Specialized Mental Health Triage Scales in Psychiatric Emergencies

Triage in the mental health context is the essential clinical function that determines a patient's immediate need for assessment and service provision. The mental health triage service typically serves as the most common entry point into the mental health system, often operating 24 hours a day, seven days a week, across public mental health services.

Triage in the mental health context is the essential clinical function that determines a patient's immediate need for assessment and service provision. The mental health triage service typically serves as the most common entry point into the mental health system, often operating 24 hours a day, seven days a week, across public mental health services. The primary goal of triage, derived from the French word "trier" (to sort) , is to provide an initial assessment to classify patients based on the severity of their illness or risk, thereby optimizing resource usage and timing of care. The process identifies the type and urgency of response required from specialist mental health or other services.

A critical operational factor in mental health triage is the modality of assessment. Unlike general emergency department (ED) triage, which often relies on immediate face-to-face assessment of physiological findings, mental health triage is frequently conducted remotely, such as over the telephone. This operational necessity dictates that standardized guidelines and triage scales must be robust enough to classify urgency without assuming direct visual or physical assessment. This constraint is significant because it fundamentally shifts the basis of assessment away from objective physiological data (e.g., Glasgow Coma Scale, hemodynamic status ) and toward behavioral indicators and reported subjective data. Consequently, scales must be structured to rely heavily on self-reported risk (e.g., suicidal ideation with plan, means, and intent) and observable behavioral cues relayed verbally, factors that are inherently more susceptible to clinical variability and observer bias compared to standardized vital signs. Therefore, specialized instruments must compensate by assigning higher weight to stated risks to maintain safety standards in the absence of complete physiological confirmation.

Distinguishing Psychiatric Acuity from Somatic Urgency

Effective triage requires a clear understanding of the differential criteria used to determine acuity in medical versus psychiatric emergencies. General medical triage systems prioritize immediate threats to life based on physiological instability, such as trauma or cardiac events. In contrast, mental health triage assesses and prioritizes based on the patient's current clinical condition, specifically focusing on the presence of priority indicators and "danger signs" that require immediate service intervention. Mental health clinicians conducting triage explicitly look for the risk of harming themselves or others, while physical triage focuses on the threat to the patient’s life. This dual focus means that psychological triage incorporates the patient's condition and behavior, such as aggression, rather than just physical metrics.

A major clinical pitfall identified in the emergency setting is the failure to appreciate that a mental health presentation can pose a risk that is equally acute or dangerous as a medical or surgical presentation. This oversight can lead to systemic risk. When both physical and behavioral issues are present, the governing standard mandates that the patient must be placed in the highest appropriate category derived from either assessment. However, historical practices indicate that clinicians, particularly those lacking specialized mental health training, may allow negative personal feelings or discomfort regarding a psychiatric patient to inappropriately influence the assigned acuity score. To mitigate this ethical and clinical risk, protocols must explicitly require that the presence of immediate danger to self or others—a core psychiatric criterion—must automatically override stable physiological markers when assigning high-acuity levels (Level 1 or 2). This ensures that critical safety needs are prioritized above staff comfort or perception of somatic stability.

Review of Global Triage Systems and Integration Deficits

International triage systems, such as the Australasian Triage Scale (ATS) and the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS), are widely implemented five-level systems that categorize patients based on the urgency of intervention required. These scales define time-to-treatment benchmarks ranging from Category 1 (immediate treatment, requiring resuscitation) to Category 5 (non-urgent, requiring treatment within 120 minutes).

A significant limitation of general scales like the ATS has been repeatedly demonstrated in the literature concerning mental health presentations. Research indicates that the specific mental health descriptors embedded within the general ATS framework are not as reliable as those found in specialized mental health triage scales. This deficiency directly compromises the validity of the initial triage assessment in the ED and consequently hinders the ability of mental health clinicians to respond in a timely and appropriate manner.

The systemic consequence of this inadequacy is severe misclassification. Studies examining triage tools without adequate, specialized mental health descriptors found that approximately 70% of mental health presentations were mis-categorized, with 97% of those instances resulting in assignment to a lower urgency category than clinically warranted. This demonstrates a critical systemic bias where physiological stability is erroneously interpreted as overall low urgency, neglecting acute psychiatric risk. This under-triage leads to prolonged wait times, increased adverse outcomes , and potential escalation of agitation and violence, which ultimately necessitates more intensive (and costly) resource management, establishing a robust clinical and financial imperative for adopting specialized tools.

