Comparative Analysis of Military and Civilian Triage Systems

The systematic interpretation of triage principles was later translated to the civilian sector, beginning with its implementation in hospital emergency departments (EDs) in 1964. The historical trajectory reveals that the most impactful lessons regarding trauma care often originate from battlefield necessities, leading to fundamental advancements in civilian practice.

Triage, a term derived from the French word trier, meaning "to sort or choose," is a critical medical process utilized to categorize patients based on injury severity and prioritize care and monitoring when demands exceed available resources. The practice of triage has deep military origins, dating back to the 18th century, with systematic implementation credited to French military surgeon Baron Dominique Jean Larrey during the Napoleonic Wars. Larrey’s system focused on the rapid evaluation and categorization of wounded soldiers to identify those whose survival likelihood could be improved by timely surgical intervention.

The systematic interpretation of triage principles was later translated to the civilian sector, beginning with its implementation in hospital emergency departments (EDs) in 1964. The historical trajectory reveals that the most impactful lessons regarding trauma care often originate from battlefield necessities, leading to fundamental advancements in civilian practice. For instance, the establishment of regionalized civilian trauma systems, emphasizing the swift transport of the "right patient to the right place at the right time," emerged directly from lessons learned during United States armed conflicts. This evolution confirms that triage, in all its forms, is fundamentally a resource-constrained management tool. The severity and nature of the operational constraint—be it surgical capacity on a remote island or staffing shortages in an urban ED—ultimately dictates the complexity of the triage protocol and the ethical decisions required.

Defining the Core Mission: Patient vs. Operation

The most profound philosophical divergence between military and civilian triage is the definition of the mission itself. In the civilian setting, the patient’s well-being and maximization of individual outcome serve as the singular mission. Civilian clinical guidelines and emergency medical decision-making are rooted in minimizing uncertainty and risk. For example, clinical practice guidelines often aim for a high margin of certainty, approximately 98 percent, before discharging a patient, ensuring the absence of a time-sensitive, life-threatening condition.

In contrast, military triage is inextricably nested within a broader tactical and operational context. Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) doctrine mandates a tripartite goal set that supersedes the individual patient: 1. Treat the casualty, 2. Prevent further casualties (force protection), and 3. Complete the mission. This requirement fundamentally alters the calculus of medical decision-making.

When operating in environments characterized by prolonged engagements, multidimensional threats, and severe resource competition—such as in Large-Scale Combat Operations (LSCO)—medical providers must alter their decision-making algorithms to tolerate higher degrees of uncertainty regarding individual patient prognosis. This necessity stems from the increasing operational risk associated with sustained combat. When operational priorities demand the efficient use of limited resources, medical providers must accept a greater margin of risk for the individual patient to ensure the force remains mission-capable. This acceptance of elevated individual medical risk represents a strategic shift away from absolute individual beneficence toward a collective utilitarian model, influencing every aspect of logistical and clinical planning, including decisions regarding resource denial for high-consumer casualties.

Civilian Triage Methodologies: Focus on Maximizing Individual Outcome

Civilian triage systems are employed in two distinct settings: the structured, relatively resource-rich environment of the Emergency Department (ED), and the chaotic, resource-depleted environment of a Mass Casualty Incident (MCI).

Emergency Department (ED) Triage: Acuity, Flow, and Resource Management

The primary objective of ED triage is to rapidly categorize patients based on acuity and anticipated resource needs to optimize patient flow, ensure timely care, and improve overall outcomes.

The Emergency Severity Index (ESI)

The Emergency Severity Index (ESI) is the dominant system in the U.S., utilized by approximately 94 percent of hospitals. The ESI algorithm rapidly and reproducibly stratifies patients into five levels, from Level 1 (most urgent) to Level 5 (least urgent). ESI distinguishes patients not only by the urgency of their condition (imminent threat to life or organ) but also by the predicted utilization of hospital resources. This emphasis on resource integration means that ESI is used to manage hospital workflow, identifying high-acuity patients who need immediate physician attention and high-consumer patients who might require extensive lab work, imaging, and consultations, thereby preparing the internal hospital logistics. The use of ESI and similar tools, such as the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS), allows for accurate prioritization and effective utilization of space and resources. For instance, Prehospital CTAS assists EDs in preparing internal resources for patients arriving via ambulance.

