Analysis of Disaster Triage Protocols: START, JumpSTART, and Mass Casualty Systems

The implementation of specialized triage systems is necessitated by the dynamics of a Mass Casualty Incident (MCI). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines MCIs as major incidents characterized by the quantity, severity, and diversity of patients that rapidly overwhelm local medical resources, preventing the delivery of comprehensive and definitive medical care.

The implementation of specialized triage systems is necessitated by the dynamics of a Mass Casualty Incident (MCI). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines MCIs as major incidents characterized by the quantity, severity, and diversity of patients that rapidly overwhelm local medical resources, preventing the delivery of comprehensive and definitive medical care.1 Given the increasing frequency of such events across all socioeconomic backgrounds, robust preparedness and defined pre-hospital triage protocols are essential for optimizing resource initiation and saving lives.1

The Utilitarian Mandate in Resource-Constrained Environments

The fundamental ethical constraint governing MCI triage is the utilitarian principle: protocols are implemented to offer the greatest good to the greatest amount of people when healthcare resources are severely limited or strained.1 This mandate represents a profound deviation from standard, patient-centric medical protocols. Under normal circumstances, pre-hospital care involves aggressive stabilization and treatment. Conversely, during primary field triage, treatment is deliberately minimal.1

This ethical-operational divergence highlights a crucial concept: primary field triage protocols, such as Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (START), function primarily as logistical sorting algorithms rather than initial definitive treatment procedures. The operational goal is to achieve rapid assessment and movement of patients away from the incident scene toward designated collection points, where more comprehensive care resources can be allocated.

B. Dynamic Process and Logistical Distinctions

Triaging during an MCI is inherently a dynamic and fluid process that requires continuous reassessment. Patients may initially be assigned one category but must be re-categorized due to changes in their clinical status, often requiring triage tags designed with fold-over tabs to easily switch designations.1 Emphasis is consistently placed on the speed of assessment and movement rather than extensive stabilization.1

It is imperative to recognize that primary triage systems are designed solely for prioritizing and segregating patients based on immediate physiological status; they are not intended to determine detailed resource allocation strategies.1 Complex decisions regarding specialized equipment deployment, destination hospital assignments, or secondary treatment logistics are functions of incident command and transport management, which occur subsequent to the initial categorization process. The fluidity of patient status demands integration with external logistical structures, requiring constant reassessment as patients move through the continuum of care.1

The Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (START) System

The Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (START) system remains a foundational and widely utilized field triage system in developed countries, notably the United States.2 START is celebrated for its swift application, typically requiring less than 60 seconds per patient, relying on rapid physiological assessment to assign one of four injury severity classifications.

A. Core Categories and Initial Ambulation Sorting

START utilizes a four-tier classification system designated by color and description 1:

GREEN (Walking Wounded/Minor): Minor injuries.

YELLOW (Delayed): Serious but not immediately life-threatening injuries.

RED (Immediate): Severe injuries with a high potential for survival if treated immediately.

BLACK (Deceased/Expectant): Injuries incompatible with life or without spontaneous respiration.

The process begins with a crucial logistical maneuver: the triage officer instructs all patients who can walk to move to a designated collection point.3 These ambulatory patients are immediately triaged as GREEN.1 This action effectively removes the least resource-intensive patients from the assessment queue, allowing responders to focus finite resources on non-ambulatory, potentially critical patients.3

Sequential RPM Assessment Criteria

The non-ambulatory patients are assessed sequentially using three key physiological criteria, summarized by the mnemonic "RPM: 30-2-can do".1

Respirations (R)

The initial assessment determines the presence of spontaneous breathing.

If the patient is apneic (not breathing), the airway is opened (e.g., using head tilt/chin lift).3

If the patient remains apneic after airway positioning, the patient is tagged BLACK (Deceased/expectant).1 These patients should not be moved forward.1

If spontaneous breathing begins after airway positioning, the patient is tagged RED (Immediate).3

If spontaneous breathing is present, the respiratory rate (RR) is assessed.3

If RR is greater than 30 breaths per minute ($>30$), the patient is tagged RED (Immediate).1

If RR is 30 or less ($\leq 30$), the assessment proceeds to Perfusion.

