Technological Drivers of Military Triage Evolution from WWII to the Digital Battlefield

Early documented applications trace back to the 18th century, notably through the work of French military surgeon Baron Dominique Jean Larrey, who developed a rapid system for evaluating and categorizing wounded soldiers during combat.

The foundational principles of military triage, rooted in the French concept of trier (to sort or categorize) , were formally established in the military context centuries ago. Early documented applications trace back to the 18th century, notably through the work of French military surgeon Baron Dominique Jean Larrey, who developed a rapid system for evaluating and categorizing wounded soldiers during combat. This system laid the groundwork for modern triage, which fundamentally divides victims into three groups: those likely to live regardless of care, those unlikely to live regardless of care, and those for whom immediate care may positively influence the outcome.

By the time of World War II, the U.S. Army Medical Department had formalized a detailed "chain of evacuation". Wounded personnel progressed through several echelons of care, starting with aid posts and dressing stations, receiving stabilizing emergency care, and moving to field hospitals before reaching an Evacuation Hospital. Historically, the Evacuation Hospital was intended to be a large, stable facility, often supporting multiple divisions. Due to wartime necessity, however, its mission evolved to perform critical, life-saving surgery, mirroring the function of the British Casualty Clearing Station. This structured, yet often slow, movement utilized hospital trains, hospital ships, and truck transport. Early fixed-wing air evacuation was employed, managed by medical air evacuation transport squadrons, demonstrating its speed advantage for the critically wounded. Coordination among the Army Service Forces, the Chief of Transportation, and the Army Air Forces Command was paramount to managing the volume of traffic and the changing evacuation policy.

This baseline system, despite the dedication of personnel like flight nurses—who achieved a remarkably low en route fatality rate of only 46 deaths among 1,176,048 air-evacuated patients during the war —faced severe logistical limitations. Overall, the mortality rate for American soldiers who received medical care in the field or underwent evacuation stood at approximately 4 to 4.5 percent. This figure represents the maximum achievable survival rate given the technology and evacuation speeds available at the time.

Logistical Constraints Define Triage Efficacy

The medical achievements of WWII confirmed the effectiveness of professional, staged care, yet the final survival rate was fundamentally constrained by the velocity of transport. The fixed-wing aircraft used for air evacuation, while an improvement over ground transport, required established airfields and complex coordination. The logistical chain required wounded personnel to be stabilized and moved back toward established capacity, often involving long delays due to rough terrain or distance from suitable transport hubs.

The core limitation of the WWII system was that the medical units, such as the Mobile Surgical Units (MSUs) that operated close behind the lines , could only stabilize patients until ground or fixed-wing evacuation could transport them to the Evacuation Hospital. The system was structured as a staged evacuation (or triage d’attente), meaning critical surgical intervention was delayed until the patient could be safely delivered to a rear-area facility. This delay, often exceeding the critical physiological tolerance window for massive hemorrhage, prevented a greater reduction in mortality rates. The 4.5 percent post-injury fatality rate therefore serves as the critical baseline that reflects the practical limits imposed by 20th-century ground and fixed-wing transport velocity in forward combat zones.

The Rotary-Wing Revolution: MASH and the Cultivation of Speed (Korea and Vietnam)

The Helicopter Catalyst and the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH)

The invention and militarization of the rotary-wing aircraft provided the technological breakthrough necessary to shatter the logistical barrier that defined WWII casualty care. While a daring Army air rescue in Burma during WWII marked the first instance of medical evacuation by helicopter, it was the Korean War that saw the full operational integration of air evacuation.

The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH), which saw its first active deployment during the Korean War, was the corresponding doctrinal innovation. MASH units were purposefully placed close to the front lines, equipped to provide effective surgical intervention. The revolutionary synergy lay in pairing the MASH concept with the newly operational helicopter MEDEVAC system. The U.S. Army 2nd Helicopter Detachment, flying the Bell H-13, became operational as an attachment to the 8055th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in late 1950. These helicopters functioned as "air ambulances," swiftly transporting the wounded, often within minutes of injury, directly from the point of impact to the MASH unit. During the Korean War, roughly 17,000 soldiers were evacuated by air.