The CTAS, which shares structural similarities with the ATS, attempts to overcome these limitations through the incorporation of second-order modifiers. These modifiers are designed to assign acuity based on non-physiological factors, specifically addressing concerns related to patient welfare, conflict, unstable situations, risk of flight, suspected assault, and family distress. Targeted education and training focusing on the rigorous use of these second-order modifiers have been identified as a direct operational strategy to improve the reliability and validity of CTAS when assigning urgency ratings to mental health presentations. This structured approach forces clinicians to systematically consider the complex, non-physical dimensions of psychiatric acuity that are ignored by traditional physiological assessments.

Architecture of Specialized Mental Health Triage Scales

Dedicated Five-Level Acuity Systems (ATS Mental Health Module)

In jurisdictions where general emergency systems are mandated, specialized mental health triage tools are often implemented as specific modules or guidelines integrated into the primary five-level scale (e.g., the Victorian Emergency Department Mental Health Triage Tool or ATS-derived guidelines). These specialized systems maintain the structure of five acuity levels but redefine the clinical discriminators based on dynamic behavioral risk assessment.

Category 1 (Immediate) demands rapid, high-intensity management focused entirely on physical safety and containment. This level is defined by definite danger to life (self or others) or a severe behavioral disorder with an immediate threat of dangerous violence.15 Observed presentations include violent behavior, possession of a weapon, or major self-harm within the ED setting.15 The mandated general management principle for Category 1 requires continuous visual surveillance at a 1:1 ratio, immediate alert to ED medical staff and mental health triage, and ensuring adequate personnel for restraint or detention based on local legislation.15

Category 2 (Emergency) is assigned when there is probable risk of danger to self or others.15 Crucially, this category includes patients who are physically restrained in the emergency department.15 The classification of a physically restrained patient as Category 2, even if the primary risk is only deemed probable, underscores the immense resource consumption and immediate high-risk management need associated with this status. These categories demonstrate that specialized scales shift the definition of "emergency" away from purely physiological collapse and toward imminent behavioral threat.

Specialized Predictive Instruments (e.g., Crisis Triage Rating Scale - CTRS)

Beyond the standard five-level acuity systems designed primarily to manage time-to-treatment in the ED, specialized instruments exist to rapidly determine disposition. The Crisis Triage Rating Scale (CTRS) is a well-established, brief, clinician-rated instrument designed to rapidly screen psychiatric patients in crisis and help differentiate those who require hospitalization from those who are suitable for outpatient crisis intervention.18

The CTRS utilizes a three-factor model, with each factor rated on a 1-5 scale (where 1 indicates the highest risk/lowest function):

Dangerousness: Evaluates current suicidal or homicidal ideation, recent dangerous attempts, and unpredictable, impulsive, and/or violent behavior.

Support System: Assesses the availability of immediate external support, such as family, friends, or agencies, to provide necessary buffers.

Ability to Cooperate: Measures the patient's willingness and capacity to cooperate with the assessment and subsequent treatment planning.

Studies utilizing the CTRS have established clear predictive validity concerning resource utilization. The established clinical threshold for determining disposition is a score of 9 or below, which strongly correlates with the need for hospitalization. Conversely, scores of 10 and above typically indicate that hospitalization is not immediately necessary and that the patient is suitable for intensive outpatient crisis intervention.18

This function represents a paradigm shift from standard acuity triage. Unlike general scales, which measure time-to-treatment, the CTRS functions as a predictive model for institutional disposition. By quantifying the likelihood of inpatient admission, this tool transitions the triage process from a simple waiting-list manager into a key instrument for resource allocation. Policy makers seeking to reduce inappropriate ED boarding and optimize bed flow should mandate the use of CTRS-like models early in the crisis assessment pathway to rapidly divert low-risk patients who maintain community protective factors.