Perfusion (P)

Perfusion is assessed through either capillary refill time (CRT) or the presence of a radial pulse.1

If CRT is greater than 2 seconds ($>2$ sec), or if the radial pulse is absent, the patient is tagged RED (Immediate).1 Bleeding control (often implemented by direct pressure or through the direction of a non-injured bystander) may be attempted.3

If CRT is 2 seconds or less ($\leq 2$ sec) and a radial pulse is present, the assessment proceeds to Mental Status.

3. Mental Status (M)

Mental status is determined by the patient's ability to follow simple commands.

If the patient is unable to follow simple commands, the patient is tagged RED (Immediate).

If the patient is able to follow simple commands, the patient is tagged YELLOW (Delayed).

Limitations of START’s Physiological Constraints

The reliance on rigid, sequential physiological cutoffs in the "RPM: 30-2-can do" formula represents a structural vulnerability in the START system. While designed for speed, this methodology may overlook the profound compensatory mechanisms often exhibited by healthy trauma patients. For example, a young adult suffering significant internal hemorrhage might initially maintain a stable respiratory rate ($\leq 30$) and intact mental status (able to follow commands) while compensating for circulatory collapse. If external factors impede the accurate measurement of perfusion—specifically if Capillary Refill Time (CRT) is used 1—the patient risks being undertriaged as Yellow.

Furthermore, the dependence on CRT for perfusion assessment is problematic. CRT is notoriously unreliable under challenging field conditions, such as cold environments, low ambient light, or even pre-existing shock states.1 If responders solely rely on CRT in these adverse settings, the system's accuracy decreases significantly, potentially resulting in the classification of true immediate patients as delayed. This suggests that the simplicity of START, while facilitating rapid throughput, comes at the cost of diagnostic robustness under non-ideal, real-world MCI conditions.

Specialized Pediatric Triage: The JumpSTART Protocol

Because primary MCI triage relies on physiological measurements 3, and the physiology of children is fundamentally different from that of adults 3, applying adult START criteria to pediatric victims is inappropriate and would lead to high error rates. The JumpSTART Pediatric Triage Algorithm was developed to address these specific needs, originating at the Miami, Florida Children's Hospital in 1995 and subsequently undergoing modification in 2001.4 JumpSTART is currently the most commonly utilized pediatric mass casualty triage algorithm in the United States.

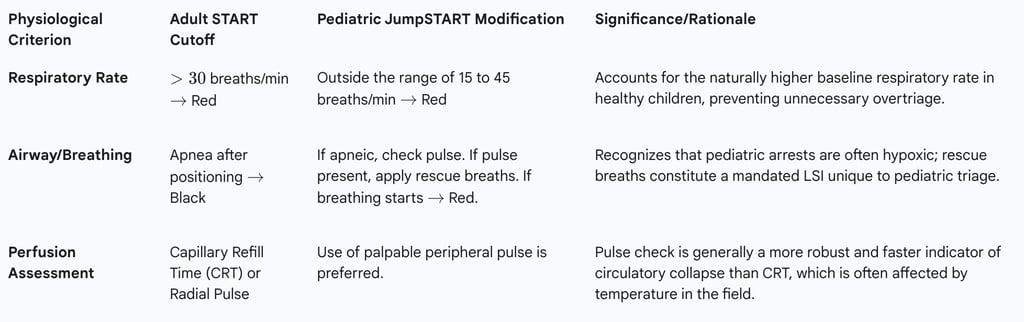

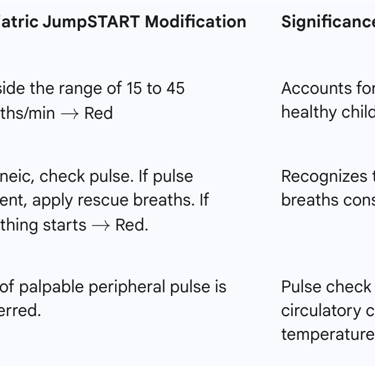

Modifications to Respiratory Assessment

JumpSTART maintains the core structure of START (ambulatory sorting followed by RPM assessment) but utilizes adjusted physiological thresholds suitable for pre-adolescent children (or those under approximately 100 pounds).

The most critical modification involves the respiratory rate (RR) cutoff. Recognizing children’s higher baseline norms, a patient is tagged RED (Immediate) if their spontaneous breathing rate is outside the expected range of 15 to 45 per minute.5 This adjustment prevents the unnecessary overtriage of children who are simply breathing faster than the adult threshold of 30 breaths per minute.

