The Global Landscape of Pediatric Emergency Triage Systems

The establishment of dedicated Pediatric Emergency Triage Systems (PETS) is rooted in the fundamental clinical principle that children are not merely reduced-size adults. Significant physiological and anatomical differences necessitate distinct triage criteria and acuity scales to accurately assess and manage pediatric illness and injury.

The establishment of dedicated Pediatric Emergency Triage Systems (PETS) is rooted in the fundamental clinical principle that children are not merely reduced-size adults. Significant physiological and anatomical differences necessitate distinct triage criteria and acuity scales to accurately assess and manage pediatric illness and injury. Failure to recognize these divergences can lead to critical errors in acuity assignment, resulting in dangerous treatment delays or inappropriate resource allocation.

One of the most critical aspects of pediatric specificity involves fundamental physiological responses to stress and illness. A child’s cardiovascular system, for instance, responds uniquely to events like bleeding or shock. Unlike adults, whose blood pressure often drops early in shock, children maintain their blood pressure longer through powerful compensatory mechanisms, often masking severe underlying circulatory compromise until decompensation is imminent. Consequently, medical staff cannot reliably apply adult vital sign criteria—including blood pressure, pulse rate, respiration rate, and temperature—when evaluating a child. Dedicated, age-stratified criteria are essential to identify the subtle signs of deterioration before overt collapse occurs.

Furthermore, anatomical variances dictate differences in trauma patterns and physiological vulnerability. Smaller children, for example, possess a significantly larger head-to-body ratio, affecting injury patterns and increasing susceptibility to head trauma. Pediatric bone structure is also more flexible, meaning that fractured bones may cause a greater systemic impact on a child’s body than they would on an adult's body. Triage systems must therefore incorporate dedicated algorithms that account for these unique injury mechanisms. This reinforces the principle that age must function as the primary modifier overlay for any PETS. If a system employs fixed vital sign cutoffs developed primarily for adults or older children, it will systematically fail to capture the subtle, high-risk changes indicative of severe illness in infants, confirming the need for highly granular, age-stratified criteria embedded directly into the decision matrices.

Historical Shift to Standardized Five-Level Triage

Globally, emergency medicine has shifted toward highly sensitive five-level triage instruments to enhance patient safety and minimize the risk of mortality associated with delays in treatment. These instruments stratify patients into five acuity categories, ranging from immediate resuscitation (Level 1) to non-urgent care (Level 5). The five-level approach offers greater discriminatory power compared to older three- or four-level systems, allowing for more precise allocation of increasingly constrained emergency department (ED) resources.

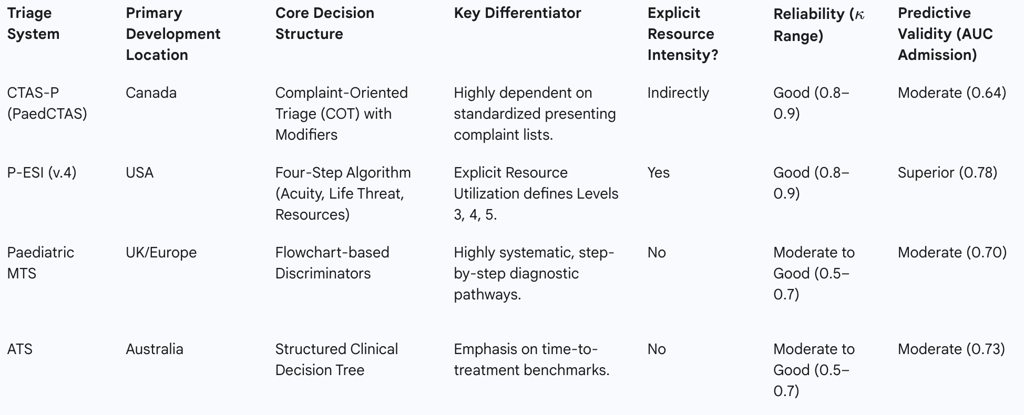

The leading internationally recognized five-level pediatric triage instruments include the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS-P), the Manchester Triage System (MTS), the Emergency Severity Index (ESI), and the Australasian Triage Scale (ATS). While these systems share the five-level structure, they utilize distinct algorithms and decision rules, leading to variability in performance across different populations and clinical settings.

