The Mexican Emergency Triage Imperative

he effective management of medical emergencies constitutes a foundational requirement for any national health system committed to patient safety and resource optimization. In Mexico, the deployment of emergency triage systems is a critical response mechanism designed to navigate the systemic constraints inherent in a segmented public health infrastructure.

The effective management of medical emergencies constitutes a foundational requirement for any national health system committed to patient safety and resource optimization. In Mexico, the deployment of emergency triage systems is a critical response mechanism designed to navigate the systemic constraints inherent in a segmented public health infrastructure. Triage systems are fundamentally implemented to deliver a medical response based specifically on the severity of a patient's condition, with the primary objectives being to save the maximum number of lives, ensure the optimal allocation of available resources, facilitate timely and accurate diagnosis, and ultimately optimize the time required for comprehensive attention.

The Policy Mandate: Triage as a Pillar of Emergency Care Quality

Federal institutions such as the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) articulate that the implementation of a robust Triage service reinforces core policy principles, including detecting aspects that may alter a patient's prognosis and maintaining an institutional "zero rejection" policy. The successful adoption of Triage, coupled with efficient patient transfer protocols, is intended to expedite treatment delivery and improve overall timeliness. This mandate underscores the crucial role of Triage not merely as a clinical tool but as a strategic element in institutional logistics and governance.

Defining Fragmentation: The Regulatory-Institutional Divide

Despite the national mandate to utilize classification protocols, the core challenge confronting the Mexican healthcare system is the structural fragmentation of Triage application. This fragmentation is characterized by a conspicuous lack of uniformity and systematization across major federal institutions, including IMSS, the Institute for Social Security and Services for State Workers (ISSSTE), and the Secretariats of Health (SSA) at the state level.

The resulting divergence means that implementation is highly variable and often falls into "empirical Triage models," particularly in facilities dealing with elective medical-surgical emergencies. The systematization process, therefore, relies heavily on the local experience of the personnel applying quality improvements rather than adherence to a unified, nationally validated framework. When these divergent systems are applied outside of the limited geographic area where they may have been initially validated, the variability of the outcomes increases significantly, challenging the establishment of dependable referral networks and standardization.

The Consequence of the 'Zero Rejection' Paradox

The public commitment to a policy of "cero rechazos" necessitates that emergency departments possess a highly effective, rapid, and reliable triage system capable of managing high patient inflows efficiently. However, when the underlying Triage mechanism is compromised by fragmentation, low reliability, and the use of unvalidated empirical models, the "zero rejection" policy paradoxically increases the operational burden on the inadequate internal processes.

If patients cannot be classified accurately or quickly due to institutional divergence, the capacity to rapidly diagnose and treat critical cases is diminished, regardless of the institutional commitment to not deny entry. Consequently, the fragmentation of Triage acts as a critical choke point, risking delayed care for the most acute patients and potentially compromising the institutional goal of optimizing patient prognosis. The failure to standardize Triage processes translates directly into operational strain and reduced safety margins across the National Health System (SNS).

The Regulatory Baseline: NOM-027-SSA3-2013 and the Gaps in Mandate

The legal and operational foundation for emergency services in Mexico is established by the Norma Oficial Mexicana (NOM), specifically NOM-027-SSA3-2013, which regulates the functioning and attention criteria for emergency services in medical care establishments. An analysis of this regulatory framework reveals both the strengths of mandated infrastructure and personnel requirements, and the critical weaknesses that permit fragmentation.

Scope and Obligatoriness of the Standard

NOM-027-SSA3-2013 is binding across the entire health spectrum: it is of mandatory observance for all establishments and the professional and technical personnel within the public, social, and private sectors that provide emergency medical care. Importantly, the scope of this NOM excludes mobile units, such as ambulances. The objective of the standard is to define minimum characteristics, including physical infrastructure (e.g., dedicated areas for stretchers, reception and control modules, assessment cubicles, a shock room, and an observation area) and organizational criteria for service functioning. Furthermore, the emergency department is required to provide medical care 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

Personnel Requirements and the Initial Assessment Mandate

To ensure continuous coverage, the NOM requires that emergency services must have, permanently available, at least one physician and one nursing element to immediately attend to any patient requiring care. The regulation places specific emphasis on the assessment process: medical personnel providing care are explicitly required to "determine the patients' needs for attention based on classification protocols of priorities for medical emergencies". Upon patient reception, a physician is legally required to assess the patient and establish the priorities of attention. The physician responsible for the emergency department must also establish and supervise administrative controls and ensure that updated documents, including clinical practice guides for emergency care, are applied.

