Analysis of Emergency Department Triage Systems, Clinical Risk Stratification, and Operational Efficacy

When a patient arrives at the Emergency Department (ED) without ambulance transport, the triage process is the first step in care. Triage is the initial assessment that determines the severity of the patient's condition. This assessment precedes subsequent phases of the overall care journey, which include Registration, Treatment, Reevaluation, and eventual Discharge.

The practice of triage is foundational to emergency medicine, originating from the French word "trier," meaning to sort or organize. This systematic approach is utilized globally in healthcare to categorize patients based on the severity of their injuries or illnesses, thereby establishing the necessary order and speed of monitoring and care.

The history of emergency triage is rooted deeply in military field medicine. Documentation dating back to the 18th century shows how field surgeons would rapidly assess soldiers to determine if immediate intervention was feasible. The concept was notably formalized by French military surgeon Baron Dominique Jean Larrey, the chief surgeon in Napoleon Bonaparte’s imperial guard, who developed a structured system for quickly evaluating and categorizing wounded soldiers during battle. This early military application established a crucial ethical principle: resource optimization and prioritization when resources (surgeons, time, supplies) are critically limited.

The adoption of this military system into civilian healthcare marked a significant turning point. The triage system was first formally implemented in hospital emergency departments (EDs) in 1964, following the systematic interpretation published by Weinerman et al.. This adoption demonstrates that triage, even in civilian settings, is fundamentally a tool for managing resource scarcity and optimizing operational flow in high-demand environments. Modern triage is now integrated across three phases: prehospital triage, triage at the scene (especially during mass casualty incidents), and triage upon arrival to the ED.

1.2. Defining the Triage Imperative: Core Objectives

The primary objective of triage is straightforward: to assess patients rapidly and categorize them according to their need for immediate care, thereby prioritizing the sequence of treatment delivery. However, the universal goal of modern triage systems extends beyond simple sorting; it is to supply effective and prioritized care to patients while simultaneously optimizing resource usage and timing.

This function transforms triage into a sophisticated mechanism of clinical risk management. Rather than merely managing a waiting line, the process is designed as a rapid sorting system that quickly identifies patients presenting with a "potential for demise" resulting from an injury or illness. This rapid identification is essential for patient safety, as it dictates patient flow, helps minimize overall wait times for necessary interventions, and ultimately prevents adverse outcomes associated with delayed diagnosis or treatment. The effectiveness and validity of any triage system, therefore, are measured not just by its accuracy but by its contribution to streamlined ED operations and the judicious application of limited resources.

1.3. The Triage Professional: Role, Competencies, and Legal Framework

Triage is typically performed by a specialized triage nurse or experienced Registered Nurse (RN). This role demands extensive clinical competence, requiring critical thinking and adherence to standardized guidelines. Educational requirements usually include an Associate Degree in Nursing (ADN) or a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN), followed by obtaining an RN license and gaining substantial experience, often in acute care or emergency settings.

Specific professional certifications are often required, including Basic Life Support (BLS), and frequently, Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS) or Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS). The Trauma Nursing Core Course (TNCC) certification is also highly valued, especially in emergency departments handling significant trauma volume.

The triage nurse, by assigning an acuity score and corresponding expected wait time, functions as the principal operational gatekeeper and initial risk assessor for the entire ED. This crucial function mandates objective decision-making, requiring the nurse to approach the patient without clinical or personal bias to ensure proper prioritization and treatment access. Given that inaccurate triage can directly lead to increased morbidity and mortality , this role involves substantial legal and ethical responsibility, necessitating not only deep clinical knowledge but also a thorough understanding of hospital flow and resource constraints.

The Workflow of Triage in the Modern Emergency Department

2.1. The Step-by-Step Triage Process

When a patient arrives at the Emergency Department (ED) without ambulance transport, the triage process is the first step in care. Triage is the initial assessment that determines the severity of the patient's condition. This assessment precedes subsequent phases of the overall care journey, which include Registration, Treatment, Reevaluation, and eventual Discharge.

