Operationalizing International Disaster Response: Analysis of Cross-Border Triage Standards and Collaboration Mechanisms

The increasing frequency and complexity of Mass Casualty Incidents (MCIs)—driven by sudden-onset disasters such as earthquakes and floods, and complicated by complex humanitarian situations like refugee crises—have positioned transnational medical response as a necessity rather than an exception.

The increasing frequency and complexity of Mass Casualty Incidents (MCIs)—driven by sudden-onset disasters such as earthquakes and floods, and complicated by complex humanitarian situations like refugee crises—have positioned transnational medical response as a necessity rather than an exception.1 A successful MCI response fundamentally challenges routine clinical service delivery, requiring a shift in approach from ensuring the best possible outcome for each individual patient to the optimal allocation of scarce resources for the benefit of the population as a whole.3 This necessary transition—referred to as utilitarian triage—aims to identify and treat those who possess the highest potential for survival with available intervention, a core principle of Mass Casualty Management (MCM).3 Global organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO), have developed extensive resources and guidelines intended to enhance health sector capacity and assist policy makers and emergency managers in overcoming preparedness gaps.3

The Challenge of Geo-Political and Administrative Fragmentation

Despite existing global guidance, the operational deployment of MCI response across international boundaries is consistently hindered by geo-political and administrative fragmentation. Analysis of response dynamics in areas like Europe demonstrates that the long history of cooperation and conflict, compounded by varied environmental and governmental systems, results in inherent difficulties in coordination.1

A critical observation derived from cross-border response studies is that administrative and legal obstacles present the most serious impediment to efficient catastrophe response.1 These systemic barriers often exert a greater detrimental effect on operations and efficiency than cultural or language differences, although the latter remain statistically significant friction points.6 Overcoming these challenges requires not only technical standardization but also proactive policy alignment.

A pervasive ethical tension arises at the international border concerning the application of utilitarian triage versus adherence to humanitarian protection mandates. While WHO guidance explicitly defines MCI triage as a pragmatic, resource-driven calculation 3, formal cross-border evacuation protocols, such as those used in the Eastern Caribbean, simultaneously mandate the streamlined delivery of lifesaving response to all vulnerable persons, including women, children, the elderly, and persons with special needs.2 Policy frameworks must acknowledge this dichotomy and define precisely how strict mass triage principles—focused on saving the greatest number of lives—will interface with established standards requiring prioritization and protection for vulnerable groups who may require enhanced or specialized support before, during, and after evacuation.

Accelerating Preparedness through Policy Adoption

Policy mechanisms intended for disaster response often develop slowly. However, acceleration can be achieved by leveraging instruments already proven effective in non-emergency medical mobility. Many established cross-border healthcare initiatives, particularly within the European Union (EU), predate major disaster directives and were successfully built on the basis of routine patient movement.8 The EU’s Cross-border Healthcare Directive establishes mechanisms allowing patients the right to access health services in other EU/EEA countries and receive reimbursement for costs.9 These legal and logistical pathways, though focused on routine or elective care, provide a reliable foundation for rapid mobilization during a crisis.

Successful, routine collaborations offer tangible templates for emergency adoption. For instance, a collaboration between US and Mexican pediatric hospitals significantly improved clinical outcomes for Mexican pediatric leukemia patients by establishing a culturally sensitive partnership for specialized, planned care.11 This precedent demonstrates that establishing trusted, high-quality patient pathways for specialized services under normal conditions allows for the rapid adaptation of reimbursement structures and transfer logistics when a disaster mandates large-scale patient movement or medical aid. Therefore, disaster preparedness efforts should actively seek to borrow and adapt protocols designed for non-emergency medical mobility, utilizing these systems to build authorized, trusted pathways before a catastrophic event occurs.

Comparative Analysis of Multi-Jurisdictional Triage Standards

Effective cross-border response necessitates a shared understanding of patient prioritization. Currently, the landscape of triage systems is characterized by methodological diversity, creating significant potential for friction and misclassification when multiple international agencies converge on a mass casualty scene.

