An Expert Analysis of Indian State-Level Triage Systems

The implementation of functional triage systems within Indian hospitals is underpinned by foundational national guidelines established by the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA). These guidelines require all healthcare facilities to adopt a comprehensive Hospital Incident Response System (HIRS) manual.

The implementation of functional triage systems within Indian hospitals is underpinned by foundational national guidelines established by the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA). These guidelines require all healthcare facilities to adopt a comprehensive Hospital Incident Response System (HIRS) manual. The HIRS is crucial not only for managing mass casualty incidents (MCIs) but also for structuring routine high-volume emergency operations.

The HIRS framework mandates several core components designed to ensure organizational resilience during emergencies. These components include a clearly defined Command Structure, often presented as an organizational tree detailing positions, hierarchy, and specific Job Action Sheets for personnel. Furthermore, the system must employ a Modular Organization, allowing the emergency response structure to be flexibly expanded or contracted based on the incident's nature and scale. Response planning is formalized through Consolidated Action Plans, which integrate objectives, strategies, and tactical activities from all participating hospital departments. A paramount principle within this organizational approach is the maintenance of a Manageable Span of Control, which limits the responsibility of each individual supervisor to prevent organizational failure during high-stress operations.

Integrating Administrative Structure with Clinical Acuity

While the NDMA framework provides a mandatory administrative scaffolding for incident response, its focus is primarily on the command structure and resource deployment strategy. Triage, however, is fundamentally a clinical assessment designed to allocate scarce resources effectively in environments where demand often exceeds supply, which is a common characteristic of health systems in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

The success of a national mandate depends critically on the seamless integration between this robust administrative structure (HIRS) and the specific, clinically validated triage algorithm implemented at the state or institutional level. If a hospital successfully establishes a functional HIRS but staff members lack the requisite skills and knowledge for effective clinical triage , then patients will inevitably be miscategorized, leading to poor outcomes despite sound structural organization. Conversely, a perfect clinical protocol cannot prevent system overload if the underlying administrative framework lacks the modular capacity to handle surge events or maintain a manageable span of control during a major incident. Therefore, effective state implementations must demonstrate deliberate strategies to bridge these administrative and clinical domains, ensuring that clinical acuity accurately drives resource allocation within the established command structure.

The Academic Standard: All India Institute of Medical Sciences Triage Protocol (ATP) and International Congruence

Structure and Color-Coding of ATP

The All India Institute of Medical Sciences Triage Protocol (ATP) serves as a vital academic and clinical benchmark for emergency prioritization, particularly in high-volume tertiary care centers within the country's capital, New Delhi. The ATP utilizes a three-level, color-coded system for routine emergency care: Red, Yellow, and Green. This protocol has undergone rigorous prospective validation in academic settings, confirming its utility in prioritizing patient care based on severity.

Comparative Analysis with Global Triage Scales (5-Level Systems)

To understand the operational intensity of the ATP, it is necessary to compare its categories against internationally recognized five-level triage systems, such as the Emergency Severity Index (ESI), the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS), the Manchester Triage System (MTS), and the Australasian Triage Scale (ATS).

The comparison reveals that the ATP's Red category is exceptionally broad, encompassing conditions that span a wide acuity range in international contexts. Specifically, the ATP "Red" partially matches ESI levels 1, 2, and 3; CTAS levels I, II, and III; MTS levels 1 and 2; and ATS levels 1, 2, and 3. These international classifications range from "Immediately life-threatening" (ESI 1) to "Potentially life-threatening or situational urgency" (ATS 3). The ATP "Yellow" cadre, representing moderately serious conditions, aligns with ESI 3 and 4, CTAS IV, MTS 3, and ATS 4, covering potentially serious or urgent cases. Finally, the ATP "Green" category corresponds to the least urgent or non-urgent cases, matching ESI 5, MTS 4, and category 5 of the other international systems.