The triage assessment is designed to be extremely rapid. In the context of a mass casualty incident (MCI), the assessment must take 30 seconds or less. For non-emergent pediatric cases, the assessment averages approximately twenty seconds. During this brief encounter, the triage nurse gathers essential information, including the chief complaint, current symptoms, relevant medical history, and current medications.

It is fundamental to modern triage that the process is not static. It is a highly dynamic system. If a patient's symptoms worsen, or if vital signs begin to deteriorate while they are waiting for treatment, they must immediately inform the triage staff. This requires a rapid reassessment (re-triage) and the assignment of a new, higher priority level, ensuring that declining patients are quickly streamed back toward immediate care.

2.2. Critical Assessment Components: The Rapid Physical Examination (ABCDE)

The triage assessment relies on standardized, focused physical assessment protocols to quickly identify immediate threats to life. These protocols, such as the pediatric ABCD (Airway, Breathing, Circulation/Coma/Convulsion, Dehydration) , prioritize the immediate physiological status of the patient. The assessment focuses heavily on the basic parameters of A-B-C:

Airway: Assessment focuses on whether the airway is patent or impaired. Signs of impairment requiring immediate attention include stridor, hoarseness, drooling, or facial/oropharyngeal edema.

Breathing: The nurse observes for unlabored versus labored breathing. Indicators of severe respiratory distress include the use of accessory muscles, retractions, or nasal flaring. A child who is smiling or crying, for example, is generally considered not to have severe respiratory distress.

Circulation: Assessment involves checking for obvious bleeding, evaluating skin color (e.g., pallor, cyanosis) and moisture (e.g., diaphoretic), and assessing pulse rate (fast or slow) and rhythm.

This rapid ABC assessment serves not as a diagnostic phase, but rather as a highly effective failure mode identifier. By quickly evaluating these three core physiological functions, the triage professional flags the patient who is actively or imminently collapsing. Any significant deficit in A, B, or C indicates a time-critical problem. Such a finding immediately mandates a Level 1 or Level 2 priority, regardless of the patient's stated chief complaint or diagnosis, because physiological failure is the most urgent risk.

2.3. Objective Metrics: Vital Signs and Level of Consciousness Scoring

Objective metrics are crucial for assigning an acuity score reliably. Measured vital signs typically include body temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and a subjective pain score.

Evaluating the Level of Consciousness (LOC) is paramount, particularly in cases of trauma or sudden clinical changes. The AVPU scale (Alert, Verbal, Pain, Unresponsive) is commonly used to rapidly determine neurological status. Patients who are only responsive to painful stimuli (P) or are completely unresponsive (U) are categorically triaged as Level 1, requiring immediate intervention.

For a more detailed neurological assessment, particularly in higher acuity systems, the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is used. An unconscious state, an inability to protect the airway, continuous seizure activity, or progressive deterioration in LOC, corresponding to a GCS score of 3–9, automatically places the patient in Level 1 (Resuscitation). An "altered level of consciousness," defined as a GCS score between 10 and 13, including new onset confusion, agitation, or loss of orientation, mandates assignment to Level 2 (Emergent) care.

Furthermore, unstable vital signs, particularly those approaching dangerous limits, automatically elevate the triage level to Level 2. It is critical that these dangerous vital sign thresholds are adjusted according to age, preventing critical under-triage in both pediatric and geriatric populations.