Civilian Field Triage Architectures: START, SALT, and the Core Criteria

The Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (START) system is the most widely recognized civilian framework for rapid assessment during a mass casualty incident. The system is designed for first responders to quickly delegate movement and prioritize victims using four main categories based on injury severity.12

START uses the rapid categorization of Respiration, Perfusion, and Mental Status (RPM) to assign patients:

BLACK (Deceased/Expectant): Injuries incompatible with life or absence of spontaneous respiration, even after airway opening attempts. These patients should not be moved forward.12

RED (Immediate): Severe injuries with high potential for survival if treated promptly. Criteria include a respiratory rate greater than 30, absent radial pulse (or capillary refill greater than 2 seconds), or inability to follow simple commands.12

YELLOW (Delayed): Serious injuries that are not immediately life-threatening.

GREEN (Walking Wounded): Minor injuries; identified by asking all victims who can walk to move to a designated area.

A refinement of START is the Sort, Assess, Life-saving Interventions, Treatment/Transport (SALT) system. SALT incorporates initial, time-non-intensive Life-Saving Interventions (LSI)—such as controlling major hemorrhage, opening airways, or administering auto-injector antidotes—during the assessment phase.12 The integration of LSI aims to improve initial stabilization before transport, and the system is valued for being easy to implement, accurate, and reliable, leading to its widespread application in disaster rescue.13

Despite the common goal of rapid classification 13, methodological diversity remains a major obstacle. Other recognized systems include the Field Triage Score (FTS), the Sequential Evaluation Method for MARCH, the Abbreviated Scoring Procedure Method for Combat Casualty (ASMcc) used by the Chinese military, and the CRAMS scale.13 ASMcc, for example, uses numerical scoring based on respiratory rate, systolic pressure, and the Glasgow Coma Index.13 This variety confirms that there is presently no single, universally adopted standard for MCI triage.13

Specialized and Strategic Triage Models (Military and CBRN)

In large-scale international disaster relief efforts, such as those seen in Haiti 14, military and specialized units (e.g., NATO forces) often participate, employing distinct triage protocols that must be reconciled with civilian standards.

The NATO T-Categories, derived from the Save a Life Everyday (SALE) system, are utilized in Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear (CBRN) environments. This system uses four tiers: T1 (Immediate), T2 (Delayed), T3 (Minimal), and T4 (Expectant).15 This specialized system explicitly integrates criteria relevant to hazard-specific exposure. For instance, a T1 designation includes those with critical injuries requiring LSI, those with an antidote indicated, or those with a high radiation dose ($> 2 \text{ Gy}$) combined with injury. Conversely, a T4 (Expectant) designation, intended for palliative care, is assigned to casualties with severe systemic disease or those with a dose exceeding $8 \text{ Gy}$.15 Crucially, the use of the T4 Expectant category requires authorization at a strategic policy level during a mass casualty incident.15

This distinction exposes a core challenge in cross-border coordination: a tactical mismatch in triage criteria, particularly regarding the most critical category. Civilian protocols often assign the Black/Expectant tag based purely on clinical assessment (e.g., apnea after airway opening).12 In contrast, the NATO T4 tag may be assigned based on specialized hazard exposure thresholds or requires explicit strategic authorization, demonstrating a policy overlay on the clinical assessment.15 When civilian and military medical units, or responders from different national systems, meet at a casualty collection point, a patient labeled T4 by a military unit may be misinterpreted by a civilian receiving hospital that adheres strictly to START/SALT criteria, potentially leading to resource misallocation or inappropriate denial of care. A formally documented crosswalk protocol, actively trained upon, is necessary to mitigate this tag confusion.

Furthermore, the status assigned to an MCI patient is fundamentally a resource-relative prediction, not an absolute clinical diagnosis. The foundational purpose of MCI triage is to manage care when resources are inadequate.3 This context means that a patient classified as Black/T4 in a resource-depleted requesting jurisdiction—where the prognosis is deemed incompatible with the treatment capacity—might be highly salvageable and classified as RED/T1 in a resource-rich receiving jurisdiction offering advanced trauma or surgical capabilities. Therefore, the triage status must be continuously communicated alongside real-time information regarding the resource capacity and availability of the receiving jurisdiction, addressing what can be termed the Utilitarian Threshold Paradox.