The fundamental purpose of these hospital-based systems is resource expectation and preparation—predicting and managing internal strain—rather than anticipating and mitigating resource denial due to external operational failure, a constraint that heavily characterizes military medicine.

Mass Casualty Incident (MCI) Triage Systems

When faced with an incident overwhelming local capabilities, civilian first responders rely on streamlined sorting tools.

Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (START)

The START (Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment) system was developed in 1983 and is intended for rapid deployment by lightly trained personnel. The system uses four main categories: Immediate (Red), Delayed (Yellow), Minimal (Green, or "walking wounded"), and Expectant/Deceased (Black). The process involves asking all victims who can walk to move to a designated area, immediately assigning them the Minimal category. Non-ambulatory patients are then assessed based on Respiration, Perfusion, and Mental Status (R-P-M). Red tags are assigned to patients demonstrating respiratory rates greater than 30, absent radial pulse (or capillary refill greater than 2 seconds), or those unable to follow simple commands.

SALT Triage

The SALT (Sort, Assess, Life-saving Interventions, Treatment/Transport) system was developed as a standardized, national guide for mass casualty triage. SALT aims to unify the process by incorporating key steps, including performing immediate Life-saving Interventions (LSIs) like hemorrhage control, during the assessment phase. This inclusion reflects a key recognition: while START prioritizes rapid sorting based on respiration, modern high-threat environments necessitate the immediate treatment of catastrophic hemorrhage.

There is a structural conflict between the established START system and the clinical priorities necessitated by modern trauma mechanisms. Because START prioritizes rapid categorization, an ambulatory patient with catastrophic, rapid exsanguination might be initially classified as Minimal ("Green") if they are able to walk, potentially delaying definitive, life-saving hemorrhage control. This methodology reflects a priority of mass sorting over immediate, targeted life-threat management. Modern adaptations, such as SALT and Tactical Emergency Casualty Care (TECC), attempt to mitigate this by inserting aggressive LSI, drawing lessons directly from combat care.

Military Triage Doctrine: Tactical Context and Phased Care

Military triage is distinguished by its direct integration with tactical operations, demanding protocols that prioritize mission effectiveness alongside casualty survival, particularly under hostile conditions.

Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) Framework

TCCC has become the Department of Defense’s standard of care for tactical management of combat casualties, endorsed by both the American College of Surgeons and the National Association of EMTs. TCCC's core principle is to avoid preventable deaths by combining "good medicine with good tactics". Triage in the combat environment is dynamic, governed by three operational phases :

Care Under Fire (CUF): Care delivered while the medic and casualty are under effective hostile fire. The tactical imperative is paramount; providers must remain engaged with perpetrators or establish fire superiority. Medical care is severely limited to immediate, life-saving hemorrhage control, typically utilizing only materials carried by the operator, such as a limb tourniquet.

Tactical Field Care (TFC): Care delivered once the threat is mitigated and the casualty is protected. Resources are still limited, and time to evacuation may range from minutes to hours. This is the phase where formal triage decisions are made using the MARCH algorithm.

Tactical Evacuation Care (TACEVAC): Care rendered during transport to a definitive care facility.

The MARCH Algorithm

The cornerstone of TCCC patient assessment in TFC is the sequential MARCH algorithm :

M – Massive Hemorrhage: Prioritized control of all life-threatening bleeding using CoTCCC-recommended limb or junctional tourniquets or hemostatic dressings.

A – Airway: Assessment and management, including basic or surgical airway interventions.

R – Respiration: Assessment and treatment of respiratory trauma, such as tension pneumothorax or sucking chest wounds.

C – Circulation: Assessment for shock and other circulatory compromise.

H – Head injury / Hypothermia: Assessment of head trauma, management of altered mental status, and prevention of hypothermia.

The immediate prioritization of Massive Hemorrhage (M) over Airway (A) distinguishes the TCCC algorithm most significantly from traditional civilian protocols (ABCs). This clinical divergence is a direct response to combat fatality data, which indicate that nearly 50 percent of combat deaths since World War II were due to exsanguinating hemorrhage, half of which were potentially preventable with timely care. The doctrine dictates that securing an airway is ineffective if the patient rapidly succumbs to uncontrolled bleeding, emphasizing the unique pattern of high-velocity, high-trauma injuries seen on the battlefield.