This breadth in the Red category, encompassing levels 1 through 3 of 5-level scales, implies significant institutional pressure and a potential strategy to minimize catastrophic undertriage in high-volume, resource-constrained environments. By assigning moderately severe but time-critical patients (equivalent to ESI 3) to the Red zone, the ED increases the overall workload and acuity of the most critical area. Consequently, emergency physicians frequently employ re-triage mechanisms to effectively decongest the Red and Yellow zones and manage patient flow. For Yellow category patients in a tertiary academic setting, the average waiting time before assessment in the treatment area can be approximately 150 minutes. This protracted waiting time for urgent patients underscores the need for continuous, mandated re-evaluation of patient status to prevent deterioration, validating the necessity for policies requiring periodic re-triage in all patient care areas.

The application of ATP, being an academic, in-hospital protocol validated in a tertiary setting , must also be distinguished from pre-hospital or disaster triage systems. Field protocols, such as Simple Triage And Rapid Treatment (START) and many EMS protocols, utilize four color codes including Black (Deceased/Expired) to prioritize the living. This divergence necessitates specific training to manage the clinical and administrative handover when patients transition from the 4-level field triage to the 3-level in-hospital ATP.

Case Study: State-Level Institutional Triage Implementation (Kerala Model)

Policy Mandate and Structured Implementation

Kerala has implemented a sophisticated, statewide triage system enforced through government orders, extending the protocol across all tiers of public healthcare institutions, including General Hospitals, District Hospitals, Taluk Hospitals, and Community Health Centres. This mandate operationalizes the triage process through strict requirements concerning personnel and infrastructure.

Every Emergency Department is required to maintain a dedicated Triage Desk and a defined Triage Area. Crucially, the policy mandates that the Triage Desk must be manned by a Staff Nurse specifically trained in triage procedures, under the supervision of the Nursing Superintendent or Head Nurse. This directive represents a direct response to common organizational shortcomings identified nationwide, where lack of skills, undefined roles, and the absence of a dedicated triage nurse often constitute major systemic bottlenecks in emergency care delivery.

The operational procedure is standardized: the triage nurse must perform a systematic triage of all incoming patients, categorize them appropriately, and guide them to their respective care areas. Documentation is mandatory, with all triage details required to be recorded in a prescribed Triage Format , and the Doctor on Duty must be immediately notified of the patient’s category. For non-urgent cases, Green category patients are managed in the waiting area via a token number and queue system, standardizing the workflow for low-acuity patients.

Patient Flow and Institutional Accountability

The Kerala model recognizes that effective triage requires not just initial assessment, but sustained dynamic monitoring and enforced patient flow management. To ensure continuous monitoring, the policy explicitly mandates that Staff Nurses, Interns, and Residents posted in the Red, Yellow, and Green patient care areas must perform periodic re-triage to identify deteriorating patients or those whose acuity level has changed.

The most significant policy mechanism introduced to guarantee flow and prevent hospital congestion is the 24-Hour Rule. The Doctor on Duty is strictly required to ensure that no patient is retained in the Emergency Department for more than 24 hours after reporting to the Triage Desk. This rule serves as a powerful regulatory tool to compel timely decisions regarding referral to higher centers, admission to inpatient wards, or discharge following initial stabilization.

The policy enforcement of patient flow metrics, such as the 24-hour limit, is a highly sophisticated approach to quality improvement. It acknowledges that systemic failure often occurs not at the point of initial assessment, but downstream due to ED boarding and congestion. By setting a hard limit on ED stay, the government effectively externalizes the pressure of patient backlog to the entire hospital system, ensuring that the initial triage prioritization (Red, Yellow, Green) translates into timely definitive care. This regulatory response provides a robust mechanism to address the systemic failures identified in quality improvement studies across India, which demonstrate that bottlenecks like undefined roles and delays hinder timely care delivery. Furthermore, a structured and controlled patient flow, driven by effective triage protocols, inherently improves the overall security environment within healthcare institutions, addressing concerns related to staff safety.