C. Standardization Efforts and the Quest for the "Gold Standard"

Efforts to standardize triage methodologies globally face a fundamental barrier: the lack of a defined gold standard against which the accuracy of triage categorization can be measured based on a patient's ultimate resource use.16 In the US, the Model Uniform Core Criteria (MUCC) was developed to standardize mass casualty triage and improve domestic interoperability.16 While essential for domestic efforts, achieving international consensus remains difficult due to inherent differences in resource allocation and policy objectives.

To evaluate the proper functioning of triage systems, accuracy is measured using indicators such as sensitivity, specificity, over-triage, and under-triage.4 When testing the implementation of data gathering models in cross-border MCIs, researchers employ statistical measures, such as the Kappa coefficient, to assess the inter-rater reliability and agreement of evaluations among different responding parties.18 Mandating the use of such rigorous statistical validation in future cross-border exercises is essential for ensuring methodological reliability.

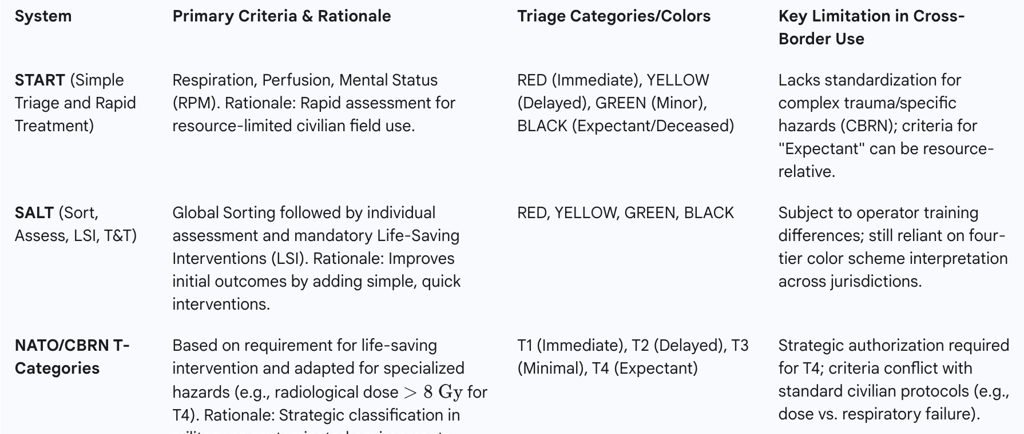

Table 1 details the comparison of primary international triage systems and their associated cross-border challenges.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Primary International Triage Systems

Collaboration Frameworks: Operationalizing Cross-Border Medical Assistance

Effective cross-border response is fundamentally dependent on the existence and activation of pre-established, formal legal and operational frameworks that govern the transfer of patients, personnel, and materiel.

Legal and Diplomatic Instruments: Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs)

In the context of cross-border emergency relief, Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) or regional ministerial declarations are vital instruments for formalizing and harmonizing inter-state efforts. These instruments provide the necessary structure to guide vulnerable persons safely and effectively across sovereign lines during a crisis. MOUs are critical for defining shared procedures, regulating population inflow and outflow, and standardizing the delivery of humanitarian and lifesaving responses.

International agreements for emergency assistance must establish clear definitions of key operational terms, such as the "requesting Party" and the "providing Party". A particularly crucial element of these agreements involves setting explicit procedures for the import and handling of essential medical resources, including narcotics and psychotropic substances. The protocols must mandate that rescue team leaders declare these controlled medications to the customs authorities of both the providing and requesting parties, indicating their nomenclature and amount, ensuring both medical necessity and legal compliance.

Mutual Aid and Incident Command Structures

Standardization of operational management is paramount when multiple jurisdictions and agencies (EMS, Red Cross, military) are involved. The use of common frameworks such as the Standardized Emergency Management System (SEMS) and the Incident Command System (ICS) is intended to provide a standard, scalable organizational structure. ICS is adaptable across different disciplines and can organize multi-casualty efforts into clearly defined functional units, such as a Medical group containing Triage and Treatment Units.

Mutual aid protocols, such as the Mutual Aid Box Alarm System (MABAS), establish a system of conditional criteria for initiating the response of external assets. Robust mutual aid agreements must cover practical and legal necessities, including addressing liability protection, defining communication channels, ensuring personnel safety, and detailing how the assisting agency will cover its home area while deployed elsewhere.