Mandated Lifesaving Intervention: Rescue Breathing

The handling of apnea in JumpSTART represents a critical policy deviation from adult START, introducing a mandatory limited intervention into the primary triage process.6

If a non-ambulatory child is found to be apneic (not spontaneously breathing), the responder attempts to open the airway using conventional positional techniques.6 If breathing is not triggered, the responder proceeds to palpate for a pulse (peripheral preferred).5

If a palpable pulse is present but the patient is still apneic, the provider is mandated to administer up to five rescue breaths.4 If, after rescue breaths, spontaneous breathing resumes, the child is tagged RED (Immediate). This procedure formalizes a basic Lifesaving Intervention (LSI) within the triage algorithm, founded on the recognition that pediatric arrests are frequently respiratory in origin and often reversible with simple ventilation. If no pulse is present, or if breathing is not triggered by the positional techniques or rescue breaths, the patient is tagged BLACK (Deceased/Expectant).6

This policy decision shifts JumpSTART from a pure assessment model to an assessment-and-limited-resuscitation model, effectively serving as a philosophical bridge between the simplicity of START and the more interventionist approach of the SALT protocol.

JumpSTART Pediatric Triage Key Modifications

Training and Validation Concerns

Despite being the most common pediatric triage algorithm in the US, formal scientific review of JumpSTART’s efficacy remains limited. This lack of extensive real-world validation highlights a reliance on training fidelity for system reliability. Effective disaster preparedness programs must ensure that primary responders are rigorously trained in the pediatric-specific respiratory rate cutoffs (15–45) and the critical procedure involving rescue breaths. If providers revert to the adult START criteria, children breathing between 31 and 45 times per minute could be unnecessarily categorized as Immediate (Red), leading to resource strain through overtriage. The effectiveness of the protocol is thus highly dependent on specialized training to avoid mistakes in medical judgment during the emotional challenge of an MCI involving children.

Comprehensive Triage Protocols: The SALT System

The Sort, Assess, Lifesaving Interventions, Treatment/Transport (SALT) system represents a significant evolution in primary field triage, formulated by a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) work group and endorsed by the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP). The development of SALT was driven by the recognized need for a national standard, as disasters frequently cross jurisdictional boundaries involving responders from multiple agencies.

The Five-Step SALT Process

The SALT system mandates a sequential five-step process :

STEP 1: SORT (Global Prioritization)

Unlike START, which immediately isolates the walking wounded, SALT begins with a global sorting designed to prioritize patients for individual assessment, not final triage classification.

Minimal Priority: Patients who can walk are asked to move to a designated area and receive the lowest priority for individual assessment.

Second Priority: Non-ambulatory patients are observed for purposeful movement or are asked to wave.

First Priority: Patients who are still (do not move) or have obvious life-threatening conditions are assessed first, as they represent the highest likelihood of needing immediate lifesaving interventions (LSI).

STEP 2 & 3: ASSESS and LIFESAVING INTERVENTIONS (LSI)

The assessment phase in SALT is uniquely integrated with limited, rapid LSI. These interventions must be performed only if the necessary equipment is immediately available and falls within the responder’s scope of practice. This integration of intervention before final categorization is the hallmark of SALT, aiming to maximize survivability by correcting immediately reversible conditions.

Mandatory LSI include :

Control of major hemorrhage using tourniquets or direct pressure (potentially administered by other patients).

Opening of the airway through positioning or basic airway adjuncts (advanced airway devices are prohibited).

Pediatric consideration: For children, considering and administering two rescue breaths.

Chest decompression (needle decompression).

Administration of autoinjector antidotes (e.g., nerve agent exposure).

The provision of LSI significantly improves the accuracy and clinical utility of the system. By intervening to control massive hemorrhage or open an airway, patients who would have been incorrectly classified as Black or Yellow under START due to an immediately reversible crisis are stabilized, leading to a truer physiological assessment and more accurate final categorization. This interventionist policy is directly responsible for SALT’s superior performance in reducing undertriage rates.

Treatment and/or Transport Categories (The 5-Color System)

SALT utilizes a five-category system, formally introducing the "Expectant" category.

Immediate (Red): Patients who, even after LSI, exhibit critical signs such as respiratory distress, uncontrolled major hemorrhage, absent peripheral pulse, or inability to obey commands.

Expectant (Gray): This category is assigned to immediate patients whose injuries are deemed incompatible with life given the current resources available.