The complexity inherent in achieving accurate, highly detailed five-level stratification demands significant structural support. Systems like CTAS are described as structurally simple but "content rich". The sheer volume of clinical presentation modifiers and complex physiological cutoffs required to triage the broad scope of ED presentations—from major trauma to diffuse pediatric presentations—poses a significant challenge for healthcare providers. Consequently, relying solely on a nurse's memory or simplified reference tools is unsustainable. The experience gained since five-level triage was implemented has consistently demonstrated the need for computerized decision support to assist nurses at the point of care. The reliability and accuracy of CTAS level assignment, for instance, are directly contingent upon comprehensive training and technological aids, suggesting that triage accuracy is not purely a function of the algorithm's design but is significantly mediated by implementation factors and the fidelity of training. This imperative for technological assistance must be considered when comparing data across different sites, as the method of score assignment—whether by computer decision support, paper reference, or memory—may influence the reported accuracy and reliability metrics.

Comparative Analysis of Leading International Five-Level PETS

Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale – Pediatric (CTAS-P / PaedCTAS)

The Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale, applied for pediatrics (PaedCTAS), is one of the most widely validated and utilized five-level PETS internationally. It is fundamentally a Complaint-Oriented Triage (COT) system. Its structure links standardized presenting complaints to specific clinical modifiers—such as the presence of severe pain, level of hemorrhage, or degree of respiratory distress—to assign an acuity score.

CTAS has demonstrated robust inter-rater reliability, with validation studies reporting Kappa values ranging from 0.8 to 0.9. This indicates that different triage nurses using the system tend to assign the same acuity level with high consistency, which is a vital indicator of system robustness and standardized application. However, CTAS’s predictive validity for final disposition, such as hospital admission, has been reported as moderate in some comparative studies (Area Under the Curve, or AUC, of 0.64).

The operational effectiveness of CTAS is heavily reliant on systematic training and access to standardized reference materials. To manage the complexity of its guidelines, CTAS is designed to be highly conducive to computerization, providing nurses with real-time decision support. Policy implications derived from CTAS experience dictate that when comparing CTAS data across different clinical sites, it is crucial to specify whether scores were assigned using computer decision support, paper-based reference materials, or solely by memory, as these factors significantly influence the reported accuracy and reliability of the assigned acuity levels.

Emergency Severity Index – Pediatric (P-ESI)

The Emergency Severity Index (ESI) is a unique five-level triage algorithm that separates patients into acuity groups based on a combination of acuity and expected resource needs. The ESI algorithm begins by assessing high-acuity criteria (Decision Points A and B): immediate life threats, hemodynamic instability, or high-risk vital signs, which assign the patient to Level 1 (Resuscitation) or Level 2 (Emergent). P-ESI explicitly recognizes that children have different physiological and psychological responses to stressors than adults, necessitating pediatric-specific guidance in its application.

The critical difference in the ESI framework lies in the assignment of intermediate and low-acuity patients (Levels 3, 4, and 5). Once high-acuity criteria are ruled out, the triage nurse determines the expected resource intensity required for the patient's workup. Level 3 patients are anticipated to require multiple resources (e.g., laboratory tests, X-ray imaging, complex procedures); Level 4 patients require only a single resource (e.g., consultation with one specialist, simple dressing); and Level 5 patients require only a history and physical exam.