Standardized Multi-Level Triage Systems

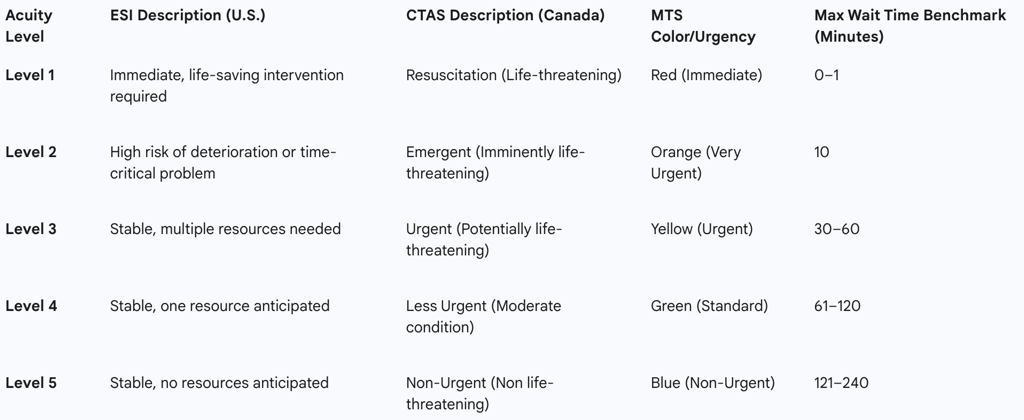

In modern emergency care, the use of standardized, five-level acuity scales is essential for achieving consistency and comparability in clinical risk stratification across different institutions. These systems categorize urgency by blending clinical assessment with anticipated resource needs.

3.1. The Emergency Severity Index (ESI): Acuity versus Resource Utilization (U.S.)

The Emergency Severity Index (ESI) is a commonly used five-level triage algorithm in the United States, initially developed in 1998. Currently maintained by the Emergency Nurses Association (ENA), ESI is structured around four key decision points that combine the assessment of immediate clinical acuity (likelihood of life or organ threat) with the triage nurse’s prediction of the resources needed to treat the patient.

Level 1 (Immediate): Reserved for patients requiring immediate, life-saving intervention without delay. Examples include cardiac arrest, profound hypotension, or unresponsiveness.

Level 2 (Emergent): Assigned to patients at high risk of rapid deterioration or exhibiting signs of a time-critical problem. Examples include altered mental status or cardiac-related chest pain.

Levels 3-5 (Resource-Based): For stable patients, the level is determined primarily by the anticipated number of resources required for diagnosis and treatment:

Level 3 (Urgent): Stable, but the patient is predicted to require multiple types of resources (e.g., laboratory tests plus diagnostic imaging).

Level 4 (Less Urgent): Stable, predicted to require only one type of resource (e.g., only an x-ray, or only simple sutures).

Level 5 (Non-Urgent): Stable, requiring no resources beyond basic oral or topical medications, or a prescription refill.

3.2. The Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS): Comprehensive Assessment Modifiers (Canada)

The Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) is a standardized five-level system implemented nationally in Canada since 1999. The goal of CTAS is to support valid acuity scoring across a broad range of emergency presentations, including major trauma, cardiovascular complaints, and mental health issues.

The CTAS levels are defined as: Level 1—Resuscitation, Level 2—Emergent, Level 3—Urgent, Level 4—Less Urgent, and Level 5—Non-Urgent. CTAS utilizes physiological and non-physiological "modifiers" to refine the acuity score beyond the initial presenting complaint, thereby improving the accuracy and reliability of the system in predicting resource needs and ensuring appropriate care.

3.3. The Manchester Triage System (MTS) and Global Variations

The Manchester Triage System (MTS) is another globally implemented tool for clinical risk management. MTS uses color-coded urgency categories linked to fixed time windows for physician contact. This system relies on assessing the patient's presentation and symptoms, which are associated with predetermined urgency levels based on the likelihood of risk to the patient.

The MTS categories and corresponding urgency levels are:

Red (Immediate): Represents the highest priority, reserved for life-threatening cases requiring immediate intervention.

Orange (Very Urgent): For high-risk conditions, requiring treatment within 10 minutes of presentation.

Yellow (Urgent): For serious cases that are not immediately life-threatening but have the potential to become more serious, requiring treatment within 60 minutes.

Green (Standard): For non life-threatening cases that still require timely treatment.

Blue (Non-Urgent): For minor conditions.

The assessment is performed ideally before patient administration, leading to the allocation of a time window within which the first physician contact should occur.

3.4. The Critical Relationship between Triage Level and Time-to-Treatment Benchmarks

The assigned triage level represents a critical operational benchmark, functioning as a contract for the maximum acceptable waiting time until the patient receives initial treatment or is seen by a clinician. Adherence to these time benchmarks is crucial for patient safety and institutional performance assessment.