Delayed (Yellow): Patients whose injuries are serious but not immediately life-threatening and who do not fall into any other category.

Minimal (Green): Patients with mild, self-limited injuries who can tolerate a delay in care.

Dead (Black): Patients who remain apneic and pulseless even after LSI attempts have been made.

STEP 4 & 5: TREATMENT AND/OR TRANSPORT

Transport priority is clearly established: Immediate (Red) patients are moved first, followed by Delayed (Yellow) patients, and finally Minimal (Green) patients. Expectant (Gray) patients receive treatment and/or transport only when resources permit, typically palliative care or movement after all higher priority patients have been managed. This classification provides ethical transparency and logistical clarity, ensuring that critical, finite assets are formally directed toward patients with the highest probability of survival. The entire process remains dynamic, requiring reassessment of all lower-priority patients (Expectant, Delayed, and Minimal) as soon as possible to account for clinical decompensation or improvement.

Comparative Efficacy, Validation, and System Integration

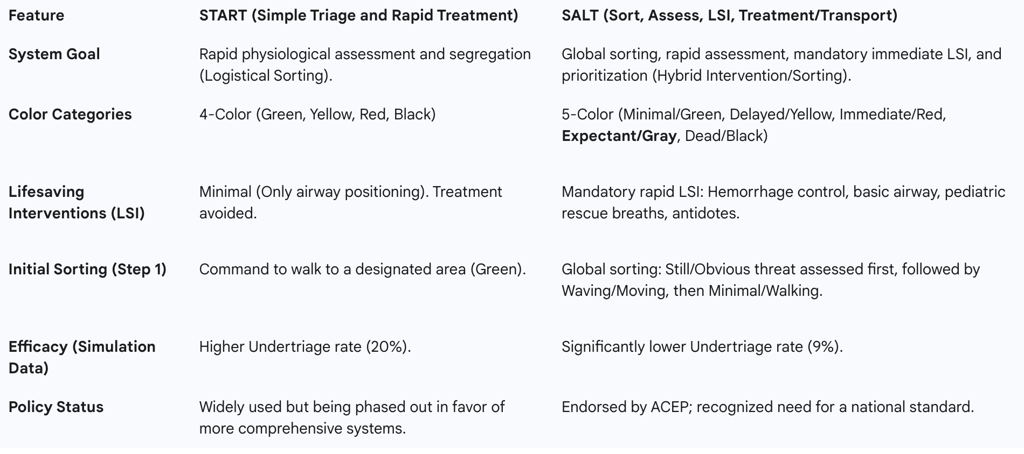

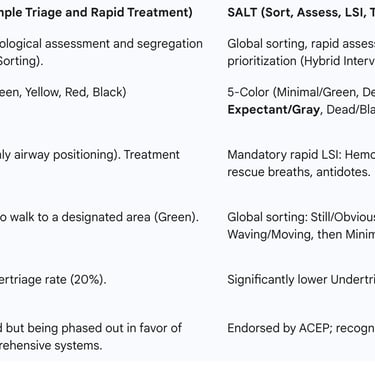

The adoption of mass casualty systems is increasingly governed by validated performance metrics, revealing significant differences between the foundational START protocol and the evolution represented by SALT.

START versus SALT: Performance Metrics

Data derived from field exercises and simulations comparing the efficacy of START and SALT suggest superior classification accuracy for the SALT system.

Undertriage: Undertriage is the classification of an Immediate (Red) patient into a lower priority category (Yellow or Green), a critical error directly linked to preventable mortality. Simulation results demonstrated that SALT had a significantly lower undertriage rate (9%) compared to START (20%).

Overtriage: Overtriage (classifying a Delayed patient as Immediate) strains hospital resources but is generally considered acceptable in MCI protocols. Studies found no significant differences in overtriage rates between the two systems.

The pronounced difference in undertriage rates confirms that SALT is a more accurate triage method than START, particularly in classifying patients into the critical Immediate and Delayed categories. This performance advantage is attributed directly to the required implementation of rapid Lifesaving Interventions in the SALT protocol, which prevents the misclassification of patients whose critical states are immediately reversible.