The inclusion of the "Support System" (Factor B) as a primary high-risk factor is particularly instructive. A low score in this area (e.g., "No family, friends, or others" or "Agencies cannot provide immediate support needed" 18) acknowledges that social determinant factors and systemic failures are critical drivers of crisis severity. A patient lacking community buffers will inherently rely more heavily on institutional safety structures, thereby requiring a higher level of care, regardless of the severity of immediate clinical pathology. Therefore, specialized crisis protocols must extend triage beyond immediate symptomatology to include a comprehensive assessment and quantification of social risk factors.

Rigorous Clinical Assessment and High-Risk Identification

Risk Assessment in Triage

High-acuity psychiatric triage mandates a swift, structured approach to identifying active and acute risks. Triage nurses can accurately identify the urgency of mental health presentations using defined clinical criteria.10 Patients with acute psychotic symptoms, for instance, are significantly more likely to be triaged as high urgency (Code 2).10 The most critical factor in risk stratification is the assessment of lethality, with the highest urgency ratings assigned when acute suicidal or homicidal ideations are present alongside a defined plan, means, and intent.17 Other indicators necessitating immediate, high-level attention (Category 1) include observable behaviors such as extreme agitation, restlessness, bizarre/disoriented behavior, or reported command hallucinations to harm self or others that the person cannot resist.15

Triage of Acute Behavioral Disorders: Violence, Agitation, and Behavioral Disturbance

Severe behavioral disturbance or immediate threats of dangerous violence are primary discriminators for the highest triage category. Observed violent behavior, the possession of a weapon, or major self-harm within the ED mandate a Category 1 Immediate classification.15

General management principles in these situations prioritize containment and safety, requiring continuous visual surveillance, immediate alerting of clinical and security personnel, and preparation for restraint/detention in line with local legal statutes.15 Clinicians must also consider the effects of substances, as intoxication by drugs or alcohol is known to cause an escalation in behavior that necessitates management adjustments.15

Medical-Psychiatric Interface and Mandatory Clearance

A fundamental and non-negotiable step in the triage and evaluation of psychiatric patients is the Medical Clearance process. This requires the performance of a psychiatrically relevant and focused medical assessment to investigate and rule out any organic etiology or concurrent medical condition contributing to the presenting psychiatric complaint.21

Medical clearance should indicate, with reasonable medical certainty, three core findings: first, there is no known contributory medical cause for the patient’s presenting complaints requiring acute medical intervention; second, there is no active medical emergency; and third, the patient is medically stable enough for transfer to the intended dispositional setting (e.g., a psychiatric hospital or outpatient setting).21

In terms of efficiency, robust clinical evidence indicates that the majority of significant medical problems and substance abuse issues in ED psychiatric patients can be identified by obtaining initial vital signs and conducting a basic history and physical examination.23 Consequently, the policy of performing universal laboratory and toxicological screening on all patients presenting with psychiatric complaints has been demonstrated to be of low yield and should not be mandated as standard practice.23

The necessity of medical clearance reinforces a critical policy dictum: when both physical and behavioral problems are present, the patient must be triaged and placed in the highest appropriate category based on either domain.2 Failure to diligently screen for organic causes—such as hypoxia, metabolic derangement, or acute delirium masquerading as functional psychosis—is a significant triage pitfall 6 that risks patient mortality due to delayed treatment of underlying physical emergencies. Triage protocols must explicitly structure medical reassessment using physiological discriminators to override the mental health presentation whenever objective medical instability is detected.

Identifying and Prioritizing High-Acuity Overlap Syndromes (Delirium and Catatonia)

The clinical interface between medicine and psychiatry is most critically demonstrated in the high-acuity syndromes of delirium and catatonia, which often present with bizarre or altered behavior. Failure to distinguish these from functional psychiatric illness can be fatal. Delirium is defined as an acute medical problem that causes new onset bizarre behavior.6 Catatonia, characterized by symptoms such as immobility, stupor, mutism, staring, and autonomic abnormalities 24, presents a severe diagnostic challenge.