The generalized recommended benchmarks for five-level systems are:

Table 1: Comparison of Major Five-Level Acuity Scales and Time Benchmarks

The disparity between these target benchmarks and the operational reality of many overcrowded EDs highlights a critical source of ethical strain. While the system promises prioritized care, operational factors can lead to prolonged median waiting times, particularly for Level 3 patients, who may wait 95 to 105 minutes for the start of clinical intervention, significantly exceeding the 60-minute benchmark. This "wait time gap" increases the risk of dynamic deterioration—a stable Level 4 or 5 patient potentially collapsing into a Level 2 while waiting—underscoring the tension between system ideal and resource limitation.

Advanced Assessment: Subjective Modifiers and Nuanced Risk Stratification

Modern triage recognizes that acuity scoring must incorporate subjective elements that reflect potential underlying risk, such as pain and psychological status, integrating them with objective physiological data.

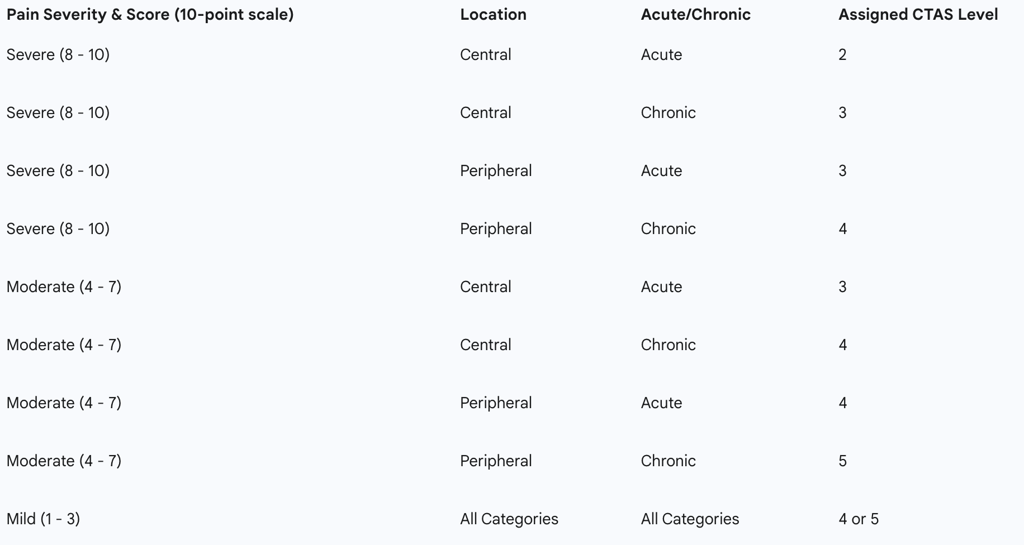

4.1. Pain Assessment as a Triage Modifier

Pain assessment is a mandatory element of triage, often utilizing a 10-point Likert scale to gauge severity. Systems like CTAS use pain severity, location, and chronicity as "First Order Modifiers" to refine the triage score. This approach forces the triage professional to integrate early differential diagnosis into the prioritization process.

The critical differentiation lies in the origin of the pain:

Central Pain: Pain originating within a body cavity or organ (e.g., chest, abdomen, pelvis). This location is statistically associated with a higher risk of underlying life- or limb-threatening conditions.

Peripheral Pain: Pain originating in the skin, soft tissues, or axial skeleton. Dangerous diagnoses are considered less likely to be missed in this context.

Furthermore, acute pain (new onset) is triaged higher than chronic pain (recognized recurring syndrome). However, any change in the pattern or severity of chronic pain must be treated as acute pain. By standardizing the evaluation of pain based on these clinical characteristics, the triage system elevates the process from simple symptom documentation to active clinical risk stratification, ensuring that symptoms potentially masking major pathology receive appropriate urgent prioritization. For example, the presence of severe pain (8–10) that is acute and central immediately results in a CTAS Level 2 assignment.