Specialized and Contextual Triage Systems

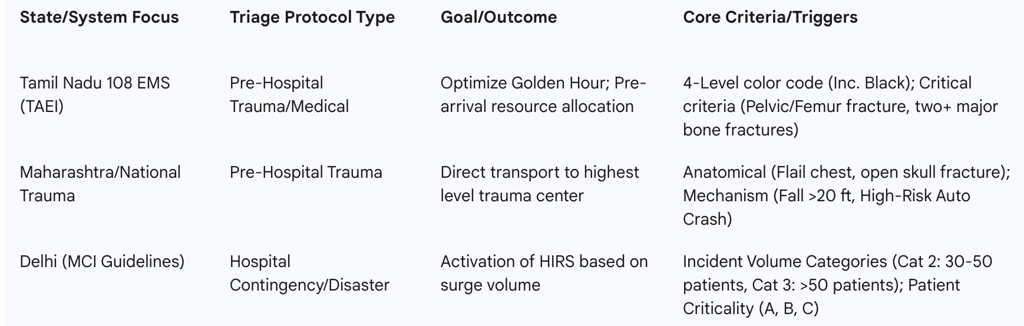

A. Pre-Hospital and Trauma Triage: The Tamil Nadu (TAEI) and Maharashtra Models

Pre-hospital triage in India is increasingly shifting towards evidence-based algorithms designed to ensure the swift transport of injured patients to the appropriate level of definitive care, thus maximizing survival within the "Golden Hour."

Tamil Nadu EMS and TAEI: The Tamil Nadu Accident and Emergency Care Initiative (TAEI) operates through the 108 Emergency Medical Services (EMS) system and has prioritized pre-arrival resource preparation. Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs) use a pre-notification service to alert the receiving hospital, such as the Coimbatore Medical College Hospital (CMCH), about the patient’s condition before arrival. This systematic pre-arrival intimation allows the hospital staff to prepare the appropriate teams and resources for time-critical conditions, including trauma, stroke, ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI), and pediatric resuscitation emergencies.

The 108 EMS system generally employs the four-level color-coded triage system common in field and disaster settings: Red (Immediate), Yellow (Urgent), Green (Non-Urgent), and crucially, Black (Dead/Deceased). This inclusion of the Black category confirms the system's function as a prioritization tool aimed at maximizing survival by focusing resources on patients with the greatest chance of a positive outcome.

Field EMTs apply critical anatomical and physiological criteria equivalent to Red Triage for immediate transport. These criteria include specific high-acuity trauma patterns such as head injury combined with vomiting or convulsions, two or more major bone fractures, open fractures, pelvic injury or fracture, and penetrating wounds in the pelvis or femur regions.

Maharashtra/National Trauma Guidelines: Protocols employed in the trauma systems, often referencing national guidelines, utilize specific criteria to mandate preferential transport to the highest level of trauma center available. These systems rely on global standards based on anatomical injury, mechanism of injury, and specific patient considerations.

Anatomical triggers for immediate trauma center transport include all penetrating injuries to the head, neck, torso, or extremities proximal to the elbow or knee; flail chest; two or more proximal long-bone fractures; crushed, degloved, or mangled extremities; and open or depressed skull fractures. Mechanism-of-injury criteria include high-risk auto crashes (e.g., compartment intrusion greater than 12 inches, partial or complete ejection), severe falls (greater than 20 feet for adults), and high-speed motorcycle crashes. Furthermore, the protocols emphasize special patient considerations, noting that the risk of injury death increases significantly for older adults (age greater than 55) and that children should be preferentially triaged to pediatric-capable trauma centers.

The reliance on highly specific anatomical and mechanism criteria in state protocols demonstrates a significant maturity in the management of trauma systems. These protocols focus on maximizing the probability of identifying high-severity injuries early, minimizing delayed transfer, and ensuring the correct resource matching—sending the right patient to the right facility immediately. This sophisticated approach, requiring rigorous EMT training in criteria such as specific intrusion depths, is critical for reducing trauma mortality rates.

Table II: Comparative State Implementation of Specialized Triage Protocols

Mass Casualty Incident (MCI) and Contingency Planning (Delhi Model)

Contingency planning for mass casualty events requires a distinct triage and capacity management approach. Guidelines often utilized in major metropolitan areas, such as those related to Delhi’s hospital preparedness, define disaster severity and patient criticality separately.