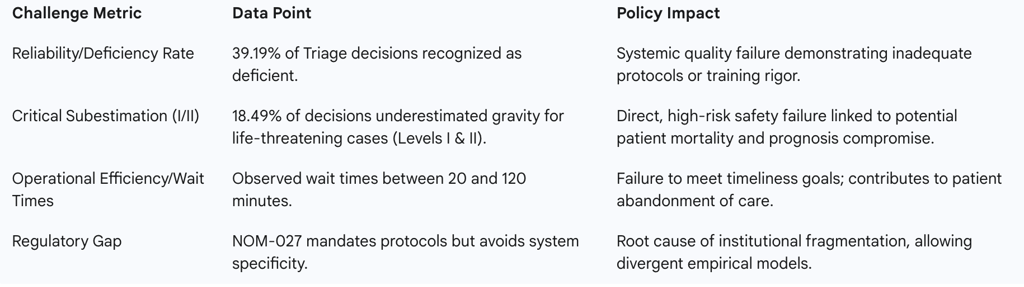

The Critical Policy Lacuna: Mandating Protocols but Avoiding Specifying a Model

While NOM-027-SSA3-2013 successfully mandates the necessary infrastructure and requires the use of priority classification protocols, it critically fails to establish a singular, nationally binding Triage system or scale. This lack of specificity is the root regulatory failing that has institutionalized fragmentation. The standard's ambiguity—requiring a doctor to "assess and establish the priorities" but not dictating how that assessment must be classified—allows institutions the legal latitude to implement their own divergent, often empirical, Triage models.

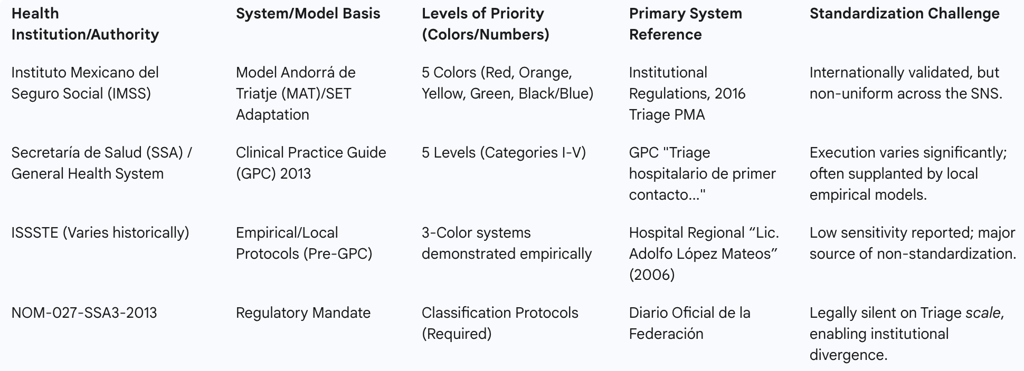

This regulatory omission created a vacuum in which institutions like IMSS developed regulations based on international models (such as the Andorran Triage Model), independent of the national Clinical Practice Guide (GPC) issued by the Secretariat of Health, thus ensuring that uniformity could not be achieved through regulatory compliance alone.

Systemic Implications of Regulatory Emphasis

The regulatory emphasis that dictates a physician must assess and establish patient priorities upon reception potentially creates two downstream systemic challenges. First, it may unintentionally delay the Triage process during high-volume periods, as physicians are often required for higher-level diagnostic or therapeutic tasks, creating a bottleneck at the entry point. Second, this requirement is often in tension with validated international Triage methodologies, which frequently demonstrate that the initial Triage application can be executed with adequate reliability and efficiency by highly trained nursing staff. Restricting the Triage authority exclusively to physicians, as interpreted from the NOM, limits the efficient deployment of the available nursing workforce, even though the standard mandates the permanent presence of both a doctor and a nurse.