Table 3: CTAS Pain Severity Triage Scoring Matrix (First Order Modifier)

Special Status Presentation and Psychological Modifiers

Specific clinical presentations serve as high-acuity modifiers. An altered level of consciousness (LOC), defined by a GCS score of 10–13 (loss of orientation, new confusion, or agitation), necessitates a CTAS Level 2 assignment. A patient presenting with a fever accompanied by an altered LOC is automatically assigned Level 2 and is considered high risk for severe sepsis. Unconsciousness or an inability to protect the airway (GCS 3–9) is a Level 1 classification.

Triage protocols also address psychological emergencies. Urgent mental health problems are recognized as Level 3 conditions, requiring intervention within a target time to mitigate risk to the patient or others.

4.3. Recognizing and Managing the Deteriorating Patient (Dynamic Re-Triage)

The triage process is inherently dynamic, acknowledging that a patient's condition can change rapidly. A score assigned at arrival based on a focused assessment is not fixed. Deterioration while awaiting treatment represents a critical breakdown in patient safety, potentially leading to adverse outcomes.

If a patient’s vital signs or symptoms worsen (e.g., increasing pain, new breathing difficulty, or altered mental status), they must be immediately re-assessed by a nurse or clinician. The result of this re-triage may be the assignment of a significantly higher acuity level (e.g., moving from Level 4 to Level 2), which triggers immediate transfer to a treatment area. This mechanism ensures that patients who were initially stable but are now declining are prioritized for immediate life-saving care.

Specialized Triage Protocols for Vulnerable Populations

Triage systems require specialized adjustments when applied to vulnerable populations, specifically pediatric and geriatric patients, whose physiological responses often deviate significantly from standard adult norms.

Pediatric Triage: Adjusting Physiological Norms and Recognizing Subtle Signs

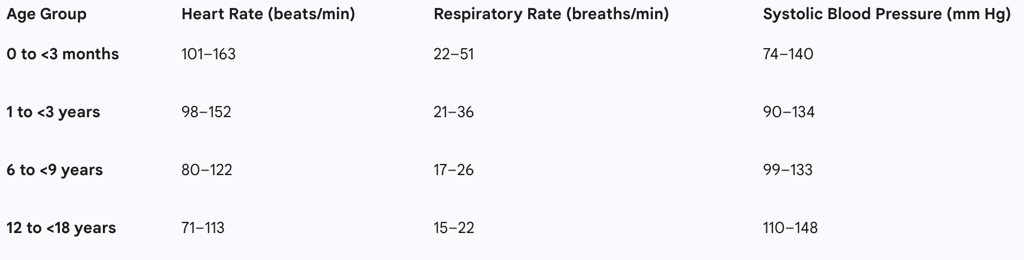

Pediatric triage presents unique challenges, primarily because a child’s vital sign parameters are acutely age-dependent. Applying standard adult metrics to a child would inevitably result in severe under-triage. Therefore, specific physiological cutoff ranges for heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure are necessary to accurately stratify risk across different age groups, from infants to adolescents.

Children possess significant physiological reserves, meaning their vital signs may remain deceptively within 'normal' thresholds even when they are critically ill (compensated shock). Because of this, relying strictly on numerical thresholds risks under-triage. Pediatric triage protocols emphasize rapid observation, noting behavioral cues—for instance, observing that a child who is smiling or crying likely does not have severe respiratory distress or coma. The rapid assessment of the child must also incorporate specific protocols for managing trauma and identifying mechanisms of injury consistent with significant trauma.

Table 2: Pediatric Age-Adjusted Vital Sign Cutoffs for Triage Prioritization (Selected)

Geriatric Triage: The Impact of Co-morbidities and Adjusted Vital Sign Thresholds

Older adults represent a rapidly expanding cohort in the ED, frequently presenting with complex medical conditions, multiple comorbidities, and increased vulnerability due to frailty and cognitive decline. Traditional triage methods often prove inadequate for this population, as they may fail to capture underlying functional deficits.