P-ESI consistently demonstrates high inter-rater reliability, comparable to CTAS (Kappa 0.8–0.9). Furthermore, ESI exhibited superior predictive ability for hospital admission in comparative studies, showing an AUC of 0.78 (95% CI 0.74–0.81), indicating its effectiveness in distinguishing between low and high urgency patients and reducing the overall risk of undertriage compared to systems like MTS. The high predictive power for admission inherent in ESI is directly attributable to its explicit incorporation of resource utilization. Because hospitalization frequently necessitates an extensive diagnostic workup involving multiple resources, measuring expected resource use intrinsically correlates with the eventual need for admission (the common validation gold standard). This makes ESI exceptionally effective as a predictive tool for ED throughput management and operational efficiency. However, this reliance on resource intensity presents a challenge regarding universal adoption: what defines "multiple resources" in a sophisticated, high-volume North American ED may be an impossible standard in a resource-scarce environment, requiring substantial contextual adaptation for transferability.

Manchester Triage System – Pediatric (Paediatric MTS)

The Manchester Triage System (MTS) is widely used across Europe and beyond. It employs a system of flowcharts and a structured list of predefined clinical discriminators to guide the nurse through five urgency levels. It is primarily a clinically driven system focused on time-to-treatment benchmarks.

Validation studies have generally assigned moderate to good performance to MTS. It has been shown to have moderate to good inter-rater reliability (Kappa 0.5–0.7) and moderate predictive validity for admission (AUC 0.70). While effective, the MTS has a noted tendency toward overtriage compared to other systems.

A more critical concern surrounding MTS is the risk of undertriage, which, although infrequent (reported at 0.9% in one study), can be clinically severe. Analysis shows that undertriage is significantly more likely in high-risk groups: specifically infants, especially those under three months of age, and children whose complaint routed them through the 'unwell child' flowchart. The risk of undertriage stems from the underlying dynamic that younger children rely heavily on objective physiological parameters (Vital Parameters, VPs) rather than subjective symptoms or communication ability for an accurate assessment. If the triage algorithm relies too heavily on subjective symptoms or requires communication cues, the subtle but critical physiological signs of impending collapse in infants may be missed, leading to unwarranted delays in care. To mitigate this documented flaw, recommendations strongly advocate for systematic assessment of vital signs in all pediatric patients, regardless of initial perceived severity, ensuring objective physiological data overrides subjective assessment. Efforts to modify MTS have focused on introducing new, age-optimized discriminators for children under one year to improve its sensitivity to high-urgency patients.

Australasian Triage Scale (ATS)

The Australasian Triage Scale (ATS) is another well-established five-level system, structurally comparable to CTAS and MTS, emphasizing timely treatment. It demonstrated moderate to good inter-rater reliability in comparative studies (Kappa 0.5–0.7). In terms of predictive validity for admission, the ATS showed an AUC of 0.73; however, it was characterized by very low sensitivity (13%) but high specificity (94%). This profile suggests that while the ATS is highly accurate in identifying patients who will not be admitted (high specificity), it fails to capture a significant proportion of patients who ultimately require hospitalization (low sensitivity), potentially classifying these admitted patients at lower acuity levels than required.

Table 1: Comparative Structure and Performance of Leading Five-Level Pediatric Triage Systems

Validation and Performance Metrics of PETS

Inter-Rater Reliability and Reproducibility

Inter-rater reliability is a crucial metric, defining the consistency and reproducibility of triage assignments regardless of the individual nurse performing the assessment. High reliability ensures that the system maintains internal consistency, which is fundamental for regulatory compliance, maintaining appropriate patient flow, and accurate data reporting.4 The metric commonly used for this assessment is the quadratic-weighted Kappa ($\kappa$).

Comparative systematic reviews demonstrate a clear distinction in reliability performance. Both the ESI and CTAS consistently exhibit superior inter-rater reliability, with Kappa values typically falling in the range of 0.8 to 0.9.5 This high level of agreement suggests that the decision points within these algorithms are structurally clear and less prone to subjective interpretation. Conversely, MTS and ATS show reliability values described as moderate to good, with Kappa scores generally ranging between 0.5 and 0.7.5

The differences in reliability are not solely algorithmic; they are often a function of implementation protocols. The high reliability observed in systems that are complex but designed for computer support, such as CTAS, underscores a significant operational principle: sophisticated triage protocols require rigorous execution methods to maintain accuracy.4 The degree of triage accuracy and reliability is highly dependent on implementation factors, specifically comprehensive training and consistent access to technological decision support or standardized reference materials.