Crucially, catatonia frequently overlaps with and coincides with delirium.25 In clinical cohorts, a significant proportion of patients (49%) meeting criteria for catatonia simultaneously met criteria for delirium.24 Furthermore, the severity of catatonia correlates with the likelihood of delirium; patient assessments presenting with three or more DSM-5 catatonia symptoms had, on average, 27.8 times the odds of having delirium compared with those with zero criteria present.24

The policy imperative here is the recognition that an unresponsive or rigid patient, potentially exhibiting catatonic stupor or mutism, may be mistakenly assigned a lower urgency rating (Category 4 or 5) due to their lack of overt, aggressive activity. This assessment error is extremely dangerous, as the high mortality risk associated with untreated malignant catatonia or underlying organic causes (delirium) demands an immediate, high medical acuity response equivalent to Level 1 or 2.25 Triage protocols must incorporate standardized, rapid screening instruments (such as the Bush Francis Catatonia Screening Instrument) to detect catatonia signs, treating them as medical red flags that mandate immediate medical stabilization and intervention, bypassing typical non-urgent psychiatric assessment pathways.

Psychometric Validation and Quality Assurance in Triage

Analysis of Inter-Rater Reliability (IRR) in Mental Health Triage

Inter-Rater Reliability (IRR), the consistency of scores assigned by different clinicians using the same scale, is the cornerstone of standardized, equitable, and safe triage practice.14 Historically, clinical judgment in psychiatric settings, even among experienced practitioners, has shown low reliability. Previous studies have reported low interrater agreement for severity of depression ratings (Kappa $\approx$ 0.52) and psychiatric medication decisions (Kappa $\approx$ 0.6).27 When general ED triage scales (like the CTAS) were applied to mental health scenarios without specialized structure, the overall Fleiss' kappa measured only 0.312, representing only fair agreement.14 This inconsistency introduces significant risk, leading to variable patient categorization and treatment delays across different providers and shifts.

Impact of Explicit Criteria and Structured Scoring on Reliability

The evidence overwhelmingly supports the use of structured assessment instruments and explicit, quantified criteria as the most effective mechanism for achieving improvements in IRR in psychiatric settings.27 Policies seeking to standardize acute mental health assessment must prioritize scales that use numerical aggregation of weighted factors over descriptive, categorical models.

A direct comparison of scoring methodologies demonstrated this disparity unequivocally. The Continuous Psychiatric Care Department’s (CRPT) triage tool, when assessed using its numerical score, exhibited excellent IRR (Cohen's Kappa = 0.894).28 Conversely, when the same tool was evaluated based on its categorical color/risk classification, the reliability was very poor (Cohen's Kappa = 0.277).28 This disparity is crucial for policy formulation: the adoption of factor-based, numerically aggregated scales, such as the CTRS total score or the CRPT score, significantly mitigates subjective clinical interpretation and clinician variability, providing a standardized foundation for safe and equitable care delivery.22 High reliability (near 0.9) also reduces internal staff friction, which often manifests as frequent disagreements about the urgency of care for psychiatric patients.28

Furthermore, accuracy is demonstrably improved by requiring clinicians to articulate their justification through structured modifications. Nurses who utilized the non-physiological second-order modifiers within the CTAS system recorded greater accuracy in their urgency ratings.14 The success of these structured approaches suggests that even emerging technologies, such as advanced language models (LLMs/GPT), show promise in supporting clinical workflows by replicating clinical reasoning with moderate to substantial IRR (Kappa $\approx$ 0.76–0.78) in determining risk and urgency.

Predictive Validity: Triage Scores as Determinants of Hospitalization and Adverse Outcomes

Predictive validity confirms the clinical utility of a triage scale by assessing its ability to predict relevant outcomes, such as the need for inpatient hospitalization, utilization of institutional resources, or subsequent adverse events. The specialized CTRS has proven valuable in this regard, demonstrating similar predictive validity to other specialized instruments when correlated with disposition and discharge variables.28 Specifically, the CTRS score reliably predicts the need for hospitalization.18

However, the overall validity of established triage systems remains moderate to good, with performance varying considerably.30 While triage scales are generally safe—the risk of death for patients categorized as least urgent is small 31—they cannot solely determine disposition, as some low-urgency patients may still require hospitalization.31

The predictive success of tools like the CTRS emphasizes the importance of non-clinical factors in disposition planning. Since the CTRS weighs Support System and Ability to Cooperate alongside Dangerousness, its predictive power validates the clinical understanding that psychosocial stability is a powerful protective factor. A patient with high clinical symptoms but a robust, functioning support network and willingness to cooperate (high CTRS score) is significantly less likely to require inpatient admission than a patient with moderate symptoms but zero support and active non-cooperation (low CTRS score). Policy must therefore mandate that triage scales be designed to quantify and prioritize these psychosocial determinants of health, leveraging them as effective predictors of resource utilization.20

Implementation Best Practices and System Optimization

Required Core Competencies for Emergency Mental Health Triage Clinicians

Effective, specialized mental health triage cannot be reliably performed by staff with only basic nursing education. It requires designated professionals, typically emergency or mental health nurses, who possess specialized competencies across knowledge, skills, and attitude domains.32 These clinicians function not only as assessors but also as crucial flow managers who mitigate systemic risk.