Triage in Prolonged Casualty Care (PCC) and Large-Scale Combat Operations (LSCO)

As military operations increasingly encounter prolonged evacuation times and severely limited resources, the demands on triage grow exponentially. Prolonged Casualty Care (PCC) is defined as field medical care applied beyond doctrinal timelines, requiring medics to stabilize patients for extended periods.

Resource-Constrained Triage

A Mass Casualty (MASCAL) event in a PCC environment presents unique and dynamic triage challenges, primarily the low likelihood of receiving additional medical supplies or enhanced capabilities. Triage decision-making must first determine if the requirements for care exceed the available capabilities. This environment necessitates a move toward more conservative resource allocation than traditional MASCAL in mature theaters where definitive care and resupply are more readily available.

Situational Triage

For future Large-Scale Combat Operations (LSCO), characterized by prolonged engagements and restricted movement, a new concept, "situational triage," is necessary. Situational triage is an operations-centric, resource-conscious framework that requires medical decisions to incorporate the commander's priorities and logistical constraints. This approach is significantly more complex than conventional triage because it concentrates on apportioning scarce resources to specific interventions most likely to result in a meaningful effect on the desired operational end state.

This framework ensures cohesion between operational and medical priorities by clarifying necessary adjustments to medical risk tolerance. For example, medical leaders must gauge the value of placing surgical assets far-forward, knowing that a mission-capable medical element is a theater asset, while a culminated, resource-depleted unit is a command liability. Situational triage ensures that medical decisions actively prevent the forward medical element from reaching culmination before the operational end state is achieved, necessitating the structured denial of resources to high-consumer casualties.

Differential Triage Categories and Time Sensitivity

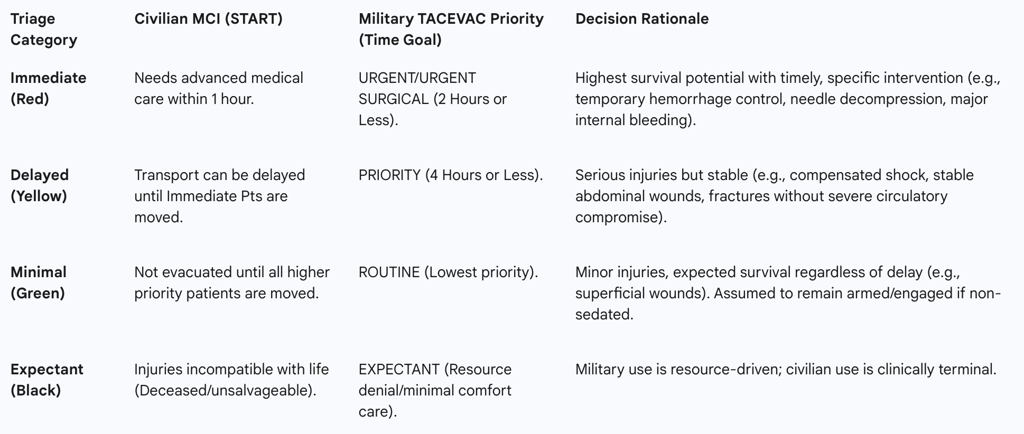

Both military and civilian disaster systems utilize the standard four categories (Immediate, Delayed, Minimal, Expectant), but the clinical criteria and logistical implications of these categories—particularly the "Expectant" status—differ sharply.

Standard Triage Categories (Immediate, Delayed, Minimal)

The time sensitivity for evacuation (TACEVAC) clearly differentiates military prioritization. Military medical evacuation (MEDEVAC) categories often feature shorter, time-bound goals (Urgent: 2 hours or less; Priority: 4 hours or less) for patients who have received initial life-saving measures like tourniquets or needle decompression. In contrast, civilian MCI evacuation priorities (Red, Yellow, Green) primarily sequence transport relative to the patient population, rather than adherence to strict, operationally constrained time limits for definitive care.

The Critical Distinction: The Expectant Category (Black)

The classification of casualties as Expectant (Black tag) serves as the clearest doctrinal and ethical demarcation point between military and civilian triage practices.

In civilian MCI doctrine (like START), the Expectant category is typically a clinical declaration applied to individuals with grave injuries deemed incompatible with life, such as those who are apneic even after attempts to open the airway. This classification implies clinical futility—the patient is expected to die regardless of intervention given the circumstances. While the category exists for extreme situations like Chemical, Biological, Radiological, or Nuclear (CBRN) mass casualty incidents, the underlying assumption in peacetime is that all patients have a chance of survival, and resources should ideally be allocated accordingly.