Comparison of START and SALT Triage Systems

Validation Challenges and the Need for Standardization

A major limitation spanning START, SALT, and other international systems like the Triage Sieve (TS) and Sacco Triage Method (STM) is the reliance on simulated tests for validation. The fidelity and reliability of these triage systems in the unpredictable, high-stress conditions of a real MCI remain a concern, demanding further validation studies outside of simulation environments. Furthermore, due to the diversity of triage tools used globally, international cooperation and standardization efforts are crucial for optimizing responses that cross jurisdictional boundaries.

The documented difference in accuracy between START and SALT has begun to drive a noticeable shift in emergency medical policy. The data-driven preference for SALT, which sacrifices some of START’s simplicity for increased accuracy through LSI, reflects a policy trend toward adopting protocols that minimize preventable mortality, even if they introduce greater operational complexity (e.g., the 5-color system and mandatory interventions).

Integration with Secondary Hospital Triage

Disaster preparedness requires seamless continuity of care, necessitating the linkage of primary field triage systems (like START or SALT) with secondary, hospital-based triage. Once patients arrive at a medical facility, the widely accepted standard for prioritizing care and managing patient flow in the Emergency Department (ED) is the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) algorithm. ESI is utilized by approximately 94% of all US hospitals.

The successful transition of patients from field to hospital is dependent on robust logistical tracking and documentation systems. Triage tags must serve as comprehensive patient transfer documentation tools, incorporating redundancy (electronic or printed) in case of system failure. The required minimum data collected often includes :

Demographic information (Name, Age, Gender).

Triage data (Initial, Secondary, and Hospital time; Chief Complaint).

Vital signs (Time, Pulse, B/P, Respirations, Level of Consciousness).

Treatment records (Time, initials of provider, and comments).

Barcodes or QR codes for tracking and patient identification.

Triage tags must clearly identify the primary triage outcome, including the standard four START colors (Green, Yellow, Red, Black) and, if the 5-color system is utilized, the Gray (Expectant) designation. Critically, the tags must also integrate hazard management documentation, requiring sections to record primary and secondary (final) Hazmat decontamination status, including circling the relevant CBRNE letters to document the nature of contamination. This requirement formalizes the integration of clinical triage with chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and high-yield explosive (CBRNE) response policy, emphasizing that modern disaster triage is a multidisciplinary logistical challenge.

Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

The analysis of disaster triage protocols reveals a continuous evolution from simple logistical sorting (START) toward hybrid systems incorporating limited, high-impact intervention (SALT and JumpSTART).

The START system provides a vital, rapid sorting mechanism, but its strict physiological cutoffs and minimal intervention policy contribute to a relatively high rate of undertriage in complex scenarios. The JumpSTART protocol successfully adapts triage to pediatric physiology by adjusting respiratory rate ranges and, most critically, mandating basic Lifesaving Interventions (LSI) in the form of rescue breaths to address reversible respiratory arrest in children.

The SALT system represents the current policy frontier, endorsed for its comprehensive approach. The inclusion of mandatory LSI—particularly hemorrhage control and basic airway management—before final categorization leads to significantly improved accuracy and a reduced incidence of preventable death compared to START. The explicit addition of the Expectant (Gray) category ensures clear ethical boundaries and optimized resource allocation by diverting limited assets away from patients with injuries deemed incompatible with survival under constrained circumstances.

Policy Recommendations

Standardization on Intervention-Inclusive Protocols: Based on documented efficacy and lower undertriage rates, organizations should prioritize the standardization of field triage protocols toward the SALT system (5-color categorization) for adults, and JumpSTART for pediatric patients. This shift moves the focus from pure speed to optimized accuracy.

Rigor in Specialized Training: Training programs must emphasize the implementation of LSI, ensuring proficiency in major hemorrhage control (tourniquet application) under extreme duress, and precise application of the specialized physiological cutoffs specific to the JumpSTART algorithm (the 15-45 respiratory rate range).

Mandatory Data and Logistics Integration: All licensed agencies should utilize triage documentation systems (electronic or printed) that provide redundancy and ensure seamless data transfer of field assessments (initial triage time, secondary triage time, vital signs, and color category) to the receiving hospital for integration with the Emergency Severity Index (ESI).

Hazmat-Medical Protocol Linkage: Triage documentation must explicitly capture and track decontamination status (primary and secondary), confirming that responders are trained to manage both medical triage and immediate hazardous materials concerns simultaneously.

Pursuit of Real-World Validation: Policymakers and research consortia must prioritize real-world validation studies beyond simulations to confirm the reliability, sensitivity, and specificity of current triage tools in actual MCI environments.