A critical adaptation in geriatric triage concerns the interpretation of vital signs. Geriatric patients frequently experience compensated shock, sometimes masked by underlying medications such as beta-blockers, which can suppress the typical tachycardic response to critical illness. For geriatric trauma patients, specific protocols dictate that a Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP) of 110 mmHg must be considered the equivalent of 90 mmHg (the traditional shock indicator) for younger adults. This adjustment acknowledges that even modest drops in blood pressure from a patient’s typically hypertensive baseline can indicate severe instability requiring high-acuity prioritization.

To address the limitations of standard measures, specialized tools, such as the Identification of Seniors At Risk (ISAR) tool, are often used to complement existing triage systems (like the Modified Manchester Triage System). These tools capture risk dimensions like functional decline and frailty that are not fully assessed by traditional measures, helping to mitigate the risk of under-triage for this complex demographic. State protocols for trauma must emphasize these special needs to minimize inappropriate transfer or delayed care.

Trauma Triage Protocols

Trauma triage protocols are designed to quickly ascertain the mechanism and severity of injury to ensure transport to the most appropriate level of care, typically a designated trauma center. A core objective of these protocols is to maintain a balance that minimizes both overtriage (wasting specialized trauma center resources on minor injuries) and under-triage (failing to recognize critical trauma, leading to increased morbidity). Protocols, particularly for pediatric trauma, require assessment for serious signs, symptoms, and mechanisms consistent with significant trauma.

Triage in Extreme Conditions: Mass Casualty Incidents (MCI)

Principles of Triage in Limited Resource Environments

In mass casualty incidents (MCIs)—events involving five or more patients where resources are severely overwhelmed—triage shifts from the daily beneficence model to a strictly utilitarian ethical framework. The primary goal is maximizing the aggregate good, meaning resources are allocated to save the greatest number of lives, rather than guaranteeing optimal care for every individual.

MCI triage systems are characterized by their simplicity and speed, designed to be completed in 30 seconds or less per victim, resulting in assignment to one of four color-coded categories:

RED (Immediate): Patients with severe, life-threatening injuries who have a high potential for survival if treated rapidly.

YELLOW (Delayed): Patients with serious injuries that are not immediately life-threatening and whose treatment can be postponed.

GREEN (Minimal): The "Walking wounded," individuals with minor injuries who can move to a designated safe area.

BLACK (Expectant/Deceased): Patients with injuries incompatible with life, or those without spontaneous respiration after basic airway maneuvers.

The START Triage Algorithm (Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment)

The Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (START) system remains the most widely used MCI triage algorithm in the United States. START is predicated on three primary observations, summarized by the mnemonic RPM (Respiration, Perfusion, and Mental Status).

The process begins by requesting all victims who are able to walk to move to a safe collection point, immediately categorizing them as GREEN. For the remaining patients, the rescuer systematically assesses RPM, dedicating no more than one minute per patient to the process.

The RPM assessment criteria are structured to differentiate RED from YELLOW patients:

R (Respiration): If the patient is breathing, the respiratory rate must be less than 30 breaths per minute for delayed treatment.

P (Perfusion): Adequate perfusion is typically indicated by a capillary refill of less than 2 seconds (though modified versions may use the presence of a radial pulse).

M (Mental Status): Mental status is deemed adequate if the patient is able to follow simple commands (Can Do).

The SALT Framework (Sort, Assess, Life-saving Interventions, Treatment/Transport)

The SALT triage framework—standing for Sort, Assess, Life-saving Interventions, Treatment/Transport—was proposed by a CDC-sponsored working group to establish a standardized national guideline for MCI response, designed to be compliant with national standards. Studies suggest SALT results in lower under-triage rates compared to START in simulated scenarios.

The key steps in the SALT algorithm are:

S (Sort): Global sorting of patients (e.g., walking, waving, talking) to prioritize individual assessment.

A (Assess): Rapid individual assessment of critical functions.

L (Life-saving Interventions): This crucial step requires the immediate performance of life-saving interventions (LSI) at the scene, such as controlling major hemorrhage using tourniquets or direct pressure, and opening the airway through positioning or basic maneuvers.