Furthermore, the legal exclusion of mobile ambulance units from NOM-027-SSA3-2013 —with pre-hospital care governed separately by NOM-034-SSA3-2013 —creates an inherent disconnect in the continuum of care. The absence of mandatory concordance between the pre-hospital and hospital Triage scales (e.g., using START/MASS in the field versus a 5-level scale in the hospital) leads to potential misclassification and friction during patient transfer, impacting the seamless transition necessary for critical trauma and medical cases.

Deep Dive into Institutional Models and Technical Specifications

The operational reality of emergency triage in Mexico is defined by the coexistence of incompatible technical models, primarily centered on a division between internationally recognized 5-level scales and varied, often low-sensitivity, 3-color scales.

The IMSS Model (Andorran/SET Adaptation): The 5-Level Standard

The IMSS, the largest social security institution, has adopted a structured and standardized Triage system based on the Model Andorrá de Triatje (MAT), which itself is an adaptation of the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS). This framework is often recognized in Spanish literature as the Sistema Español de Triage (SET). This model operates using a five-level classification scale, often utilizing five distinct colors (typically Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, and Black/Blue) to denote urgency and establish strict maximum waiting times for initial medical contact. IMSS actively promotes public awareness campaigns to ensure patients understand this 5-color classification system upon seeking emergency services.

The institutional adoption of the MAT/SET adaptation provides IMSS with an internationally validated methodology that has demonstrated greater utility compared to simpler three- or four-color systems. The 5-level structure provides finer discrimination of urgency, minimizing the aggregation of clinically heterogeneous patients into overly broad categories like "Yellow." In 2009, IMSS further institutionalized its classification by implementing "Emergency Networks," designed to streamline patient flow and referral between primary and secondary care units based entirely on its 5-level Triage system.

SSA and ISSSTE Models: Empirical and Variational Implementation

The efforts by the federal Secretariat of Health (SSA) to unify the system have met with limited success due to institutional autonomy and implementation variability. The SSA’s Centro Nacional de Excelencia Tecnológica published the Clinical Practice Guide (GPC) "Hospital Triage of First Contact in Adult Emergency Services for Second and Third Level" in 2013, with the goal of establishing a common five-level priority scale across the National Health System. However, the report highlights that a substantial portion of these recommendations relies solely on expert opinion rather than rigorous clinical validation.

The ISSSTE, another large federal social security provider, has exhibited variability in its Triage implementation. While aiming to classify patients by clinical state to identify the most severe , an earlier experience reported by the Hospital Regional “Lic. Adolfo López Mateos” in 2006 utilized an empirically performed three-color classification protocol, demonstrating a relatively low sensitivity of only 60.2%. This suggests that despite the SSA’s push for a GPC-based 5-level standard, operational units within the SSA and ISSSTE systems have historically relied on simpler, less reliable, and empirically derived Triage systems.

This high variability creates significant operational friction. A patient presenting with a moderate, non-life-threatening condition might be classified as 'Green' (Level 4, requiring potential delayed consultation) in a state SSA hospital, while the same clinical presentation might place them in the 'Yellow' (Level 3, requiring priority attention) category in a nearby IMSS facility using the MAT scale. Such classification dissonance compromises regional referral and transfer agreements, undermining the overall effectiveness of the segmented health system.

Specialized Triage Contexts

The Triage mechanism has proven adaptable to specialized medical fields, further illustrating its core utility. A prominent example is the adaptation for Obstetric Triage, which is specifically designed for use during the perinatal period (pregnancy, labor, and puerperium). This specialized system aims to promptly identify obstetric emergencies, triggering the activation of the critical maternal surveillance route, known as "Code Mother," to minimize maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality. While clinically crucial, the necessity of specialized triage models highlights the importance of ensuring they are interoperable and consistent with the general emergency department scale, facilitating swift transition between triage assessment and definitive care.

A conceptual overview of the institutional fragmentation is presented in the following table:

Table 1: Comparison of Major Federal Institutional Triage Systems in Mexico (Conceptual)

Clinical and Operational Outcomes of System Fragmentation

The fragmentation of Triage is not merely an administrative inconvenience; it translates directly into quantifiable deficiencies in patient safety and systemic efficiency. The use of non-standardized and often empirical Triage models has resulted in documented failures in reliability, leading to high rates of misclassification that jeopardize patient outcomes and waste critical institutional resources.