Conversely, in the military context, particularly under LSCO or Prolonged Casualty Care (PCC), the Expectant category is explicitly defined by logistical realities. The military designation is used only in combat operations or MASCAL situations where the requirements to adequately treat these patients exceed the available resources. A casualty may still be clinically salvageable, but if treating them requires such extensive resources—time, blood products, or surgical capacity—that it would prevent the medical team from saving a greater number of other viable casualties, the patient is designated Expectant. Therefore, the military Expectant tag represents a logistical declaration and a mandated act of resource rationing driven by utilitarian principles, rather than a mere declaration of clinical failure.

Operational Constraints and Resource Allocation Modeling

The austere and hostile operational environment fundamentally dictates the methodology of military triage, compelling the prioritization of resource preservation and operational security (OPSEC).

Evacuation Time and Definitive Care

Civilian trauma care is predicated on a functioning regionalized system designed to minimize the time between injury and definitive care. This reliance assumes a functional continuum of care from the scene to the hospital.

Military medical care, particularly in far-forward or isolated areas, operates under the assumption of a broken continuum, characterized by the potential for long evacuation delays that can last hours or even days. This logistical breach forces forward medical providers (Role 1 care) to perform prolonged casualty care (PCC), stabilizing patients for extended periods using limited supplies. TACEVAC decisions must therefore be determined by the tactical situation, the available Casualty Collection Points (CCPs), and the unit’s overall operational location, demanding that the medical provider act as a primary decision maker for treatment and evacuation tasks.

Logistical Scarcity: Triage as a Resource Management Tool

In resource-constrained environments, triage decisions cannot be based solely on immediate tactical or medical conditions. Military triage models must classify casualties not just by injury severity but by projected resource consumption. Casualties are categorized based on whether they require few or many scarce resources, or a small or large total volume of resources.

The rationale for situational triage is centered on preventing a single, resource-intensive casualty from depleting supplies, thus rendering the medical unit incapable of treating future casualties. This necessitates a complex decision framework that systematically assesses and addresses the high likelihood that combat injuries will outpace available resources. This structural need requires the quantification of utilitarian principles, transforming resource rationing into an actionable decision framework that balances manpower sustainment against resource requirements.

Operational Security and Communication

Operational Security (OPSEC) requirements impose another critical layer of complexity on military triage that is absent in civilian settings. The need for strict OPSEC can significantly hinder timely communication with the command operation center (COC) regarding critical information, such as immediate resupply status or required movement. Without accurate, up-to-date logistical data, medical providers’ ability to make complex triage decisions—particularly regarding the viability of treatment versus resource preservation—is severely compromised.

To mitigate this, modern military medical planning is integrating technology (e.g., Tactical Assault Kit, or TAK) to provide secure, real-time tracking of casualties and surgical assets. This capability allows medical leaders to physically track casualties and plan resource allocation based on the distance to required surgical capability, enabling objective (though still difficult) resource-denial decisions. The ability to transmit granular data with enhanced security helps nest medical logistical planning within the commander's intent.

Ethical Frameworks, Moral Dilemmas, and Provider Resilience

The Utilitarian Mandate: "Greatest Good for the Greatest Number"

The historical foundation of triage, originating with Larrey, is rooted in classical utilitarian principles. Utilitarianism dictates that medical resources should be directed where they will yield the greatest overall benefit, meaning individual patient interests may be overridden to maximize collective survival. In the military context, this utilitarian ethic is formalized in the doctrine of situational triage, which subordinates conventional individual medical prioritization to the requirements of the mission.

While abstract ethical principles such as beneficence (doing good for the individual), justice, and fidelity remain aspirations, their practical application must be relative to the immediate situation and resource availability. The military environment introduces an additional ethical layer: the issue of "nation-aware triage". While civilian medical ethics strictly prohibit treating a patient based on non-medical factors like nationality, military environments, particularly those facing extreme resource scarcity, may permit prioritizing a compatriot soldier over an enemy combatant. This introduces national identity as a legitimate, non-clinical variable into the utilitarian calculation, a concept profoundly antithetical to civilian medical doctrine.