This combination of proximity and speed yielded an immediate, quantifiable improvement in survival rates. The use of aerial MEDEVAC, coupled with early treatment in MASH units, resulted in a dramatic reduction in the post-evacuation fatality rate for the Army, dropping from the WWII baseline of 4.5 percent to 2.5 percent during the Korean War.

Vietnam and the Institutionalization of the "Golden Hour"

The Vietnam War further refined and institutionalized the air evacuation system. The Bell UH-1 helicopter, universally recognized as the "Huey" and known by the call sign "Dustoff," became the dedicated icon of military medical evacuation. These helicopter ambulances moved over 900,000 wounded troops during the conflict. The capacity and velocity of the Huey enabled medical personnel to begin triage and stabilization the moment the aircraft "dusted off" the scene, often long before the patient reached the field hospital.

This systematic reduction in transport time formalized the concept of the "Golden Hour," often cited as the critical first 60 minutes after a traumatic injury, during which definitive surgical care offers the greatest chance of survival. MASH units prioritized cutting down patient mortality during this crucial period. The combined efficiency of rapid transport and immediate surgical access resulted in an unprecedented casualty outcome: the mortality rate for wounded soldiers plummeted to approximately 1 death per 100 casualties (1 percent).

Beyond logistics, medical practices advanced significantly during this era. This included the prompt administration of fresh whole blood at forward aid stations and the adoption of modern anesthetics. Specifically, Ketamine, an ideal anesthetic for hypovolemic trauma patients, was introduced in the 1960s and quickly utilized in military treatment facilities, often procured through unconventional means when military channels lagged.

The impact of the helicopter was not limited to transport; it fundamentally transformed the medical process itself. By allowing medical personnel to begin stabilization and sorting en route, the critical process of triage was collapsed into the evacuation time itself. The rotary-wing aircraft became, in effect, a mobile trauma bay, enabling the MASH surgeon to receive a pre-stabilized, pre-sorted patient. This optimization of pre-hospital and en route care maximized operating room throughput and utilization of the "Golden Hour."

The MASH Paradox—Proximity vs. Vulnerability

Although the MASH unit was a revolutionary organizational structure, its success introduced a logistical tension. MASH units were intended to provide effective surgical intervention close to the fighting while allowing the surgeon to maintain protection. A standard MASH unit typically possessed 60 beds and was equipped to support up to 20,000 soldiers. However, the expansion in workload often exceeded the unit's capacity, making rapid evacuation of stabilized patients essential to maintaining operational integrity.

The MASH required significant personnel, equipment, and logistical sustainment, making it a relatively large, static presence compared to the pace of modern maneuver warfare. The vulnerability inherent in maintaining a large, fixed hospital structure close to a non-linear front line prompted military planners to seek smaller, more agile solutions in subsequent conflicts. While the MASH proved the doctrinal necessity of forward surgery to save lives, its scale highlighted the logistical unsustainability of large, centralized forward hospitals in dynamic environments. This tension catalyzed the shift toward modular, smaller surgical teams.

Doctrinal Evolution: Modularization and Damage Control (Post-Vietnam to OIF/OEF)

The Shift from MASH to Modular Forward Surgery

The operational context of modern non-linear warfare necessitated a dramatic restructuring of forward medical capabilities. The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital era formally ended when the last unit was deactivated in 2006. MASH units were ultimately replaced by larger, theater-level facilities known as Combat Support Hospitals (CSH) (Role 3), and by small, highly mobile elements at the front: the Forward Surgical Team (FST).

The FST concept, introduced in the early 1990s and fielded in 1997, represented a major doctrinal shift. FSTs consisted of 20 personnel and equipment, capable of being parachuted in. An FST was designed to perform 30 life-saving operations in 72 hours. Their mission was strictly to provide life-saving and/or sustaining surgical care, not definitive treatment, before the service member was evacuated further down the line of care.

The doctrine evolved further in 2013 with the introduction of the Forward Resuscitative Surgical Team (FRST). This modification focused specifically on enhancing patient resuscitation capabilities. The structural change was telling: the FRST maintained 20 personnel but exchanged one general surgeon and two operating room (OR) nurses for the addition of a second orthopaedic surgeon and two emergency room (ER) physicians. This compositional change strategically augmented the team’s ability to stabilize life-threatening injuries and physiological derangements, reflecting the increasing complexity of blast and fragmentation injuries seen in recent conflicts.

Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR) as the Modern Triage Philosophy

The modularization of surgical capacity aligns with the modern trauma doctrine of Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR). DCR dictates a shift away from immediate definitive surgical repair in the field, favoring instead temporizing measures that prioritize controlling hemorrhage, relieving airway obstruction, and addressing physiological derangements, followed by staged, definitive care in a higher echelon.

The modern triage process begins at Phase Zero, Damage Control Ground Zero, which implements early prehospital measures. Given that uncontrolled hemorrhage accounts for over 90 percent of combat fatalities , DCR mandates immediate hemorrhage control using mechanical adjunct devices such as tourniquets and junctional devices, coupled with a fluid resuscitation strategy that prioritizes the use of whole blood and tranexamic acid (TXA).

In practice, the FST/FRST triage paradigm is strictly time-sensitive. The team's primary role is to buy time for the patient. Musculoskeletal injuries without an immediate life- or limb-threatening component are managed at the bedside with immobilization, débridement, and antibiotics, awaiting transfer. The team’s operational challenge is determining resource allocation for the single operating room available—a triage decision focused solely on who requires immediate damage control intervention to survive evacuation.

This represents a profound doctrinal shift. The MASH aimed to provide comprehensive surgery and holding capacity. In contrast, the FRST explicitly limits its capacity and holding time (to 72 hours maximum). The personnel change—fewer general surgeons and more emergency physicians—demonstrates a formal commitment to prioritizing pure resuscitation capabilities (DCR) over comprehensive surgical volume. Triage at the forward echelon (Role 2) is now entirely focused on physiological stabilization for rapid evacuation to the CSH (Role 3).

Outcomes and the Challenge of En Route Care

The effectiveness of modular, speed-centric care in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan is evident in the sustained reduction of overall casualty rates. Since WWII, the combat fatality rate has fallen from 55 percent to 12 percent, and the Killed in Action (KIA) rate has dropped from 52 percent to 5 percent.

However, the analysis of recent conflicts introduces a critical nuance: the Died of Wounds (DOW) rate was found to be higher in Iraq and Afghanistan than in Vietnam. This counterintuitive finding highlights the severity of modern blast and fragmentation mechanisms of injury, particularly from IEDs and mines. High-velocity fragments cause extensive tissue destruction, secondary missile effects, and massive contamination, complicating resuscitation efforts. This means that while the modern trauma system is exceptionally effective at retrieving and stabilizing casualties (resulting in a lower KIA rate), the sheer lethality and complexity of the resulting wounds challenge even the most aggressive DCR protocols, causing a higher proportion of severely wounded individuals to succumb to their injuries despite reaching advanced medical care.

The structural necessity of rapid evacuation from the FRST to a CSH imposes significant demands on the transport phase. As forward surgical teams reduce their footprint, the responsibility for maintaining critical stabilization shifts entirely to the MEDEVAC platform itself. Helicopters (such as the UH-60 Black Hawk) must function as mobile critical care units. This necessitated the development of sophisticated En Route Care (ECC) capabilities, including specialized Patient Transfer Units (PTUs) equipped with portable ventilators, multi-parameter monitors, and oxygen systems, designed to ensure safe air evacuation and integrated physiological monitoring. The ability to monitor patient status and physiological data trends under harsh transport conditions is crucial, confirming that the air platform is no longer simply transport, but an indispensable link in the continuum of care.

The Digital Continuum: Telemedicine and the Future of Remote Triage

Historical Precursors and the Emergence of Telemedicine

While the formal definition of military telemedicine is a modern phenomenon, the transmission of medical data over distances has historical precedent, such as the use of the telegraph for medical supply orders and casualty lists during the Civil War. The ability to transmit pre-hospital data gained momentum in 1967 with the pioneering use of voice radio channels to transmit electrocardiographic rhythms from fire-rescue units to hospitals in Miami.

Formal institutional investment in military telemedicine began in the early 1990s. The Medical Advanced Technology Management Office (MATMO) was established in 1993, driven by the need to develop, procure, and deploy filmless medical diagnostic imaging systems (MDIS). MATMO was later reorganized into the Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center (TATRC) in 1998. TATRC championed the use of advanced technologies, including secure global positioning systems, wireless networking, and remote monitoring, with the consistent goal of supporting deployed forces. Telemedicine now facilitates the entire continuum of care, from Echelon 1 (point of injury) all the way back to Continental United States (CONUS) hospitals.

