanding tasks like triage or decontamination is limited by the level of protection, ambient weather conditions, and the physiological response of the staff to stress. Teams must consistently monitor fellow members for signs of heat stress or physical problems, sometimes identified simply by observing their eyes within the mask. This limited "clean time" inside PPE becomes a critical resource itself, demanding that triage protocols be maximally streamlined.

The reduced manual dexterity and sensory input while wearing heavy PPE decrease the accuracy of detailed physiological assessments, such as precisely counting respiratory rates or locating faint radial pulses, which are central to START/SALT algorithms. This operational constraint reinforces the reliance on simplified, rapid indicators and hybrid triage models. The physical limitations imposed by PPE inherently justify the utilitarian triage modification wherein prolonged intervention for high-acuity patients is deemed infeasible, thereby validating the Expectant categorization of resource-intensive casualties. Training must, therefore, incorporate realistic PPE drills focused on rapid communication and maximizing patient throughput under strict, physiologically determined time limits.

Echelons of Care and Patient Evacuation Dynamics (The Flow State)

Effective management of a CBRN MCI requires establishing a continuous, multi-phased patient flow system that utilizes repeated triage across successive Echelons of Care.

Military Echelons: Medical care progresses from Role 1 (unit-level aid, TCCC/MARCH focus) to Role 2 (advanced trauma management, limited surgical capability, 72-hour hold capacity, transition to ABCDE) , and onward to Role 3, 4, and 5 facilities that provide specialized and definitive care.

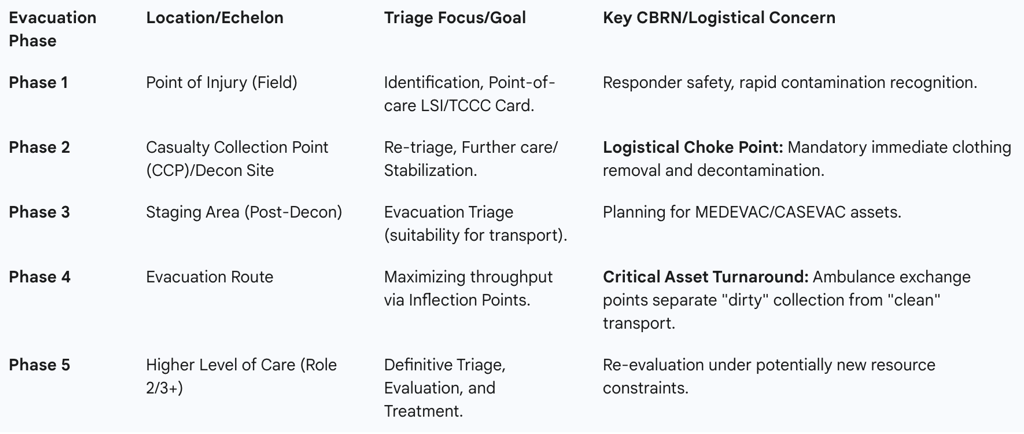

Phases of Patient Movement and Repeat Triage: Triage is a dynamic process that requires re-evaluation at multiple inflection points.

Phase 1 (Field): Initial identification and point-of-care treatment (e.g., hemorrhage control) occurs.

Phase 2 (CCP): Casualties arrive at the Casualty Collection Point (often synchronized with the Decontamination site) for initial triage and further care. CCPs are often temporary and require rapid transfer planning.

Phase 3 (Evacuation Triage): Patients are re-triaged to assess suitability for evacuation to a higher echelon, initiating the utilization of medical evacuation (MEDEVAC) assets.

Phase 4 (Inflection Points): This critical stage involves using strategic exchange points and asset release triggers to maximize logistical throughput and asset turnaround times.

Phase 5 (Destination Triage): Patients undergo final triage upon arrival at a higher level of care (Role 2/3) for definitive evaluation and treatment.

The implementation of Phase 4 logistics is essential for overcoming the logistical barriers posed by contamination. If transport assets must wait for full decontamination and processing before returning to the scene, the entire system will suffer throughput failure. Inflection Points, such as Ambulance Exchange Points, are designed to separate the "dirty" collection phase from the "clean" transport phase. For instance, a "dirty" ambulance can drop off decontaminated patients at a designated exchange point, immediately transferring them to a waiting "clean" evacuation asset, thereby allowing the contaminated vehicle to return to the pickup point faster. This strategy, mandatory for sustaining high-volume operations in a protracted WMD scenario, ensures that resource limitations do not prematurely halt casualty evacuation.

Table 3: WMD Patient Flow and Logistical Inflection Points

Governance, Ethics, and Preparedness: Sustaining the Moral and Legal Framework

The move to Crisis Standards of Care (CSC) in WMD events represents a profound ethical shift that must be managed through robust governance, clear policy, and comprehensive provider support to ensure legality and transparency.