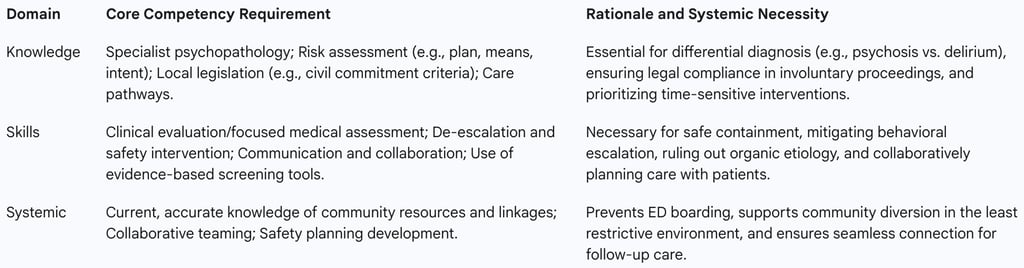

Table 3. Essential Competencies for Acute Mental Health Triage Clinicians

Specialist knowledge must include risk assessment, psychopathology, triage tools, and local legal regulations concerning mental health and substance use disorders. Required skills encompass clinical evaluation functions, effective communication, collaboration, and the exhibition of ability to effectively triage crisis situations based on urgency. Crucially, the attitude domain requires staff to operate with non-judgmental, confident, trauma-informed, and culturally responsive approaches, which are necessary to ensure person-centered care and maximize patient engagement in the crisis response.

Training and Education Strategies for Enhancing Triage Accuracy

The integrity of a specialized triage scale depends entirely on the fidelity of its implementation. Mental health services must ensure that staff are formally trained in the use of well-developed triage assessment protocols and tools. Training programs must introduce the basic concepts of the mental health triage tool, explain the application of those concepts, and provide clear guidance on intentional decision-making to direct the individual to the most appropriate level of care during a crisis.

Empirical studies confirm the tangible benefits of formalized training. The implementation of a mental health triage scale supported by a comprehensive educational package led to demonstrated system improvements, including a decrease in average wait times and an increase in customer satisfaction, with the tool being considered appropriate by clinical practitioners following training. Specific focus on the utilization of complex criteria, such as the CTAS second-order modifiers, during orientation and ongoing education is paramount to improving the reliability and accuracy of urgency ratings.

Workflow and Throughput Management

Accurate and timely mental health triage is inextricably linked to overall patient flow and mitigation of systemic bottlenecks within the Emergency Department. ED crowding is a major patient safety issue associated with increased patient mortality, delayed resuscitation efforts, and prolonged length of stay (LOS).

Specialized mental health triage tools act as powerful levers for flow control. Their use improves the safety of triage practices, assists in differentiating acuity, enhances communication between ED and mental health staff, and demonstrably contributes to reduced wait times and decreased volatility within the emergency setting. Studies have shown that dedicated mental health nurses utilizing these specialized tools in the ED achieved shorter wait times and more efficient referral pathways.

Crucially, inaccurate triage, particularly under-triage , is a primary driver of systemic inefficiency, leading to "access block," prolonged ED LOS, extended waiting times, and poor patient throughput. If a high-acuity patient is misclassified, their condition may escalate, leading to higher resource utilization (e.g., requiring physical restraint) and significant financial and medicolegal risk for the healthcare system. Policy must, therefore, recognize specialized triage personnel as essential capacity and flow managers. Furthermore, clinical guidelines strictly stipulate that patients requiring inpatient treatment must not be "boarded" in the emergency department, as this practice compounds crowding and compromises quality of care.