Predictive Validity Against Clinical Outcomes

Predictive validity assesses the efficacy of a triage score in correctly forecasting severe clinical outcomes, such as the need for hospitalization, admission to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU), or increased length of stay.9 The Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) is the standard metric for comparing the predictive efficacy of these systems.

Based on published comparative research, the P-ESI demonstrated the highest predictive validity for hospital admission, yielding an AUC of 0.78.5 The ATS followed with an AUC of 0.73, and the MTS achieved an AUC of 0.70.5 CTAS, while highly reliable, showed a slightly lower predictive AUC of 0.64.5

The superior predictive power of the ESI model warrants deeper examination. ESI’s success in predicting high-urgency patients and reducing undertriage compared to MTS and NTS is fundamentally tied to its structure, which incorporates expected resource utilization as a decision point for lower-acuity patients.6 This architectural choice means the system not only measures clinical acuity but also assesses the complexity of the medical evaluation required. Therefore, ESI optimizes ED flow and efficiency by stratifying patients based on required resources, making it a highly effective tool for resource management and ED throughput.6 Policy analysts must critically distinguish whether the primary institutional goal is operational efficiency (favoring ESI) or maximizing immediate physiological risk sensitivity (favoring clinical scales or hybrid models).

The Scandinavian Rapid Emergency Triage and Treatment System-pediatric (RETTS-p) has also been subjected to validation studies. These analyses corroborated RETTS-p's validity by demonstrating a strong dose-response relationship between increasingly high priority ratings and indicators of severe disease, including hospitalization to the wards, longer hospital stays, and referral to the PICU.15 For these proxy variables, high priority ratings were significantly associated with adverse outcomes compared to low priority ratings, confirming that the system accurately mirrors medical urgency across a broad spectrum of pediatric conditions.15

The Universal Challenge of Undertriage and Overtriage

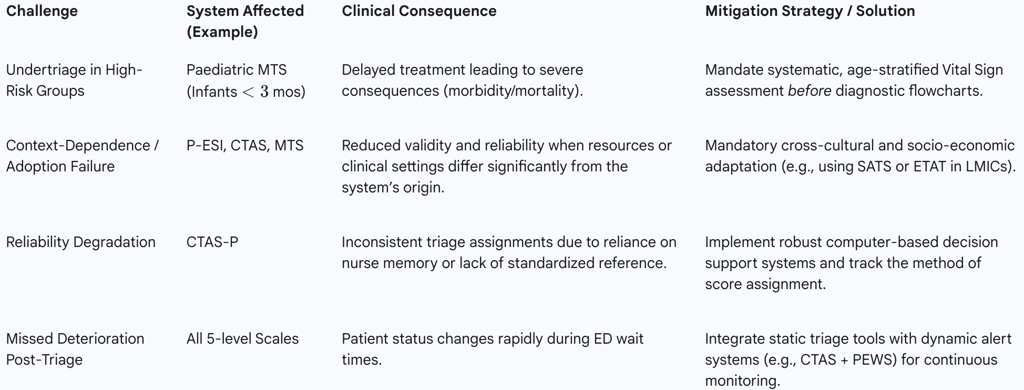

A pervasive challenge across all standardized PETS is the potential for triage error, manifesting as either undertriage or overtriage.