Telemedicine and Predictive Triage Decisions

The most significant technological advancement impacting future triage decisions is the development of remote diagnostics and predictive analytics. Combat developers are focusing on "wear-and-forget" Physiological Status Monitors (PSMs) that continuously measure physiological signals like the electrocardiogram and respiration.

Since the median survival time from severe hemorrhage is only two to three hours , the window for identification and intervention is critically narrow. Researchers are now developing machine learning algorithms that use low-level physiological signals from wearable devices to accurately model the status of circulating blood volume. These algorithms show promise in discriminating between the physiological signals associated with normal physical activity and those indicating central hypovolemia (hemorrhage).

The objective, data-driven assessment of hemorrhage risk allows medics to initiate life-saving DCR measures (such as whole blood transfusion) far forward, often before clinical signs of shock become manually evident. This capacity shifts triage from a manual, reactive assessment to a data-driven, predictive assignment of resources. A system that reliably predicts hypovolemia before a patient presents with obvious clinical symptoms fundamentally shortens the critical reaction time, directly impacting the prehospital triage decision regarding the destination and priority of intervention.

Emerging Logistical and Operational Technologies

The rise of Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS), or drones, presents both opportunities and challenges for military medical operations. UAS have proven effective in delivering medical supplies, including critical blood products, medications, and portable equipment, addressing significant logistical constraints in austere environments.

However, the widespread adoption of digital and remote medical platforms introduces profound strategic dependencies. The ability to save lives relies on data moving effectively across all echelons. Technology needs for en route care demand interoperability of medical information, equipment, and supplies across the global military health system. Future trauma systems must ensure that sensors, decision support tools, and algorithms are integrated into secure tactical networks. The failure of network infrastructure, challenges in achieving data standards, or targeted interference from electronic warfare and counter-UAS measures could cripple the entire digital continuum of care. This elevates cybersecurity and data interoperability to the level of critical medical capability, representing a new non-medical strategic vulnerability in the trauma system.

Synthesis and Strategic Implications

V.A. Correlating Technological Velocity and Casualty Survival

The historical record demonstrates a strong causal link between technological advances in transport and facility design and improvements in casualty survival. The dominant factor has been the exponential increase in the velocity and intimacy of care—the speed at which the patient can reach effective surgical intervention or, conversely, the speed at which surgical capability can reach the patient. Each measured reduction in post-injury mortality coincides directly with a technological leap that dramatically reduced the injury-to-surgery interval.

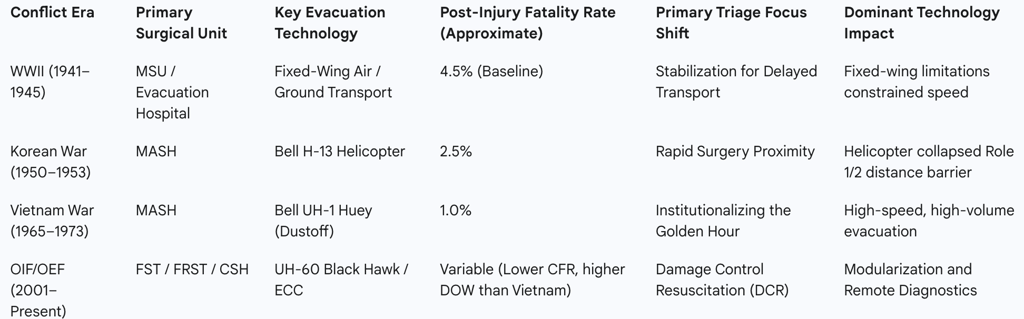

The following table summarizes this correlation across conflict eras, illustrating how technological and doctrinal shifts drove measurable improvements in outcome:

Comparison of US Military Casualty Care Outcomes by Conflict Era

Structural and Personnel Shifts: The Modularization Imperative

The transition from the MASH to the modern modular system (FST/FRST) was a direct response to the lessons learned about battlefield agility and the optimal timing of surgical intervention. The MASH, while transformative, prioritized comprehensive care and holding capacity (60 beds). The FST and FRST models prioritize agility and hemorrhage control. The intentional reduction of general surgeons and the addition of ER physicians and orthopaedic surgeons in the FRST reflect a strategy to maximize DCR capability and stabilize the complex musculoskeletal and blast injuries prevalent in modern combat.