The system uses a patient classification (A, B, C) to define required intervention: Category A (Critical, requiring immediate resuscitation, with about 10% possibly beyond salvage), Category B (Serious but not life-threatening, such as less severe trauma or fractures without major blood loss), and Category C (Walking Wounded, requiring minor procedures).5

Simultaneously, the guidelines classify the surge event itself based on patient volume: Category 2 (thirty to fifty patients from a single incident) and Category 3 (more than fifty patients) for a 1000-bedded tertiary facility.5 This volume classification is designed to trigger specific levels of the HIRS response and resource mobilization. This dual classification ensures that the operational planning is based on the projected demand, allowing the hospital administration to calculate its internal treatment capacity quickly based on previous experiences.5

C. Scaling Triage Beyond the Emergency Department

The challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the necessity of highly flexible and decentralized triage strategies. During the second wave surge in Chennai, effective management of a rapid rise in cases was achieved by scaling triage out of the formal hospital setting.17

A successful scalable triage strategy involved establishing standalone triage centers outside hospitals during the first wave, capable of catering to up to 2500 patients daily.17 This was supplemented by a home-based triage protocol for low-risk patients (aged $\le 45$ years without comorbidities).17 The process proved highly effective: among nearly 28,000 cases managed in a one-month period, the field teams triaged 55.1% of patients, and 69.1% were advised to self-isolate at home, with only a small fraction (6.2%) requiring hospital admission.17 This model illustrates that modern triage in high-density urban settings must function as a community health intervention to manage population-level demand, rather than merely an ED gatekeeping function, preserving scarce hospital beds for high-acuity patients.

Operationalization, Efficacy Assessment, and Systemic Bottlenecks

A. Root Cause Analysis of Implementation Failure

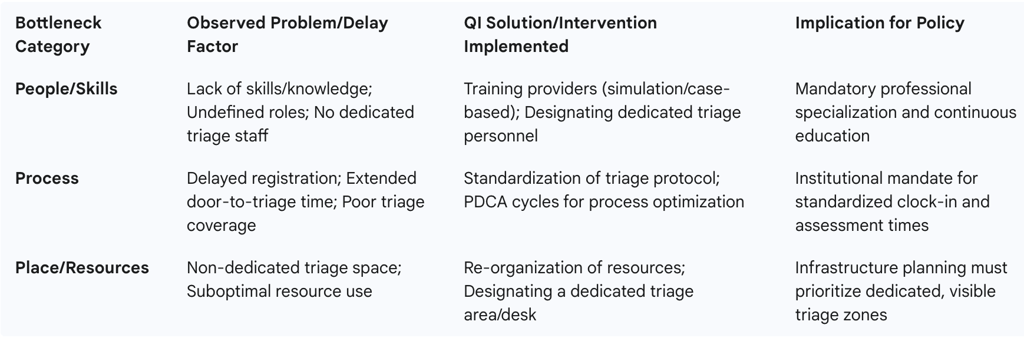

The primary obstacles to implementing effective triage protocols are generally not related to the quality of the clinical model itself (e.g., ATP) but rather the failure in operationalizing these models due to chronic organizational and resource deficits. Quality Improvement (QI) teams, employing robust methodologies like process maps and cause-and-effect (fishbone) analysis, consistently pinpoint bottlenecks leading to detrimental outcomes such as extended door-to-triage times, poor triage coverage, and low patient satisfaction.4

The critical systemic deficiencies are categorized as follows:

People: Bottlenecks include a widespread lack of skills and knowledge among staff performing triage, coupled with undefined roles and the lack of a dedicated, professional triage nurse.4

Process: Problems manifest as significant delays in patient registration and overall door-to-triage time, often stemming from the absence of a standardized triage protocol.4

Place and Resources: Physical constraints involve the absence of a designated space for triage activities and the suboptimal utilization of existing resources.4

Interventions tested via Plan–Do–Check–Act (PDCA) cycles to address these failures invariably focused on standardization and professionalization. Solutions included implementing standardized triage tools, designating dedicated staff for triage, reorganizing physical resources and space, and crucially, enhancing professional development through training using methods like case-based scenarios and simulation.4 The routine identification of "lack of skills" and "no dedicated nurse" as core issues suggests a fundamental failure in policy and funding to create and sustain professional roles and specialized training curricula prior to protocol rollout, resulting in a systemic disconnect between the intent of the policy and its execution in practice.

B. Contextual Disparities and the Challenge of Undertriage

The geographical and infrastructural variations across India create distinct risk profiles for undertriage (the failure to identify a severely injured patient and transport them to a high-level trauma center). Analysis confirms a significantly higher odds of undertriage among rural patients compared with urban patients.18 This finding highlights a systemic vulnerability in the rural patient pathway.