Legal and Ethical Framework for Acute Behavioral Interventions

Ethical Principles Guiding Triage Decisions

Triage in the psychiatric emergency setting is uniquely fraught with ethical dilemmas, particularly when assessing patients who lack capacity or pose an imminent danger. Clinicians must balance competing ethical principles in rapid succession, particularly Autonomy (respecting self-determination), Beneficence (acting in the patient’s best interest), and Non-maleficence (doing no harm).

The immediate demands of safety and risk containment—the core function of high-acuity triage—often require the clinician to override the patient’s autonomy to uphold the principles of beneficence and non-maleficence. For instance, involuntary assessment or detention is justified when there is a definite or probable risk of harm to self or others.

Legal and Clinical Standards for Restraint and Seclusion

The use of physical restraint is a high-risk clinical intervention that raises immediate ethical conflicts, necessitating careful balancing of human rights, ethical values, and clinical effects. In the triage process, physical restraint in the ED is an objective clinical marker that automatically assigns the patient to a high-urgency category (Category 2: Emergency).

While informed consent must always be obtained for health procedures, this requirement can be legally waived in an emergency situation. In such cases, the decision to use restraint or seclusion must be based strictly on the principle of providing the "greatest benefit to the person". Management protocols must focus on the regularization of physical restraints, rather than their elimination, by ensuring adherence to ethical guidelines.

In this context, the triage score derived from a structured, validated scale serves a critical medicolegal function. It provides the necessary objective documentation to justify the clinical decision to violate a patient’s autonomy through involuntary holds or restraint. A scale with demonstrated high reliability (e.g., Kappa ≈ 0.9) provides a strong, defensible clinical rationale, whereas reliance on low-reliability, subjective assessments significantly increases the institution’s medicolegal vulnerability. Therefore, specialized scales must incorporate explicit criteria (e.g., "Severe behavioural disorder with immediate threat of dangerous violence" ) that establish the legally mandated emergency threshold required to authorize restrictive interventions.

Finally, ethical considerations extend to disposition decisions, including high-risk discharges. Clinicians must ensure that high-risk patients being discharged are linked seamlessly to follow-up contacts, utilize collaborative decision-making, and develop effective safety plans in the least restrictive environment possible.

Future Directions and Policy Recommendations

Based on the synthesis of validation studies, system performance data, and ethical considerations, the following policy recommendations are presented to enhance the safety, reliability, and efficiency of mental health triage in psychiatric emergencies:

Mandate Enhanced Psychometric Performance

Policy should mandate the adoption of structured, quantitative, factor-based triage instruments (e.g., CTRS score, CRPT score) over purely descriptive or categorical scales for all acute psychiatric presentations. The documented superior Inter-Rater Reliability (IRR ≈ 0.9) of numerical scoring minimizes subjective variance, standardizes clinical judgment, and strengthens the clinical and medicolegal justification for high-acuity interventions (e.g., involuntary holds and restraint).

Implement Standardized Training and Specialized Staffing

Dedicated resources must be allocated to ensure all staff involved in acute mental health triage possess the required core competencies, including specialized knowledge of psychopathology, risk assessment tools, and legal criteria. Policy must support staffing models that integrate dedicated mental health clinicians into the ED workflow, recognizing that their expertise is essential for high reliability and acts as a direct mechanism for reducing patient wait times, managing throughput, and mitigating ED volatility. Furthermore, training must explicitly focus on the detection and urgent management of high-acuity overlap syndromes, such as delirium and catatonia, requiring the immediate escalation of medical assessment for any new onset bizarre behavior.

Integrate Triage Scales with Disposition Planning

Triage instruments must be leveraged not solely as waiting-list prioritization tools, but as predictive models for disposition and resource allocation. Policy should encourage the use of scales that quantify non-clinical factors (e.g., support system, cooperation) early in the assessment process to facilitate rapid identification of patients suitable for community crisis diversion and to prioritize disposition planning for high-risk individuals requiring inpatient hospitalization. This strategy is key to mitigating the systemic barrier of ED boarding.

Foster Collaboration and System Linkage

Regulatory bodies must enforce regional collaboration among emergency medical services, law enforcement, and specialist mental health providers to develop consistent transport and referral guidelines. Clinicians must be provided with real-time access to mental health experts for tele-consultation, supporting confident and accurate triaging of complex cases and ensuring seamless connection to the necessary resources for follow-up and safety planning in the least restrictive environment.