While established, formal agreements (MoUs, directives) provide the policy basis, the reliability of inter-facility patient transfer often depends on contractual or informal relationships developed between referral centers and community hospitals. However, in the setting of a major MCI, characterized by overwhelming resource demands , these informal arrangements—which rely on goodwill and established trust for day-to-day operations—are fragile and prone to collapse. Therefore, effective cross-border resilience requires that all critical operational elements, particularly concerning liability, customs clearance, and resource sharing, be elevated from informal agreements to legally binding, pre-authorized, and explicit protocols.

Regulatory Pathways for Patient Mobility and Transfer Logistics

Beyond disaster-specific MOUs, frameworks for routine patient mobility offer valuable logistical pathways. The EU Cross-border Healthcare Directive provides a foundation for patient rights, including access to care and cost assumption, encouraging Member States to develop shared protocols for patient and healthcare workforce mobility.

For immediate, critical care transfer, the process relies on formal transfer agreements that define the necessary steps for moving trauma patients between facilities, often within the regulatory context of stabilization requirements (such as EMTALA in the US). These agreements stipulate that the sending facility must notify the receiving facility as far in advance as possible, make every effort to stabilize the patient, transfer all personal effects and relevant information, and ensure that the receiving facility has available beds and resources.

A fundamental challenge arises when the medical imperative for timely care clashes with administrative logistics. Medical planning, as guided by NATO principles, requires that resuscitation and stabilization occur in a timely manner, with immediate life-saving interventions and emergency surgery provided "as far forward as possible". This principle directly conflicts with the fact that cross-border medical transport is notoriously slow, requiring time-consuming processes such as visa approvals, insurance validations, customs clearances, and air ambulance landing permissions. This administrative burden compromises the medical requirement for continuity of care and swift intervention. To reconcile the time-related constraints of medical care with standard border logistics, effective cross-border MOUs must include pre-approved "fast-track medical evacuation corridors" that suspend non-essential standard border checks for declared MCI patients and medical assets.

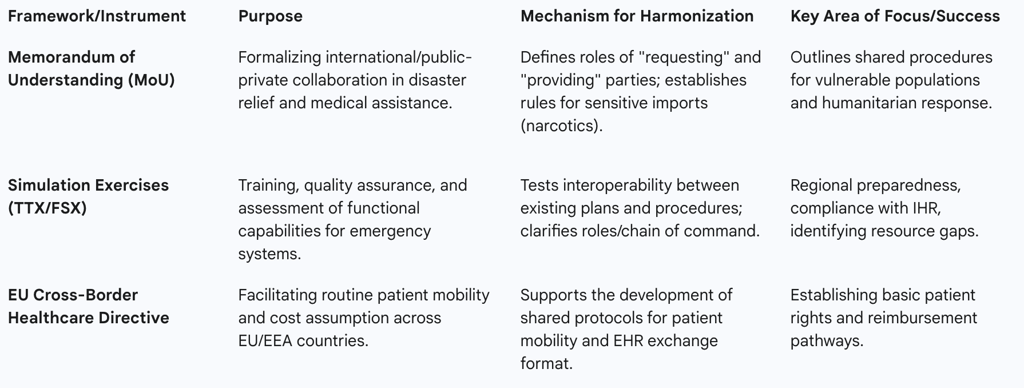

Table 3 summarizes the frameworks used to organize cross-border preparedness.

Table 3: Frameworks for Harmonizing Cross-Border Preparedness

Critical Barriers to Seamless Cross-Border Triage and Transfer

While the need for coordinated cross-border response is recognized, its successful implementation is undermined by systemic legal, informational, and operational barriers that require policy intervention beyond mere technical fixes.