Undertriage occurs when a patient who is critically ill or requires hospitalization or intensive intervention is assigned an inappropriately low urgency level (typically Levels 3, 4, or 5). Systematic reviews confirm that patients at the lowest urgency levels are occasionally admitted to the hospital, reflecting missed severity.9 The consequence of undertriage is treatment delay, which can lead to increased use of diagnostics and interventions, longer hospitalization, complications, morbidity, and, in severe cases, mortality.13

A recurrent and high-risk demographic susceptible to undertriage are infants, particularly those under three months of age, who are often routed through the 'unwell child' flowchart in systems like the MTS.13 This vulnerability is amplified because younger children rely almost entirely on non-verbal cues and physiological parameters (VPs) for an accurate assessment of status.14 If the triage model relies on the patient's capacity for communication or subjective history, the subtle clinical manifestations of deterioration in infants—who are often compensating effectively until sudden collapse—will be overlooked.13 This inherent vulnerability in the very young mandates that any refined PETS must prioritize objective vital parameter assessment and include dedicated, highly sensitive decision pathways for non-verbal populations to prevent severe clinical consequences.

Overtriage occurs when a low-acuity patient is assigned an unnecessarily high urgency level (Level 1 or 2). While overtly less dangerous than undertriage, overtriage burdens limited ED resources, potentially delaying care for truly emergent patients, and contributes to ED overcrowding. The MTS, for example, has been noted to have a moderate tendency towards overtriage in pediatric emergency care.11 Efforts to reduce both types of errors remain central to the ongoing refinement of all major international triage systems.

Integrated and Regional Specialized Systems

Scandinavian Model: Rapid Emergency Triage and Treatment System-pediatric (RETTS-p)

The Scandinavian Rapid Emergency Triage and Treatment System-pediatric (RETTS-p) represents a sophisticated, hybrid model widely adopted in Nordic countries, including use in pre-hospital emergency medical services (EMS) and most pediatric emergency departments (PEDs).15

RETTS-p operates as a five-level priority system that utilizes a systematic, two-pronged assessment approach to ensure comprehensive evaluation 19:

Vital Signs (VS): Based on the universally accepted ABCDE framework (Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure), which includes specific measurements for heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, temperature, and oxygen saturation.

Emergency Symptoms and Signs (ESS): A structured set of clinical findings derived from flowcharts based on the patient's presenting complaint and history.

The system’s assignment logic dictates that the patient is assigned the highest medical risk level derived from either the VS assessment or the ESS assessment.19 This structure ensures that a child presenting with normal vital signs but a highly concerning symptom (e.g., severe hemorrhage) is appropriately prioritized, while a child with subtle, unstable vital signs but a vague chief complaint (e.g., general lethargy) is also accurately flagged as high-risk.

RETTS-p has demonstrated substantial inter-rater reliability, with scores comparable to CTAS and MTS in validation studies.14 Furthermore, its validity has been established by showing a clear dose-response relationship between higher triage codes and proxy indicators of severe disease, such as hospitalization and referral to the PICU.15 Prior to its introduction in 2012, all nurses underwent comprehensive theoretical and practical training, highlighting the critical role of standardized education in maintaining system reliability.21

Auxiliary Pediatric Alert Systems (POPS, PEWS, PAT)

In addition to static, five-level initial triage tools, supplementary systems exist primarily for the dynamic monitoring and early recognition of clinical deterioration. These include the Pediatric Early Warning Score (PEWS), the Pediatric Observation Priority Score (POPS), and the Pediatric Approach Triangle (PAT).3 These are often color-stratified alert systems designed to complement—not replace—the initial triage assessment.

The primary role of these alert systems is to enhance the safety net for pediatric patients after their initial triage assignment, particularly during the often lengthy waiting period in the ED or upon admission.22 However, studies have demonstrated that PEWS alone is inadequate as a sole initial triage screening tool, showing poor sensitivity (32% to 44%) in predicting significant illness or hospital admission.23 This limited utility for initial triage stems from the fact that alert scores are typically narrow physiological scoring systems designed for dynamic tracking, failing to capture the comprehensive history and symptomology necessary for effective initial resource and acuity stratification.