The Impact of Triage Decisions on Provider Mental Health (Moral Injury)

The necessity of making life-and-death decisions under extreme constraint, particularly those involving resource denial, generates significant ethical challenges and moral distress for clinicians.

Moral injury (MI) is the psychological, cognitive, and emotional impact of participating in or witnessing a highly stressful event that transgresses one's core moral beliefs. This phenomenon has been studied extensively in combat veterans but is also increasingly recognized among civilian healthcare workers (HCPs) who faced resource scarcity and rationing dilemmas during events like the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, military healthcare personnel face unique compounding factors, including dual obligations to patient care and national security requirements, coupled with hierarchical decision-making structures. The requirement in LSCO to designate a patient as Expectant based purely on logistical grounds (knowing they might be saved otherwise) places an immense burden of moral distress. This mandated ethical failure, essential for mission viability, results in elevated MI risk and specific psychosocial outcomes like persistent guilt. The difficulty and emotional toll of military triage are acknowledged within the doctrine itself, requiring proactive measures and training to minimize the effects on medical teams.

Cross-System Adaptation and Recommendations

The operational lessons learned from military conflicts have consistently informed and improved civilian trauma care, particularly in high-threat scenarios.

Military Lessons Applied to Civilian High-Threat Environments

The necessity of rapid, effective trauma care on the battlefield led to the maturation of TCCC, which focused intensely on preventable death through hemorrhage control. Recognizing the commonalities between combat injuries and those resulting from civilian tactical incidents (e.g., active shooters), the Committee for Tactical Emergency Casualty Care (C-TECC) adapted TCCC principles into the Tactical Emergency Casualty Care (TECC) guidelines.

TECC provides specific guidelines for civilian first responders (law enforcement, EMS) operating in austere, dynamic, and resource-limited environments. This transition was strongly supported by the Hartford Consensus, which mobilized the American College of Surgeons to drive policy focused singularly on hemorrhage control, advocating for the widespread use of tourniquets and hemostatic agents as the standard of care in high-threat environments. In essence, when civilian operational constraints (inaccessibility due to threat) and mechanisms of injury (high-velocity trauma) mimic combat, civilian doctrine functionally shifts to adopt TCCC’s priorities and techniques, proving that hemorrhage control must be paramount when definitive care is delayed.

Recommendations for Interoperability and Standardized Doctrine

The continued evolution of triage across both military and civilian sectors requires proactive planning and integration:

Standardized High-Threat Training: Continued integration and standardization of TCCC-derived protocols (TECC) across civilian EMS and law enforcement agencies are essential to decrease preventable deaths in tactical and mass casualty incidents.

Proactive Ethical Preparedness: Given that acute mass casualty events, once relegated primarily to the battlefield, are recurring in civilian communities (e.g., terrorist attacks), both military and civilian health systems must proactively address the ethical concerns of triage and rationing through education, training, and policy review.

Data and Lesson Sharing: To refine protocols, particularly those concerning rare events such as CBRN incidents, nations and health sectors must share best practices and lessons learned, subject to appropriate security and legal constraints.

Conclusion

The comparison of military and civilian triage systems reveals a fundamental divergence driven by distinct operational mandates. Civilian triage (whether ED-based or MCI-driven) prioritizes the individual patient outcome, utilizing algorithms like ESI and START/SALT primarily for resource prediction and flow management, adhering largely to the principles of beneficence and justice. In contrast, military triage, embodied by TCCC and the emerging doctrine of Situational Triage for LSCO, prioritizes the mission, force preservation, and collective good, operating strictly under a resource-driven utilitarian ethic.

The clearest manifestation of this divergence lies in the Expectant (Black) triage category. In civilian practice, Expectant is a clinical pronouncement of futility; in military LSCO, it becomes a crucial logistical declaration—the mandated denial of scarce resources to high-consumer casualties to preserve the medical capability required to save the greater number of mission-critical personnel. This doctrinal necessity ensures force readiness but imposes a significant burden of moral injury upon medical providers, highlighting the extreme ethical cost inherent in adapting medical practice to the operational reality of sustained, resource-constrained combat. The successful cross-pollination of TCCC principles into the civilian high-threat environment through TECC and the Hartford Consensus demonstrates that while core missions differ, the focus on rapid, targeted hemorrhage control remains the universal key to mitigating preventable trauma death when timely definitive care cannot be guaranteed.