T (Treatment/Transport): Final categorization and transport priority determination.

The integration of the "L" step represents a significant operational evolution, effectively decentralizing immediate critical care. By formally mandating and standardizing the immediate application of life support (LSI) at the point of injury, the SALT framework optimizes outcomes in high-volume disaster settings by beginning critical treatment before the patient is moved or definitively triaged.

Operational Efficiency and the Ethical Landscape of Triage

Triage as a Tool for Optimizing Patient Flow and Resource Allocation

Triage is the cornerstone of emergency room operations, extending its function far beyond clinical assessment into systems management. Efficient triage practices are vital for streamlining operations, optimizing patient flow, and minimizing wait times, thereby enhancing overall patient outcomes.

The judicious allocation of resources is a central responsibility of triage. By clearly identifying the urgency level, triage directs limited resources—such as medical personnel, diagnostic equipment, and specific treatment modalities—toward patients with the most acute needs. Effective resource management not only enhances efficiency but also contributes to cost savings by avoiding unnecessary expenses associated with delayed or inadequate treatment. Furthermore, operational strategies like implementing doctor triage models, rapid assessment zones, and co-locating primary care clinicians within the ED have been proven effective in further improving patient flow.

Challenges to Efficient Triage and Systemic Limitations

Despite the sophistication of modern triage algorithms, multiple challenges impede their optimal function. The most significant external threat is ED overcrowding, which leads to stagnant patient flow, extended triage times, and delays in critical interventions, thereby actively threatening patient safety.

Internally, triage is hindered by systemic limitations. Existing triage systems often demonstrate a lack of universal sensitivity and specificity, making it difficult to establish a single algorithm that applies appropriately to all complex situations. Workflow challenges faced by triage nurses include managing excessive documentation loads (e.g., entering extensive medication lists) and addressing disruptive behavior or demands from family members who are waiting, all of which consume precious time needed for rapid sorting.

Ethical Underpinnings: Balancing Utilitarianism, Beneficence, and Justice

The very necessity of triage arises from the "unhappy truth that, when vital resources are limited," choices must be made regarding prioritization. The ethical framework of triage involves navigating three core concepts: utilitarianism, which seeks the greatest good for the greatest number; beneficence, the obligation to act in the best interest of the individual patient; and justice, the fair and equitable distribution of resources.

Triage forces a moral choice between the principle of "first-come, first-served" and prioritizing the collective need based on medical necessity. When implementing new clinical or administrative protocols, such as those imposed during an epidemic, triage professionals are encouraged to operate under the ethics of care. This principle requires centering decisions on the patient’s objective needs and expectations at the moment conflicts arise between systemic rules and individual interests, with the underlying premise of maintaining the system while ensuring patient interests are not infringed upon.

The Dilemma of Over-triage versus Under-triage

Inaccurate triage poses a serious clinical risk, directly contributing to increased morbidity and mortality. The two primary forms of error are under-triage and over-triage.

Under-triage occurs when a patient is assigned a lower acuity score than their true clinical condition warrants. This can happen due to passive defensive medical behavior (avoiding high-risk patients) or missing subtle cues, especially in vulnerable populations. Under-triage leads to dangerous delays in care.

Over-triage occurs when a patient is assigned a higher acuity score than necessary. While clinically safer for the individual, widespread over-triage strains limited resources by diverting personnel and equipment to non-critical cases, potentially delaying intervention for genuinely life-threatening Level 1 and 2 patients (a utilitarian consequence).

A significant challenge in maintaining consistency is the moderate level of inter-rater reliability (IRR) among triage professionals. Studies indicate a "fair-to-good agreement," with a Fleiss' kappa coefficient around 0.4. This variability in human clinical judgment means that the triage score, and consequently the patient’s time-to-treatment—a key ED performance metric —can depend heavily on which nurse performs the assessment. This lack of robust consensus presents a substantial systemic weakness, increasing organizational liability and clinical risk.