The specific triage criteria that predict undertriage also vary by context 18:

Rural Patient Predictors: Crush injury, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score $\le 13$, and penetrating injury were the top criteria predicting undertriage in rural settings.18

Urban Patient Predictors: Pelvic fracture, paralysis, and GCS score $\le 13$ were the top predictors in urban settings.18

The variation in injury patterns and associated undertriage risk implies radically different failure points in the system. While GCS $\le 13$ is a universal marker for severe injury, the emphasis on crush and penetrating injuries in rural undertriage suggests delays in extrication, assessment, or transport capabilities for complex, time-sensitive trauma. This is likely due to critical infrastructure limitations, such as distant trauma centers or the absence of advanced transport options, which demand a specialized, context-aware EMS response and training curriculum tailored to the rural environment. The necessary policy response must include targeted investment in rural trauma infrastructure, potentially including air or advanced ground transport, to mitigate these critical delays.

Table III: Systemic Bottlenecks and Quality Improvement Interventions in Indian Triage Systems

Conclusions and Policy Recommendations for National Triage System Harmonization and Sustainability

The landscape of Indian triage systems is characterized by a mature national administrative framework (HIRS) and clinically validated institutional protocols (ATP), but with diverse state implementations and significant systemic barriers in operationalization, particularly related to human capital and infrastructure. Triage effectiveness is critically challenged by the "Broad Red" categorization in high-volume EDs and persistent bottlenecks in personnel management, resource allocation, and specialized care delivery to rural populations.

Mandating a Unified Triage Education and Professionalization Standard

To overcome the pervasive issue of inadequate staff skills and the absence of defined roles, national policy must enforce the creation of a unified, simulation-based training curriculum for all emergency personnel—including ED nurses, interns, residents, and EMS staff. This curriculum must specifically include advanced modules addressing complex trauma criteria (anatomical and mechanism-of-injury based) and specialized risk profiles associated with rural injury patterns (crush injury, penetrating trauma). Furthermore, states must be mandated to institutionalize the role of the dedicated, trained triage nurse, following models such as Kerala’s, to ensure consistent and professional initial assessment.

Integrating Pre-Hospital and In-Hospital Protocols

The transition of care from the pre-hospital setting to the ED often introduces delays and information loss. It is essential to integrate the 4-level color-coded field triage (e.g., 108 EMS) with the 3-level in-hospital protocols (ATP/HIRS). National guidelines should mandate the adoption of pre-arrival notification systems, such as Tamil Nadu’s TAEI initiative , to link field assessment data directly to hospital resource pre-allocation, ensuring that the "Red-to-Red" handover is seamless and immediate. The clinical translation between the field (4-level, including Black) and the ED (3-level) must be formalized in training to eliminate clinical confusion at the point of handover.

Regulatory Enforcement of Patient Flow and Quality Assurance

Triage prioritization is meaningless if patient flow stagnates in the emergency department. Policy must shift focus from solely clinical assessment to rigorous system accountability. Institutions should be mandated to implement point-of-care Quality Improvement methodologies (e.g., fishbone analysis and PDCA cycles) to continuously identify and resolve localized process failures.

Crucially, state-level governments should adopt and enforce quantitative patient flow metrics, such as Kerala’s 24-hour ED retention rule. Enforcing maximum limits on ED length of stay forces institutional commitment to rapid admission, transfer, or discharge, guaranteeing that the initial triage assessment leads to timely definitive care and prevents system-wide congestion.

Targeted Mitigation of Rural Disparities

The documented disparity in undertriage risk, particularly for complex injuries like crush trauma in rural settings , necessitates targeted policy action. Resource investment must prioritize the expansion of trauma system resources, including air medical transport (HEMS) and advanced ground transport capabilities, in rural counties. Triage protocols in these areas must be reinforced with specific training that improves field recognition and immediate diversion for time-critical injuries frequently missed or delayed in rural settings. Furthermore, national preparedness planning must incorporate lessons from the Chennai experience , mandating the preparation of decentralized, scalable triage facilities for rapid deployment during public health crises, preserving high-acuity hospital capacity effectively.