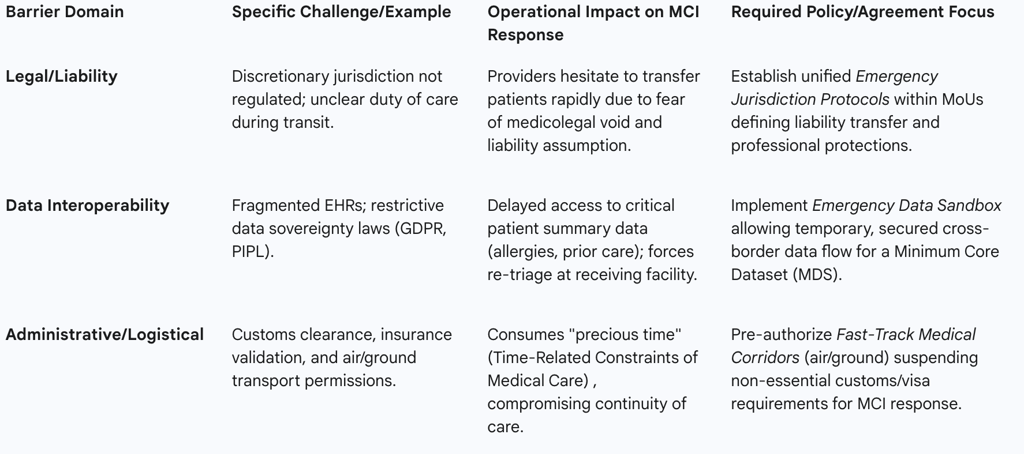

A. Legal and Medicolegal Liability Voids

One of the most profound challenges in regional emergency collaboration is the lack of clarity regarding legal liability. In established cross-border response systems, such as those operating across the Meuse-Rhine area (Belgium, Netherlands, Germany), the discretionary jurisdiction laws necessary to govern medicolegal cases are often not set or regulated, thereby creating a significant legal void.

This legal ambiguity is intensified during patient transfer. The exact point at which the sending hospital or jurisdiction legally relinquishes the duty of care and the receiving facility assumes responsibility is often unclear. This uncertainty about the allocation of responsibilities during consultation, stabilization, and transport creates substantial liability questions for all providers involved, often slowing down urgent medical transfers due to fear of medicolegal risk. Resolution of these legal boundaries is a non-negotiable component of liability protection for assisting agencies.

B. Data Interoperability and Sovereignty Constraints

Effective continuity of care is impossible without access to a patient’s medical history. However, global health systems are characterized by fragmented Electronic Health Records (EHRs) and EMR systems that are not typically designed to integrate data seamlessly from external or disparate sources. This fragmentation is exacerbated by cultural and linguistic differences, making it difficult to access personal health records for follow-up treatment upon returning home.

A critical regulatory challenge is the conflict between data security and survival. Global regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe, the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) in China, and similar laws in other countries impose strict constraints on how personal data, especially sensitive health information, can be collected, processed, and moved across jurisdictional borders. In some jurisdictions, the law takes a restrictive stance, explicitly prioritizing the value of security over the value of mobility.

While patients have a right to access and share their health data securely for emergency treatment abroad , the inability to legally and quickly move essential health information—such as a Patient Summary (PS) defined by implementation guides like epSOS—means receiving clinicians lack vital data (allergies, medications). The regulatory pursuit of data security, when executed without an explicit, legally defined emergency waiver mechanism, creates significant regulatory blowback risk and simultaneously compromises the physician’s fundamental ethical duty to provide competent and timely care, ultimately endangering patient safety.

Furthermore, while technical standards for interoperability exist (e.g., HL7 CDA, IHE profiles, and newer standards like HL7 FHIR) and are utilized in projects like the EU Patient Summary Guideline , simply mandating these technical specifications is insufficient. The persistence of interoperability issues, despite technical progress, indicates that the barrier is largely organizational, not solely technical. True transnational interoperability requires policy harmonization, cultural understanding, and organizational agreement on the meaning and context of shared clinical data, particularly the interpretation of triage categories and resource assumptions across different medical systems.

C. Operational, Administrative, and Linguistic Friction

Beyond the major legal and data concerns, day-to-day operational friction continues to impede response. Research into cross-border disaster response in Europe found that administrative and legislative obstacles are the most serious factor obstructing efficient catastrophe management. These obstacles include the complexity of financial and reimbursement issues related to the patient’s right to care abroad, which can slow down urgent medical transfers. Linguistic and cultural barriers also have a statistically significant detrimental effect on coordination efforts.

To summarize the operational impediments, Table 2 details the critical barriers and necessary policy responses.