The Future of Risk Stratification: Technology and Reliability

Assessing Reliability and Validity in Triage Decisions

The issue of moderate reliability requires continuous efforts toward system standardization. The consistency of triage decisions is measured by inter-rater reliability (IRR). Research has shown that triage scores assigned based on paper case scenarios can differ significantly from those assigned in live patient settings, highlighting the contextual influence on clinical decision-making.

To address variability, standardized definitions of accuracy and consistency are needed. Emergency department performance indicator thresholds must be utilized as benchmarks for evaluating national triage consistency, thereby driving necessary improvements in training and adherence to protocols. Furthermore, the general effectiveness and validity of existing systems, such as the MTS, continue to show mixed results when subjected to external review.

The Integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Triage Decision Support

The high-stakes nature of emergency medicine, characterized by time pressure and resource constraints, makes it an ideal domain for the application of advanced technologies. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning models are being actively developed and tested to provide clinical decision support and mitigate human error.

Current applications include models that automatically predict the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) level and assist in identifying critically ill patients, such as for early sepsis detection. These systems operate by analyzing massive data streams—including vital signs, laboratory results, and imaging scans—to recognize complex patterns that may reduce diagnostic delays. AI holds the potential to expedite care and significantly enhance predictive accuracy, especially by standardizing clinical judgment and overcoming the moderate IRR inherent in human-only systems.

Addressing Challenges in AI Deployment: Bias, Explainability, and Human Oversight

The integration of AI, while promising, carries significant risks related to safety, liability, and ethical governance. Major challenges include the risk of algorithmic bias, unreliability (sometimes termed "hallucination"), and a lack of interpretability in complex neural network models. Algorithmic bias, if undetected, could exacerbate issues of distributive justice by unfairly penalizing or prioritizing specific demographic groups.

To foster trust and ensure clinical utility, future AI development must prioritize explainable algorithms (XAI). Transparency regarding how AI models prioritize patients is crucial for ethical deployment. Most importantly, structured override processes must be established to enable rapid human intervention when necessary, ensuring that the algorithmic decision can be adjusted based on clinical context and judgment. The ED staff must retain the authority to override AI-driven triage decisions, thus preventing the delegation of ultimate clinical and legal liability to an automated system. Defining clear lines of responsibility among healthcare providers, policy makers, and AI developers is paramount before widespread implementation.

Recommendations for Standardized Data Collection and Triage System Improvement

Moving forward, improvements to triage reliability and efficacy require a focus on both human training and technological rigor. Rigorous multi-center validation and standardized outcome reporting are prerequisites for scaling AI-based triage systems.

For both human and algorithmic systems, the foundation remains complete and accurate data collection. Efforts must be focused on ensuring accurate documentation of vital signs and chief complaints, particularly in populations where data collection is often incomplete, such as young children. Continuous evaluation of the system’s validity and reliability must guide policy decisions, ensuring that resource optimization and prioritization remain aligned with improving patient outcomes.

Conclusions

Triage serves as the essential clinical and operational backbone of the modern Emergency Department, translating the ethical demands of limited resources into a standardized process for clinical risk stratification. Originating from military necessity, modern triage systems like ESI and CTAS systematically evaluate physiological stability, acuity, and resource consumption to assign one of five urgency levels, thereby determining the maximum acceptable wait time for intervention.

The sophistication of contemporary triage lies in its dynamic methodology: using objective vital sign thresholds (adjusted for age) and structured subjective modifiers (such as the location and chronicity of pain) to proactively identify immediate threats to life. However, the analysis demonstrates that operational challenges—chiefly ED overcrowding and the inherent, moderate variability in human clinical judgment—strain the system, leading to a demonstrable gap between ideal time-to-treatment benchmarks and real-world performance.

The future evolution of triage will likely involve the strategic deployment of Artificial Intelligence to enhance consistency, expedite decision-making, and overcome human factors that contribute to inconsistent inter-rater reliability. This integration, however, must be governed by rigorous ethical frameworks centered on transparency and human oversight, ensuring that AI remains a supportive tool for clinical decision-making, rather than an autonomous decision-maker, thereby safeguarding patient autonomy and clarifying legal accountability in this high-stakes environment.