Reliability and Validation Failures: The Risk of Critical Subestimation

Academic meta-analyses reflecting the reliability of Triage protocols utilized in some emergency settings have exposed alarming failure rates. Data indicates that Triage protocol decisions resulted in 39.19% being recognized as deficient. This high deficiency rate is symptomatic of a failure to standardize training, ensure inter-observer reliability, and utilize clinically validated protocols.

Of greater concern for patient safety is the documented rate of critical subestimation. In this specific meta-analysis context, 18.49% of the decisions critically underestimated the severity of the patient's condition, corresponding specifically to life-threatening categories, Levels I and II. The clinical implication is severe: nearly one-fifth of the classification failures place patients with time-sensitive, potentially lethal conditions at risk due to delayed or inadequate initial response. The reliance on non-validated, often empirical Triage models that lack the diagnostic discrimination of internationally accepted 5-level systems is a direct contributor to this unacceptable safety metric.

Resource Misallocation and the Efficiency Paradox

Conversely, the fragmentation also leads to system over-utilization, demonstrating a lack of precision in the classification process. It was observed that 20.7% of Triage decisions over-estimated the patient’s severity. While less dangerous than subestimation, this overestimation directly results in the misallocation of high-value resources, such as specialized personnel, shock room availability, and immediate diagnostics, toward patients whose conditions do not warrant such immediate critical intervention. This diversion of resources is unsustainable and degrades the capacity of the department to respond effectively when a truly Level I emergency arrives.

This operational inefficiency manifests clearly in patient wait times. Observational data reveals highly variable and extensive waiting periods, ranging from 20 minutes to 120 minutes. A two-hour maximum wait time for an initial assessment severely violates the principle of timely care that Triage is designed to uphold. Such systemic delay forces emergency departments to operate constantly under strain, leading to bottlenecks. Furthermore, low efficiency particularly impacts patients classified in lower-priority categories, such as Green or Blue, whose prolonged waits can lead to frustration, premature abandonment of care, or clinical deterioration, subsequently increasing the demand on follow-up consultation services.

The Operational Cost of Low Reliability

The high metrics for both critical subestimation and overestimation indicate that fragmented, low-reliability models create an operational dependency on the receiving physician to re-triage or override the initial classification. While the NOM-027 mandates that a physician must assess priorities upon reception , the low confidence in the preceding classification necessitates this clinical verification. This mandatory re-evaluation slows down the entire flow of care, negating the time-saving benefits of the Triage process and contributing to the extended wait times observed. The system, therefore, pays an operational cost for its low reliability by increasing the workload burden on specialized medical personnel at the intake module.

Triage Fragmentation as a Symptom of Systemic Underinvestment

The persistence of non-standardized Triage models is fundamentally linked to broader systemic challenges beyond mere clinical oversight. The adoption of validated, internationally endorsed Triage systems requires significant investment in standardized training, electronic algorithms, and specialized supplies. Analysts have pointed out that the failure to adopt these established systems is often attributed to institutional constraints, including "non-flexible regulations" and, crucially, a lack of funding for the required investment.

The resulting fragmentation is thus a structural symptom of the fragmented, segmented, and unequally resourced nature of the public health system. Disparities in investment capacity among the various subsytems (IMSS, ISSSTE, state SSA entities) ensure that a unified, high-reliability Triage system cannot be sustained nationally without a fundamental reallocation of resources and legislative enforcement of standards.

Table 2: Documented Operational Failures and Policy Implications

Global Models and the Path to Standardization in Mexico

Addressing the deep-seated fragmentation requires leveraging globally validated methodologies and implementing high-level policy mechanisms to override institutional barriers. The international landscape provides clear direction, and recent domestic legislative action demonstrates political will to mandate standardization.

Evaluation of International 5-Level Systems

The international scientific community strongly advocates for the adoption of uniform, valid, and standardized Triage scales to demonstrably improve the quality and safety of patient care. Systems based on 5-color scales, such as the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS), the Spanish Triage System (SET), or the Andorran Model (MAT), are recognized for offering superior utility and clinical discrimination compared to 3- or 4-color systems.

The existing institutional framework within Mexico already contains the foundation for national standardization. The IMSS's strategic decision to adopt an adaptation of the MAT/SET model provides a readily available and internationally accepted template. Although its implementation must be adapted to local specificities, promoting this 5-level, algorithm-based framework across the entire National Health System represents the most pragmatic pathway to achieving high reliability and acceptable inter- and intra-observer agreement.