Table 2: Critical Barriers to Cross-Border Patient Transfer and Policy Solutions

Policy Recommendations for Enhanced Cross-Border Resilience

The analysis reveals that enhancing cross-border resilience requires a multi-pronged approach focused on rigorous standardization, mandatory joint training, and the establishment of robust legal mechanisms that override jurisdictional friction during an emergency declaration.

Mandating Unified Triage and Reporting Standards

To address the issue of technical mismatch and ensure that triage status is universally understood, international partners must adopt a standardized approach for documenting patient status.

First, the adoption of a globally agreed-upon Minimum Core Dataset (MDS) is required for all MCI patients crossing borders. This MDS must include essential clinical and triage information—such as the assigned triage color, the patient’s age band, and a record of any Life-Saving Interventions performed—using harmonized alphanumeric formats to combat data segmentation and support electronic data collection. Post-event analysis, utilizing statistical measures like the Kappa coefficient, must be mandated to rigorously test the degree of agreement and operational reliability of this MDS in real-world or simulated cross-border MCIs.

Second, multilateral agreements should pursue consensus on a standardized triage methodology, potentially adopting the core principles of systems like MUCC or establishing a formal, codified crosswalk protocol between standard civilian frameworks (START/SALT) and military/specialized systems (NATO T-Categories). This consensus is vital to eliminate ambiguity, particularly surrounding the interpretation and treatment protocols for the "Expectant" (Black/T4) category.

Enhancing Preparedness Through Joint Training and Simulation

The theoretical existence of protocols is insufficient; their functional interoperability must be rigorously tested under stress. Joint, cross-border simulation exercises (SIMEX) are the primary mechanism for assessing and testing the effectiveness of operational plans, guidelines, and Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) across jurisdictions.

Policy should mandate the regular implementation of both Table Top Exercises (TTX) and Full-Scale Field Simulation Exercises (FSX), particularly those focusing on complex scenarios (e.g., the One Health approach targeting zoonotic outbreaks, as conducted between Kenya and Tanzania). These exercises must focus explicitly on clarifying roles and responsibilities, practicing the chain of command, and improving coordination to reveal planning weaknesses and resource gaps that cannot be identified on paper. Furthermore, the incorporation of advanced tools, such as GIS mapping and digitized, AI-enhanced simulation training, can improve the learning experience and the perception of preparedness for complex MCIs.

Establishing Legal and Regulatory Sandboxes for Emergency Response

Since administrative and legislative obstacles are the most serious impediments to efficient cross-border response , policy efforts must focus on unifying legal frameworks and streamlining administrative processes. This means shifting the paradigm from merely ensuring compliance with existing, often conflicting, rules (e.g., IHR or GDPR) to establishing a resilient legal architecture that can anticipate and override fragmentation when a crisis is declared.

Emergency Data Sovereignty Waiver: International protocols must be developed to establish a pre-authorized "safe harbor" or regulatory sandbox for data exchange during a declared MCI. This mechanism would allow for the temporary and secured suspension or streamlining of strict data privacy restrictions (such as GDPR or PIPL) solely for the purpose of rapidly sharing the Minimum Core Dataset necessary for patient continuity of care. This addresses the critical tension between data security and patient survival.

Discretionary Jurisdiction Resolution: Binding legal protocols must be integrated into MOUs to clearly define the transfer of legal liability, professional protection for responding personnel, and the application of discretionary jurisdiction during patient transport between the requesting and providing parties. This ensures personnel safety and removes the legal void that causes operational hesitation.

Cross-Sectoral Vulnerability Triage: Harmonization efforts must extend beyond technical triage protocols to a unified, shared methodology for assessing and communicating multi-hazards and vulnerabilities. Projects that focus on harmonized cross-border risk assessment (e.g., seismic and hydro-meteorological hazards, as with the BORIS project) provide the foundational data necessary. Establishing this shared framework allows strategic resource stockpiles and aid to be mobilized rapidly, justified by commonly understood cross-border vulnerability maps, thereby integrating health and civil protection objectives.

By prioritizing the development of pre-authorized legal solutions that streamline operational logistics and overcome restrictive data sovereignty boundaries, international collaboration can move toward a system capable of executing rapid, standardized, and legally secure cross-border triage and patient transfer during catastrophic events.