Optimal clinical practice therefore mandates a layered approach: initial static triage (e.g., using CTAS or ESI) to prioritize queue order and resource needs, followed immediately by continuous, dynamic monitoring using an alert system (e.g., PEWS or POPS).22 Combining systems, such as using PEWS alongside CTAS, has been shown to enhance the ability to identify early signs of deterioration, providing a comprehensive strategy that addresses both instantaneous prioritization and subsequent clinical decline.22

Global Health Model: WHO Emergency Triage Assessment and Treatment (ETAT)

The Emergency Triage Assessment and Treatment (ETAT) guidelines, developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), represent a fundamental approach tailored for resource-constrained settings, where pediatric mortality within 24 hours of admission remains a significant threat.24

The ETAT framework is distinct from resource-intensive Western models. It focuses on the rapid, systematic identification and treatment of immediate life-threatening conditions (emergency signs).24 These high-priority conditions include, but are not limited to, severe dehydration, circulatory impairment or shock, airway obstruction, breathing problems, and severely altered central nervous system function (coma or convulsive seizures).24 ETAT serves as a highly practical, simplified triage tool designed to prevent death through urgent appropriate care.24 In regions with limited staff specialization and scarce resources, such as those often found in low- to middle-income countries (LMICs), ETAT provides a clinically focused, high-impact triage methodology that is far more viable than complex systems like P-ESI, which rely on the availability of standardized laboratory and imaging resources.10

Implementation Challenges and Policy Implications

The Necessity of Cross-Cultural and Socio-Economic Adaptation

A critical finding in the research literature is that the predictive validity and overall performance of standardized PETS are strongest within their countries of origin or in neighboring regions with similar healthcare infrastructure.17 The adoption of these leading systems internationally requires complex cross-cultural adaptation rather than mere linguistic translation.17

The adaptation barrier is particularly pronounced in Low- to Middle-Income Countries (LMICs). These settings often face immense challenges that compromise the effectiveness of resource-dependent Western models, including scarcity of resources, difficulty processing a high volume of patients quickly, and the absence of dedicated, trained emergency medicine teams.10 In many tertiary care settings in LMICs, pediatric emergencies are managed by pediatric residents who are also responsible for non-emergency conditions, further complicating the implementation of resource-intensive algorithms.10 Given these limitations, local healthcare organizations often find it necessary to implement or adapt simplified triage tools, such as the South African Triage Scale (SATS), or rely on the WHO ETAT guidelines, which align better with resource limitations and staffing structures.10

Non-Clinical Factors in Triage: Expanding the Scope

Effective pediatric triage extends beyond the measurement of vital signs and physical symptoms to encompass significant non-clinical factors, particularly concerning mental and behavioral health (MBH) and patient diversity.25

The triage and management of acute MBH emergencies in children and youth necessitate a systematic approach. This includes understanding potential underlying medical causes, coordinating care with the child's established medical home, and determining the necessity of referral to a higher level of psychiatric care.25 To properly care for children with complex needs, such as those with intellectual disabilities, autism spectrum disorders, or acute MBH crises, ED personnel require dedicated, suitable physical space and additional personnel resources.25

Furthermore, triage protocols must accommodate diverse populations. Children from various cultural, language, and social backgrounds—including those with differing gender identities and sexual orientations—may present unique challenges that require specialized skill sets and knowledge among emergency physicians, physician assistants, and nurses.25 Therefore, emergency care providers must commit to providing developmentally appropriate, culturally responsive, and trauma-informed care during the assessment and management of acute pediatric presentations.25

Standardization, Training, and Technology

The overall performance of a triage system is profoundly affected by the fidelity of its implementation and the consistency of the staff utilizing it. The structured complexity of leading five-level systems requires comprehensive support to ensure high inter-rater reliability.