Policy Initiatives for Unification: Legislative Momentum

The failure of the technical regulatory framework (NOM-027) and the Clinical Practice Guide to achieve national standardization has led to the elevation of the Triage issue to the legislative sphere. This escalation confirms that technical governance alone cannot resolve the fragmentation caused by the structural segmentation of the Mexican health system.

In 2024, a legislative initiative was presented to the Chamber of Deputies proposing the addition of a specific mandate for a Triage system into Article 6° of the General Health Law. The exposition of motives supporting this initiative explicitly addresses the core problem: the public health system is segmented and fragmented, leading to vast differences in financing, quality, coverage, and the resulting models of care. The fragmentation is cited as a cause of inadequate coordination and lack of continuity in attention times, validating the observed deficiencies in process and outcomes. By seeking to mandate Triage standardization through the fundamental General Health Law, legislators are acknowledging that only a statutory requirement can compel compliance and integration across autonomous institutions like IMSS, ISSSTE, and SSA.

The Role of the Nursing Profession in Triage Modernization

Optimizing efficiency and reducing the excessive wait times documented in current empirical models requires a strategic adjustment in personnel utilization. International evidence strongly supports the adequate applicability and high reliability of Triage scales when executed by appropriately trained nursing staff.

Leveraging the nursing workforce for the initial classification assessment would maximize efficiency and resolve the bottleneck created by relying on the physician for initial assessment at the point of reception, a practice implied by the current interpretation of NOM-027. By formally authorizing and training nurses to function as expert Triage officers, the health system can align its operational practices with global best standards, simultaneously adhering to the NOM-027 requirement for a nurse to be permanently available to immediately attend to patients.

Strategic Recommendations for National Triage Coherence

Based on the analysis of regulatory shortcomings, institutional divergence, and critical safety metrics, the following strategic recommendations are proposed to establish national Triage coherence, improving patient safety and system efficiency across the Mexican National Health System.

Recommendation 1: Legislative and Regulatory Amendment

To overcome institutional autonomy and enforce true national standardization, the Triage mandate must be elevated to a statutory level, closing the regulatory lacuna left by NOM-027-SSA3-2013.

Enact Statutory Mandate: The Legislative Branch should proceed with the proposed amendment to the General Health Law, mandating the universal implementation of a single, nationally validated, five-level Triage scale across all public and social health entities.

Revise NOM-027-SSA3-2013: The Secretariat of Health must revise the existing NOM to explicitly specify the adoption of the unified scale (e.g., standardizing the IMSS-utilized MAT/SET variant across all SSA and ISSSTE units). This regulatory update must detail the clinical criteria, key discriminants, and algorithmic structure of the unified system, ensuring a consistent application language nationwide.

Recommendation 2: Institutional Alignment and Training Reengineering

A unified scale requires a unified approach to personnel competence and deployment to guarantee reliability.

Develop National Training and Certification: A single national Triage training curriculum and certification program must be developed and applied to all professional personnel. This program must emphasize inter-institutional reliability testing (inter-observer validation) to reduce the high rates of deficient decisions and critical subestimation documented in current practice.

Formalize Nursing Triage Authority: Institutional regulations must be formally revised to authorize and train nursing personnel to execute the initial Triage assessment. This strategic deployment maximizes efficiency, reduces physician burden at the intake module, and aligns operational practices with global best practices.

Recommendation 3: Quality Control, Auditing, and Performance Benchmarks

Operational effectiveness must be continuously monitored against objective, publicly reported metrics to drive continuous improvement.

Establish National Key Performance Indicators (KPIs): The health authorities must establish mandatory national KPIs for Triage performance. These indicators must include maximum acceptable wait times for each of the five color classifications (e.g., Level 3/Yellow must receive initial medical contact within a defined threshold, ideally aligning with or improving upon existing institutional targets such as the informal 30 minutes or less target for initial contact ).

Mandatory Reliability Auditing: Implement mandatory national audits designed to track and publish institutional rates of overestimation and critical subestimation (Levels I/II). By leveraging the metrics already identified in clinical literature (the 18.49% subestimation rate), continuous accountability can be enforced, compelling institutions to invest in better training and resources to mitigate patient safety risks.