Mandates for Ethical Triage and Crisis Standards of Care (CSC)

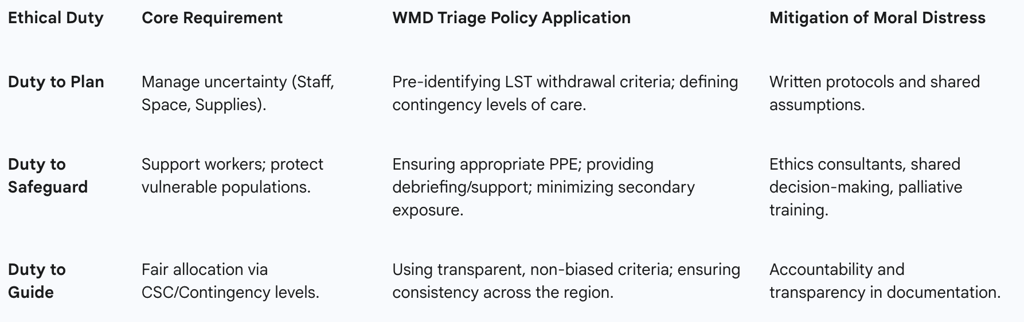

Healthcare institutions, and by extension, military medical command structures, have an explicit duty to ensure that decision-making under CSC is fair, ethical, legal, transparent, and compassionate. This obligation is defined by three core ethical duties for healthcare leaders responding to a crisis affecting operations :

Duty to Plan: Leaders must manage inherent uncertainties regarding staff, space, and supplies. Planning includes identifying potential triage decisions related to the initiation or withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment (LST) and defining clear contingency levels of care.

Duty to Safeguard: This involves supporting the workforce, recognizing their heightened risk of occupational harm during a surge event (especially in high-level PPE), and protecting vulnerable populations. It mandates providing immediate support and ensuring measures are taken to mitigate secondary exposure risk.

Duty to Guide: This duty requires using transparent CSC guidelines to ensure the fair allocation of scarce resources. Allocation decisions must be guided by core values, including fairness, the duty to care without bias, the duty to steward resources (the greatest good for the greatest number), transparency, consistency, proportionality, and accountability. It is strictly prohibited to consider non-medical factors such as age, disability, race, gender, or subjective quality of life judgments in triage decisions.

Mitigating Moral Distress and Ensuring Accountability

The requirement for clinicians to operate under a utilitarian model, potentially necessitating the withholding of life-sustaining treatment from salvageable patients due to resource limits, generates significant moral distress. Leaders must proactively establish mechanisms to mitigate this psychological toll.

The burden of making life-or-death resource allocation decisions should never rest on a single clinician. Institutions must maintain ready availability of ethics consultants and interdisciplinary triage teams to share the responsibility and ensure decision consistency. Furthermore, providing regular debriefing and support for all clinicians is essential for addressing the moral anguish associated with operating under crisis protocols.

Even when resources are critically limited, the institution must maintain policies for respectful care for the deceased. Logistically, this requires moving deceased casualties (Black Tag/Expired/Unsalvageable) to a designated site that is not easily observed by living casualties or the public. They must remain segregated, undergoing thorough decontamination, until law enforcement evidence collection is complete and the living patients have been evacuated. Palliative interventions for end-of-life care must be actively incorporated into crisis response plans, along with specialized palliative care education for clinicians forced into unfamiliar roles.

Training and Readiness (Simulations and Lessons Learned)

The complexity of WMD triage—combining mass trauma assessment, agent recognition, contamination management, and CSC implementation—requires advanced training beyond standard MCI protocols. After-Action Reviews (AAR) from military exercises often reveal that units lack the specific subject matter expertise (SME) to properly manage the medical triage and the overflow of injured civilians or non-combatants in complex disaster scenarios.

Training must integrate the technical demands of chemical exposure, including PPE usage, positive pressure ventilation (PPV), decontamination procedures, and recognizing specific chemical agent information. Effective preparation should utilize tools such as virtual reality (VR)-based scenarios and traditional disaster management simulations. These simulations are invaluable for team training, assessment, and accurately gathering lessons learned necessary for corrective actions during the AAR process. This commitment to sophisticated training is vital to bridge the gap between abstract doctrine and practical application, ensuring that triage officers can confidently implement agent-specific modifications (e.g., differentiating severe nerve agent symptoms versus simple trauma) and execute resource-based CSC decisions.

Table 4: Ethical Duties and Policy Requirements for Crisis Standards of Care

Conclusions and Recommendations

The triage of casualties in large-scale military disasters, particularly those involving WMD agents, demands a structured, hybrid approach that explicitly balances clinical efficacy with operational necessity. The analysis demonstrates that effective triage is achieved by moving beyond simple assessment algorithms (START) to methodologies that incorporate immediate lifesaving interventions (SALT LSI) and, critically, by adopting the utilitarian principles formalized under Crisis Standards of Care (CSC).

Doctrinal Formalization of Utilitarian Triage: Triage protocols for WMD events must formally adopt CSC principles, explicitly defining the point at which resource scarcity mandates the downgrade of patients who would otherwise be IMMEDIATE to EXPECTANT. This modification is particularly critical for pulmonary and vesicant agent exposures in austere forward echelons where prolonged ventilatory support is unavailable. The strategic deployment of medical resources must prioritize aggregate survival and mission continuation.

Logistical Prioritization of Asset Turnaround: The primary logistical barrier is the decontamination and clearance process. Strategic planning must mandate the establishment of Casualty Collection Points (CCPs) as primary logistical exchange points. The implementation of Phase 4 Inflection Points, specifically ambulance exchange points, is mandatory to separate "dirty" collection from "clean" transport, maximizing the turnaround speed of evacuation assets and preventing systemic flow failure.

Mandatory Specialized Training and Ethical Governance: Command structures must invest in advanced simulation training (including VR and AARs) to address the identified expertise gap in CBRN medical management and patient overflow. Furthermore, to mitigate provider moral distress and ensure legal adherence, leadership must uphold the three ethical duties (Plan, Safeguard, Guide) by establishing shared decision-making frameworks, ensuring full transparency in resource allocation criteria, and integrating palliative and end-of-life care into crisis response plans.