The design of complex scales like CTAS is explicitly engineered to be conducive to computerization, allowing for decision support at the point of care.4 Such technological integration is vital for mitigating human error and maintaining high accuracy, especially when dealing with the vast array of presenting complaints and associated modifiers.4 As noted previously, the use of computerized decision support or paper-based reference tools, versus reliance on memory alone, is a critical variable that must be accounted for when analyzing and comparing triage accuracy data across different facilities.4

Moreover, effective implementation requires standardized, rigorous training. Prior to the adoption of a system such as RETTS-p, nurses completed extensive theoretical and practical training to ensure proficiency in applying the clinical signs, symptoms, and vital parameter measurements to assign appropriate priority levels.20 This commitment to continuous professional development is necessary to maintain system reliability and prevent degradation of performance over time.

Table 2: Key Challenges and Mitigation Strategies in PETS Implementation

Future Directions: Predictive Triage and Machine Learning

The evolution of PETS is moving towards enhanced decision support mechanisms, notably leveraging Machine Learning (ML) techniques. Recent research has explored novel methods for enhancing ML-based triage and ED management, specifically through sophisticated feature engineering methodologies aimed at forecasting patient arrivals and predicting outcomes. This technological advancement offers the potential to substantially improve existing systems like CTAS by optimizing model performance, enabling real-time decision-making, and facilitating optimized resource allocation based on predicted demand and acuity. Future studies are anticipated to focus on integrating these machine learning developments into mainstream triage protocols to further refine accuracy and efficiency.

Policy Recommendations and Conclusions

The evidence confirms that Pediatric Emergency Triage Systems require specialized algorithms that account for unique pediatric physiology and risk profiles, moving decisively beyond the "small adult" paradigm. The adoption of internationally recognized, five-level acuity scales is a prerequisite for standardizing care and improving outcomes globally.

A. The Requirement for Hybrid Safety Systems

It is concluded that no single static triage tool is fully comprehensive for pediatric emergency care. Triage must be viewed as a sequential process, not a singular assessment. Policy should mandate the integration of five-level triage scales (such as ESI or CTAS, which focus on initial stratification and resource needs) with validated, dynamic alert systems (such as PEWS or POPS). While static scales perform the vital function of instantaneous prioritization and resource matching upon arrival, dynamic alert systems provide the crucial safety mechanism for detecting physiological deterioration during extended wait times or in holding areas.

B. Prioritizing Infant-Specific Physiological Criteria

To mitigate the documented and clinically severe risk of undertriage in infants, PETS protocols must be refined to prioritize objective physiological data. Triage guidelines for all five-level systems should incorporate explicit, highly sensitive, age-stratified vital parameter criteria for infants and non-verbal children, ensuring that subtle signs of physiological distress are immediately elevated to high-acuity levels, overriding potentially misleading subjective symptoms or communication limitations. Systematic assessment of vital signs must be mandated for all children, irrespective of the initial presenting complaint.

C. Strategic System Selection Based on Context

The choice of a national or regional PETS must align with institutional resources and primary policy objectives.

High-Resource Settings: Systems like P-ESI, with its superior predictive validity for admission (AUC 0.78), are highly effective when the primary goal is operational efficiency, ED throughput management, and precise resource allocation.

Clinically Focused Systems: Systems like CTAS and the hybrid RETTS-p, which emphasize objective physiological signs and symptom severity, offer high reliability and strong correlation with clinical urgency, making them robust choices for settings prioritizing clinical purity over resource-driven categorization.

Resource-Constrained Settings (LMICs): In environments characterized by resource scarcity and high patient volume, simplified, clinically focused algorithms such as WHO ETAT must be prioritized. These systems ensure that the fundamental public health goal—rapid prevention of mortality through immediate, life-saving interventions—is met, rather than attempting to implement complex, resource-dependent models that fail during cross-cultural adaptation.

Investment in Implementation Fidelity

Finally, given the established complexity of five-level triage, sustained high performance hinges on investment in implementation technology and training. Policy mandates should require the adoption of computerized decision support systems to minimize inter-rater variability and maintain the high reliability demonstrated by leading systems. Furthermore, mandatory, continuous, and standardized theoretical and practical training for all emergency nursing staff must be implemented to ensure that the precision of the system design is reflected in its execution.