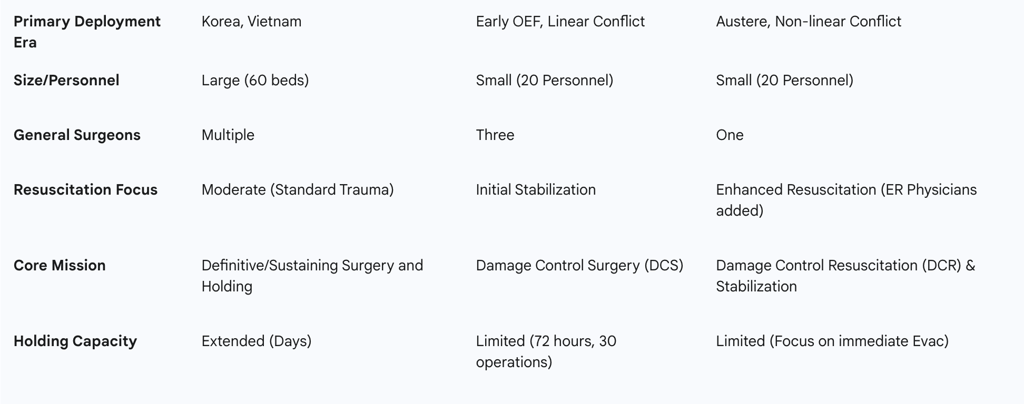

The table below contrasts the strategic decision points in forward surgical doctrine:

Forward Surgical Capabilities: MASH vs. Modern Modular Teams

This comparison underscores the philosophical pivot in military medical doctrine: the goal of the modern forward unit is not to repair, but to rapidly stabilize the patient for evacuation. The limitations in imaging (reliance on ultrasonography) and the reduced surgical staff demonstrate the trade-off accepted to achieve maximum mobility and DCR capability in an austere environment.

Conclusions and Strategic Imperatives

The evolution of military triage is defined by the relentless pursuit of speed, enabled first by rotary-wing transport and now by advanced digital connectivity. The data conclusively shows that the velocity of care—both physical and informational—is the preeminent determinant of survival.

Prioritization of Remote Hemorrhage Detection: Given the severity of modern wounds and the fact that hemorrhage remains the leading cause of preventable combat death , the most critical investment is in technologies that enable predictive triage. Research and deployment efforts must focus on Physiological Status Monitors (PSMs) and machine learning algorithms that provide real-time, objective metrics of circulating blood volume status. This capability will maximize the effectiveness of Phase Zero DCR interventions and further compress the injury-to-treatment time, which is essential for reducing the persistent Died of Wounds rate.

Strategic Focus on Digital Interoperability and Resilience: The future trauma system depends on the seamless movement of patient data from the point of injury (Echelon 1) through the modular echelons (FST/FRST) and into definitive care. The technological dependency on advanced patient monitoring systems and telemedicine consultations means that system integrity is a life-or-death operational requirement. Therefore, focused research must define common data standards and implement cyber-secure, resilient networks (following the DevSecOps cycle) to ensure that the medical system cannot be disabled by electronic warfare or network failure.

Integrating Autonomous Logistics with Manned Evacuation: While Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) demonstrate great promise for logistical resupply (e.g., blood products) in high-risk zones , current limitations in payload capacity and vulnerability to adversarial countermeasures suggest that manned rotary-wing platforms will remain the gold standard for casualty evacuation (CASEVAC) due to superior reliability and capability in complex environments. Future strategy requires an integrated air platform architecture that intelligently uses UAS for resupply while securing reliable, rapid manned MEDEVAC routes for critical patients.

Addressing Ethical Complexity in Resource Allocation: As technology enables remote triage decisions under conditions of duress and scarce resources, it is necessary to establish clear ethical guidelines and provide robust psychological support. Health care professionals tasked with making difficult choices based on remote data must have mechanisms in place, such as structured debriefing, to help them navigate and justify critical ethical decisions made under combat pressure.